Women's Studies takes a critical(and sometimes withering) lookat the intellectual canon.

THE MOST exciting moments in learning come at its frontiers a question that has never been asked before, or an unstudied area of experience. In the truest spirit of the liberal arts, one such frontier is being explored at Dartmouth in the silence of the library and the exuberance of the classroom: the Women's Studies Program, where students examine the experiences of people who once received scant consideration in academia.

In its decade and a half of growth, this field has extended beyond the study of women. Women's Studies has also turned a skeptical eye on the foundations of that male-defined institution we call academia. Scholars have been pushed to reevaluate the intellectual canon, to examine the dynamics of pedagogy, to break down the boundaries of disciplines, and to dissolve the false wall between academic and personal, between the ivory tower and "real world" experience.

Women's Studies serves as a new lens through which we look at sociaty and even at the way we study society. This scrutiny requires filling in the absences and silences in the material that is traditionally taught and in the canon of classroom texts. "In some sense, Women's Studies is a corrective," says French Professor Marianne Hirsch. "The curriculum had previously been men's studies."

This process of inclusion is not as simple as it sounds; the academy cannot just add a woman and stir, including, say, one woman's name in a syllabus of male authors or historical figures. Such an approach is harmfully naive, according to Religion Professor Nancy Frankenberry, the program's co-chair. She compares this naivete to the College's first admitting female students without making any changes in the institution itself, "as though women could be planted like trees around the Green and everything else would remain the same."

Shortly before the College began the innocent process of admitting women, the first Women's Studies program in the country was founded at San Jose State. Five years later, in 1978, Dartmouth became the first of the previously all-male Ivy League schools to start a program of its own. Its initial course, titled "Women and Society," is still offered at the College under the heading "Sex, Gender and Society."

Although women faculty at Dartmouth had already begun to teach such courses as "Woman and History" and "The Politics and Literature of Marriage," the establishment of the Women's Studies Program allowed professors to form the critical mass needed to ask the new field's most revolutionary questions. For French Professor Colette Gaudin, who was one of the first women to be granted tenure at the College, the program's formation provided "a complete reawakening" that "made me aware of my position here and also in the culture at large. It changed the orientation of my scholarly interests and the way I could write about them."

As with many students involved in the program, Women's Studies has radically changed my life. As an English major, I took traditional literature courses without giving much thought to why most of them excluded female authors. During my sophomore year, however, I had a surprise introduction to the program. I took two literary survey courses, one of them a dreaded prerequisite for my major. The professors in both classes were feminist scholars who had included women authors and feminist literary criticism in their syllabi. I had expected "Medieval Literature" to be dense and inaccessible, but suddenly I was reading the writings of female mystics alongside Chaucer's tales. In "American Poetry" I discovered not only Robert Frost and William Carlos Williams, but Anne Bradstreet, Edna St. Vincent Millay, and my favorite poet of all, Emily Dickinson.

Gradually, I started to consider the implications of reading women writers. In challenging the literary canon I could question the notion of "major" and "minor" fiction, even examine the very definition of literature. Since then, Women's Studies has become an integral part of my academic experience. Recently I completed a thesis that used a feminist reading of literature and history to establish a relationship between Emily Dickinson and her lesser-known female precursors. To some extent most of my academic work, even in my more traditional courses, is involved with Women's Studies. Now I can read Shakespeare and explore the lost voice of Cressida; I can do a deconstructionist reading of the naming of John Milton's Eve.

Many of the female writers I came to know have long been excluded from the cognoscenti's list of "major" authors. This act of rediscovery, of redefining what is worth study, is one of the motivating forces behind Women's Studies. The initial proposal for a program at Dartmouth gave a withering look at traditional scholarship's ignorance of the female experience. "Women's Studies has emerged," the document asserted, "because traditional academic disciplines have failed to take account of, or analyze, or incorporate into their theory and practice the actual experience and role of women." The charter created a mission "to understand fully women's position in history, society and culture" through interdisciplinary study and new theories and methods.

Women's Studies' indictment of traditional scholarship a perspective that arose from women's growing social and political self-consciousnessmade some critics see a lack of "objectivity" in the new field. But what critics might see as a weakness is one of the program's greatest strengths. It has helped to show that all intellectual perspectives can be said to have a political origin although, in academia, they were once so well hidden that we failed to perceive their bias.

While traditionalists contend that Women's Studies seeks to destroy the ivory tower, feminist scholars are proposing that the tower may never have existed at all. "There's always within the academy some kind of illusion that what we do is not political," says History Professor Leo Spitzer wryly "that what we do is outside of the fray. Then Women's Studies becomes a political act and a threat to the nature of academic inquiry. There's a fear of polluting our standard of apolitical objectivity."

Nonetheless, Women's Studies has gained general acceptance within the American university. At Dartmouth, the program has grown steadily in size and scope. A multi-disciplinary group of some 50 professors teaches nine "core courses," along with 25 affiliated courses that are taught within individual departments. Women's Studies is not a department and has no majors or faculty appointments. Instead, the program buys faculty time from the departments. From its office in the basement of Carpenter Hall, two faculty cochairs, Nancy Frankenberry and History Professor Mary Kelley, along with the program's coordinator, Anne Brooks, plan curricula and policies with a steering committee of eight faculty members and two students. Brooks also produces a newsletter and a calendar to publicize College events ranging from lectures to films to exhibits that are of particular interest to Women's Studies faculty and students. The Carpenter Hall office also houses a library and lounge for study and discussion.

Dartmouth students can complete a Women's Studies certificate to supplement their majors by taking six courses, including an introductory course and an upper-level seminar or independent research project (16 students from my class have earned certificates). The introduction to the program, "Sex, Gender and Society," examines concepts of gender that most students take for granted: the relationship between gender and sex, the socialization of masculine and feminine identities, the depiction of both sexes in popular culture, and the differing roles of men and women in such aspects of life as religion, business and education. As feminism itself has begun to do, the course focuses on issues of race and class and their relationship to the concept of gender.

Woolf. In the quest to document women's lives and thoughts, Women's Studies scholars often go beyond traditional literary and historical texts which are largely the work of men and consequently reflect a masculine perspective on the world to whatever means of expression have been available to women. This can mean turning to letters and diaries, anonymous poems wherever information is hiding.

Women's Studies also emphasizes the importance of interdisciplinary and collaborative research. History Profesor Marysa Navarro, who is associate dean of the social sciences, is currently writing an essay with three other women from Canada, California and Massachusetts on the history of the feminist movement in Latin America. Lynn Higgins, associate professor of French, has joined English Professor Brenda Silver to edit a volume of essays on the representation of rape in literature and the arts. Students have also extended the boundaries of disciplines in their academic projects. Nicole Bunting '87 has presented a dramatic monologue of narratives, poems, diary excerpts and songs titled "Women's Perspectives on War and Peace"; and Judith Greenberg '88 has completed an honors thesis that studies the works of writers Virginia Woolf and Colette and the painter Sonja Delaunay.

The program's core courses are often team-taught by professors from different departments who explore women's experiences through a variety of perspectives and contexts. Some of these professors as part of a critique of traditional male teaching styles are altering their own approaches to the classroom. French Professor Carla Freccero wants her students "to see the teacher in the process of being engaged in pedagogy," to question the nature of professorial authority and to recognize the teacher's own subjectivity.

Freccero is even changing the way in which she grades students. "Sometimes I have them write reports on how they would evaluate themselves," she says, "and then I take these into consideration when I decide the grades." Other professors are moving away from standard short-answer exams to essays and term papers in order to emphasize the process of learning rather than the weight of final test scores. Within the classroom, Women's Studies discussions are often organized in a "rotating chair" fashion in which students call on each other.

Such approaches lend an unusual sense of community to the field, which in turn has led to other innovations. The Feminist Inquiry Seminar is one. Originally organized for faculty to present papers to an amicably critical, supportive audience before they addressed seminars and conferences, the seminar now involves more than 50 members who meet once a month to discuss projects, research and issues in the field.

Students have a similar opportunity in the Women's Studies Senior Colloquium, established in 1980 at the initiative of Beth Baron '80. Students share their projects and papers and solicit comments on all stages of research. "Compare that to a thesis defense, where you're almost on trial," says Maura Nolan '88. "This is a sharing, supportive academic experience." The recently introduced Women's Studies Affinity Housing a dormitory suite shared by eight selected Women's Studies students intensifies collective learning by extending the boundaries of the academy from the classroom into students' very lives.

This blending of personal and academic realms is one of the program's defining characteristics. "Women's Studies speaks immediately to the experiences in our lives," says Mary Kelley. This immediacy can have a powerful effect. "I've had students come to me crying, saying, 'Your course has changed my life,' " recalls Lynn Higgins. "I hope students will have a passionate involvement with whatever they study that all classes do this. But Women's Studies does so especially because gender identity is so central to people's whole identity, and to examine it and fiddle with it can be challenging and frustrating."

The questioning of gender identity also affects students' personal lives. Like some (but not all) students in the program, I have found that an increasing political activism has parallelled my involvement in Women's Studies. Since my sophomore year I have participated in discussions, panels and rallies that dealt with women's issues. Now, at the close of my undergraduate education, I am beginning to question what my role should be in improving the situation of women in our society.

Increasing numbers of students are getting involved in this challenge. Last fall 51 of them were enrolled in the program's introductory course half again as many as in 1985. In the past academic year nearly 500 students, or 14 percent of the undergraduates in residence, were enrolled in core or associated courses.

But Women's Studies still suffers from scarce funding, and some departments have yet to develop an affiliated course. "We'd like to see many more women involved in the natural sciences," says Nancy Frankenberry. She adds: "To enrich our curriculum, we need new faculty. Most of our curricular goals are hostage to the hiring policies of departments, and they don't hire with our values and concerns in mind." When the program came up for its eighth-year review part of the formal process of recognizing any new academic program an outside evaluating committee recommended an endowed Women's Studies chair, future consideration of a Women's Studies major, a mandatory gender-issues course, and "more sensitive treatment" of junior women faculty members by the institution. In the eyes of Women's Studies supporters, none of these goals has been met completely.

Finally, there's the question of the future. Will Women's Studies assume the status of a major or a department? Will it eventually dissolve, as women's experiences become incorporated into every course's curriculum? There is debate even within the program. "In the ideal sense," says Leo Spitzer, "Women's Studies will self-destruct and will just become part of the way we study the world." But Marianne Hirsch warns that success could turn to failure—that a "gender studies" could quickly turn back into men's studies, "because it's so deeply ingrained in us that men are primary and their questions are primary."

President of the class of 1988, Karen Avenoso will attend Oxford this fall as Dartmouth's second female Rhodes Scholar.

Susan Jarvis '87's quilt, which adorns the Women's Studies Program office, patches together women's experiences much as the Women'sStudies Program itself does.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

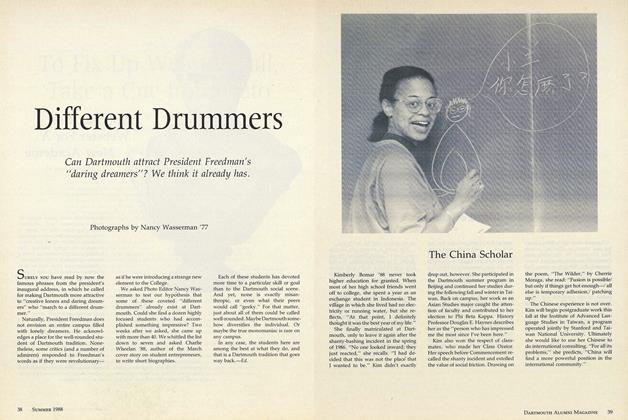

FeatureDifferent Drummers

June 1988 -

Feature

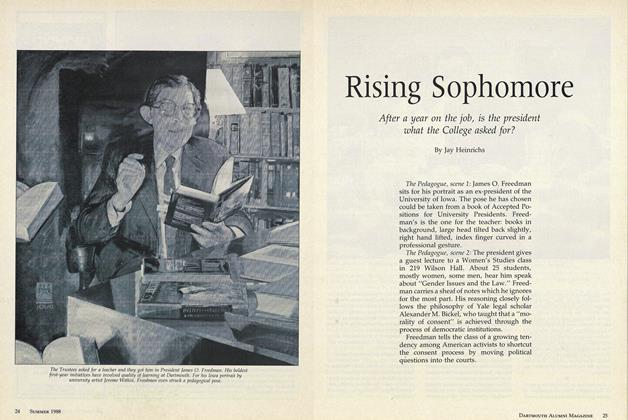

FeatureRising Sophomore

June 1988 By Jay Heinrichs -

Feature

FeatureCommencement '88

June 1988 -

Feature

FeatureTo Fix Up Webster Hall, Take a Cue from Plato

June 1988 By Brad Denny '63 -

Feature

FeatureNext Month: A (Not Altogether) New Look

June 1988 -

Feature

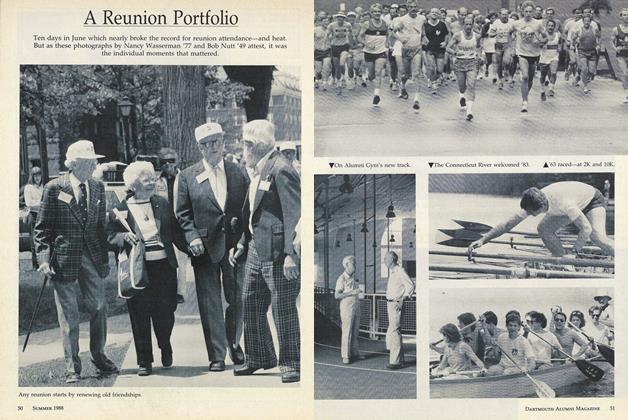

FeatureA Reunion Portfolio

June 1988

Karen Avenoso '88

Features

-

Feature

FeatureThe President on Campus Life

January 1954 -

Feature

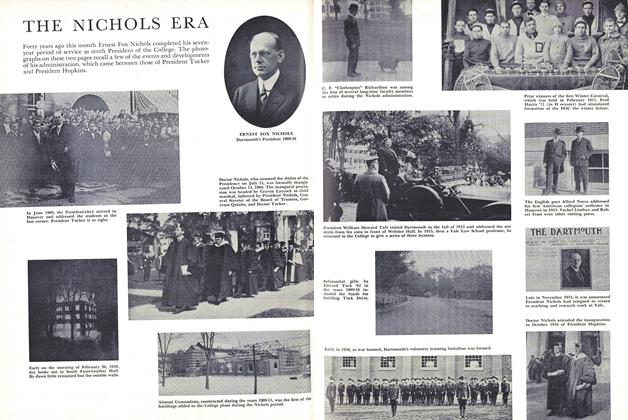

FeatureTHE NICHOLS ERA

June 1956 -

Feature

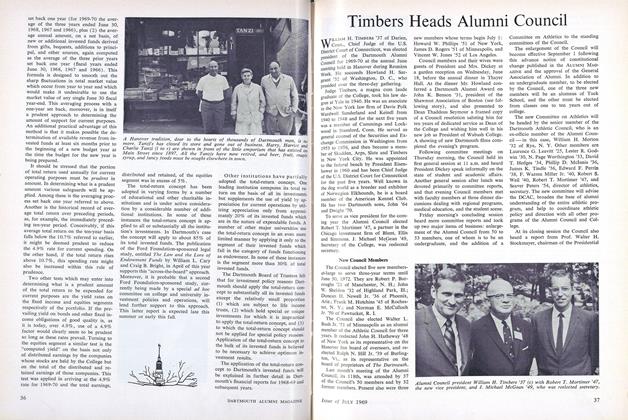

FeatureTimbers Heads Alumni Council

JULY 1969 -

Cover Story

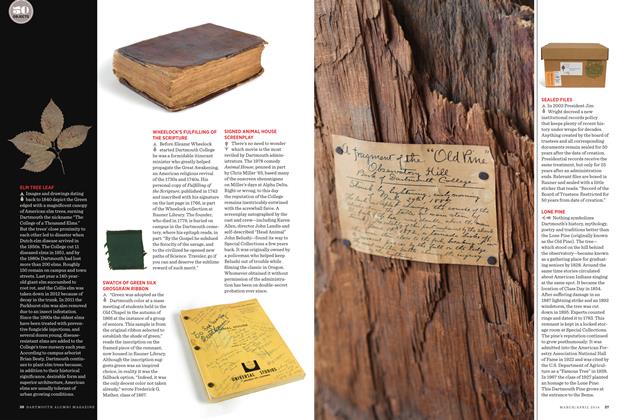

Cover StorySEALED FILES

MARCH | APRIL 2014 -

Feature

FeatureA PORTFOLIO OF THE Dartmouth Cemetery

November 1973 By ADRIAN BOUCHARD -

Feature

FeatureOf Peaceful Men and Violent Ideas

DECEMBER 1968 By DEAN THADDEUS SEYMOUR