Devotees of fiction who have not yet discovered the Japanese novel are missing an opportunity to enlarge their appreciation of what words and images can do to illuminate the human condition. Although modern Japan's novels are at least as diverse as any other country's, many of them share qualities derived from Japan's classical literary tradition: a taste for understatement, an eye for the brilliant image or subtle gesture that speaks more clearly than words, an ear for what is left unsaid.

The spell that novels cast often leads us to forget that they are not mere slices of life but carefully constructed works of art. If we are reading a novel in our own literary tradition, it is particularly easy not to notice the construction, because the pattern it follows meshes so completely with our most basic assumptions about human life and human nature—about personality, plausible motivation, and morality.

When we turn to novels from a sophisticated cultural tradition like Japan's, which has nothing to do with Greek or Roman or Judeo-Christian civilization, we find beyond the surface beauty and exoticism that the basic narrative patterns are often extremely different from what we are used to. The differences force us to stop and examine them and to acknowledge that, just as fiction is a construction created by an author, so too is real life a construction of the culture in which we live.

The readings that follow compose an introduction to a few great writers who have taken the pulse of twentieth-century Japan, from the early throes of its engagement with the civilizations of the West, through the heady prosperity of the 19205, the turbulent and increasingly militarized 19305, the darkest hours of the second world war, and the early years of the postwar economic revival. Novels from these decades reveal that the writers longed for Japan's traditional past and mourned its loss, as they faced the modern world with a mixture of fascination and revulsion.

The writers' mixed feelings emerge in deeply personal images which are often profoundly charged with eroticism. In the novels of Kawabata and Tanizaki in particular, a recurring image is the troubled male protagonist whose self-contradictory impulses are revealed as he is drawn to or repelled by particular women. These women, especially Kawabata's Komako and Tanizaki's Naomi, embody moral and aesthetic choices that the protagonists face.

The choices and solutions presented to the characters are drawn from a specifically Japanese world. For Kawabata's characters, pain and alienation - universal problems of human life - derive from a traditional Japanese view that rationality and self-consciousness exclude human beings from meshing with an otherwise seamless universe. The partial solution Kawabata offers his characters and readers is the possibility of a reconciliation with the universe through the direct experience of beauty unmediated by rationality.

Beyond giving us vividly realized portraits of life in twentieth-century Japan, the novelists have mapped and defined part of the Japanese imagination. For Westerners the view may set in relief our own lives and fiction.

Mary Scott

Novels of fascination and revulsion with modern times.

''I was galvanized by China," says Chinese language instructor Mary Scott, a multi-lingual scholar who travelled to the Far East after graduating from Radcliffe in 1974. "It was still going through the Cultural Revolution and people were under terrible stress," she recalls. "It was so different from anything I'd ever experienced before that I couldn't bear to let go of it." Scott's tenacious curiosity seems to be contagious. After she taught a course on modern Japanese literature last spring, she received letters throughout the summer from students commenting on the books. A language buff all her life, Scott studied Chinese during her senior year at Radcliffe. Chinese intrigued her because it was a radical change from the Romance languages she had taught herself or learned in school in Philadelphia, and because it has a vast literary tradition. "I'm interested in etymology, in how language evolves, and how people's thoughts take shape in language," she explains. During graduate studies at Harvard and Princeton she plunged into Chinese. "The beauty of the literature motivated me to learn the language," she says. Along the way she also studied Japanese. After two long stays in Taiwan and a year at Beijing Normal University, Scott married Chris Connery, a fellow graduate student in Chinese. The two began an academic partnership that led them to the University of Puget Sound and to a joint appointment teaching Chinese at Dartmouth. Coincidentally, this was not Scott's first connection with the College; Dartmouth claims several of her relatives, including her father, William Scott III '51, brother William Scott '81, and sister Caroline Scott '78. Karen Endicott Editor's note: Syllabus marks Scott's farewell to Dartmouth. She and Conneryrecently moved to Stockton, California, where Connery is heading the Chineselanguage program at the University of the Pacific. Scott is taking time off fromteaching to write, study, and enjoy their ten-month-old son.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

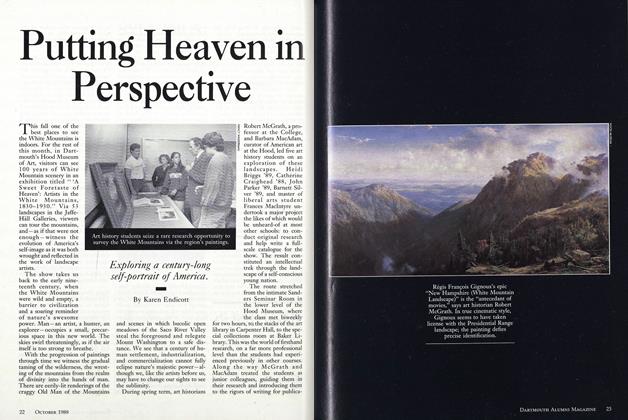

Cover StoryPutting Heaven in Perspective

October 1988 By Karen Endicott -

Feature

FeatureThe Zen of Football

October 1988 By Nick Lowery '78 -

Feature

FeatureScions Of The Times

October 1988 By Fritz Hier '44 -

Feature

FeatureChecking into the Inn and Out of an Era

October 1988 By John Townsley -

Feature

FeatureIs the Indian Symbol a Right or an Opportunity?

October 1988 By George B. Harris III '50 -

Article

ArticleFunded Research Rises

October 1988

Karen Endicott

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryThen lings get ugly

NOVEMBER 1992 By Karen Endicott -

Article

ArticleGaudeamus Igitur!

September 1993 By karen Endicott -

CLASSROOM

CLASSROOMWhy the Play’s Still the Thing

May/June 2001 By Karen Endicott -

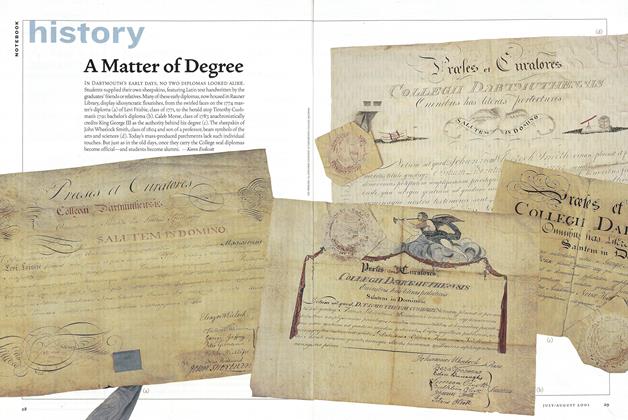

HISTORY

HISTORYA Matter of Degree

July/August 2001 By Karen Endicott -

Article

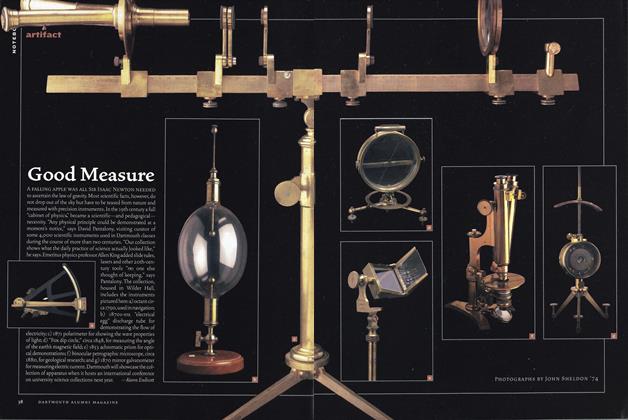

ArticleGood Measure

Sept/Oct 2003 By Karen Endicott -

Article

ArticleWHAT HAPPENED TO THE DEMOCRATS?

APRIL 1989 By Robert Arseneau, Karen Endicott

Article

-

Article

ArticleFRESHMAN CROSS-COUNTRY

November, 1909 -

Article

ArticleCHANGES IN COLLEGE CALENDAR AND COURSES

December 1918 -

Article

ArticleSouth Africa

MAY 1978 -

Article

ArticleTough Competition

April 2000 -

Article

ArticleA Man of "Leisure"

MAY 1964 By G. O'C. -

Article

ArticleSlow Tomatoes, Cajun Cooking, ana Crime

APRIL 1997 By Professor George Demko