Read a poem aloud, and

Teaching poetry at Dartmouth is like teaching poetry anywhere else: I have to overcome the strongrooted prejudice that poetry is esoteric, removed, and so difficult as to make it not worth the time it takes to decipher it. Mention poetry to anyone on the street and he will usually make a joke of the common "roses are red" variety or sheepishly apologize for his ignorance. As a poet I have come to love the experience of breaking down the stereotype. For example, in the freshman literature course I teach, the initial wariness and disbelief of students who sometimes have no interest in literature, let alone contemporary poetry, occasionally transform into an enthusiasm that leads them to major in our creative writing program.

Poetry is compelling not primarily because of its often intricate forms and meter or its important role in the literary tradition. Poems are potent because they take in conditions and events around us, and in a highly evocative, imaginative, condensed language give our life experiences back to us with a new relevance. Poems have the power to affect us in the most profound ways, even to change us. My goal in the classroom is to bring to my students poems that illustrate this truth. If the students are lucky, we are able during their time here to bring to campus one or two of the poets they study. When students are able to see and hear the work through the poet him or herself, as well as discuss the labor of writing, the concerns of the poet can seem remarkably like their own. The art that seemed so inaccessible, the artist whose most common image is that of a neurasthenic, mostly neurotic, reclusive or destructive alcoholic, comes home to their own sometimes quite ordinary lives.

"It's nothing more than a way of seeing," one of my freshmen said of poetry, and limited as that sounds, I have to agree. A memorable way of seeing, one that can grab for the jugular or one whose music stops your heart. But there are a lot of poems; and you have to read through a lot, sometimes even the entire work of a poet, to find the ones that speak to you. I tell my students to read a book of poems straight through, first page to last, and unless a poem creates a spark, not to read it again. Go on to the next page. But by all means, don't skip around: the poems were arranged in their order for a reason. A good book creates a kind of narrative, argument, or discussion as it progresses. A sense of the whole should emerge. If three or four poems in a book affect you, the book is successful. Read them aloud, slowly, and they will become yours. I tell my students not only to read a poem aloud but to write it out in longhand. (For those trying to write their own poems, this is also an invaluable learning experience.) The nature of good poetry, unlike fiction, is that by virtue of its form and relative brevity it offers itself to you. The poem, like a song, changes to suit the voice of its speaker, its content evolves to join the experience of the reader.

We need more poets at Dartmouth. We need them in our classes, not only in our textbooks. The art is thriving; the number of good poets who have been publishing in the second half of this century is impressive. As poetry has become more personal and self-revelatory—more transparent, it would seem it has also created a complex of new ways to look at the human condition. We have poets who have returned to the formal tradition of metrical verse and poets experimenting with a free verse line so long that it runs off the page. Allusion, myth, autobiography and the family, sex, ethnic and racial background, the subconscious, politics, the nuclear age, the environment, and the nature of language itself have all been explored and transformed by these writers. Never has poetry contained so much variety and spoken so clearly, direcdy, and honesdy. I offer you an example, a short poem by Pulitzer Prizewinner Mary Oliver, one of the many poets I hope will be brought to Dartmouth someday.

The Swimming Lesson by Mary Oliver

Feeling the icy kick, the endless waves Reaching around my life, I moved my arms And coughed, and in the end saw land.

Somebody, I suppose Remembering the medieval maxim, Had tossed me in, Had wanted me to learn to swim,

Not knowing that none of us, who ever came back From that long lonely fall and frenzied rising,

Ever learned anything at all About swimming, but only How to put off, one by one, Dreams and pity, love and grace How to survive in any place.

As a child, Cleopatra Mathis didn't like poetry. Even in high school, she says, she found the classic poetry her class studied to be "removed from the here and now." It wasn't until she student-taught a high school literature course that she found her way to poetry. "I was 19, almost the same age as the students I was teaching," she recalls. "I was bored with the usual groups of poets taught in high school courses, so I looked for the most recent poems from Modern British andAmerican Poets, the classic anthology of the time. As I tried to interest the students in poetry, linterested myself." After teaching high school for ten years, she pursued a Master of Fine Arts degree at Columbia, became a published poet, and in 1982 joined Dartmouth's English department.

Working from the students' interests is still Mathis's approach in the classroom as she tries to convey her conviction that literature provides a map for negotiating life. "College is a time when students are learning to make decisions for themselves," Mathis explains. "They need to be reminded that they have to walk through this experience with their eyes open. They are the ones who are going to change the world. Literature shows the path everyone has already taken before." Thus the professor starts her classes with readable contemporary essays by the likes of Joan Didion, Annie Dillard, and E.B. White about issues students confront every day. Then her students write about these things. Moving on to literature, they make what Mathis calls the "leap to the moral self" via Joseph Conrad's Heart of Darkness and works of William Faulkner. "Finally," she says, "students see that there's no difference between the characters they study and themselves: we're all dealing with the same issues."

Mathis says that she had wanted to be a fiction writer but found her wilting getting shorter and shorter, "hi fiction you have to read a lot of pages to find something that hits a chord, to find die magic where it all comes together. A good poem has that readily available," she says. Her own volumes of poems Aerial View of Louisiana, The Bottom Land, and The Center for Cold Weather, all published by the Sheep Meadow Press have earned her grants and awards, including the Academy of American Poets' Peter Lavan Award for Younger Poets. But perhaps most importandy, through her poetry Mathis enacts her view of life: "Make it matter."

"A good poem can provide strength forlife," says poet Cleopatra Mathis.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

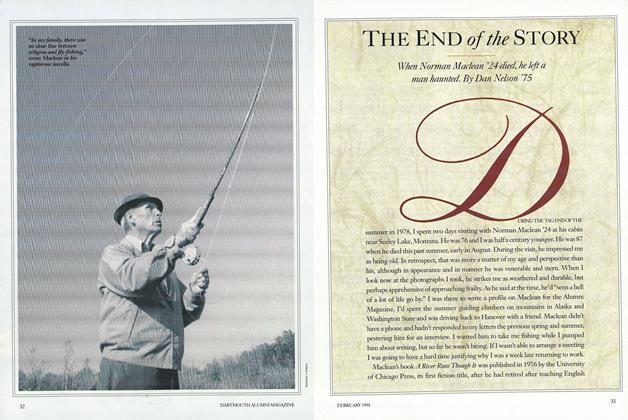

FeatureThe End of The Story

February 1991 By Dan Nelson '75 -

Feature

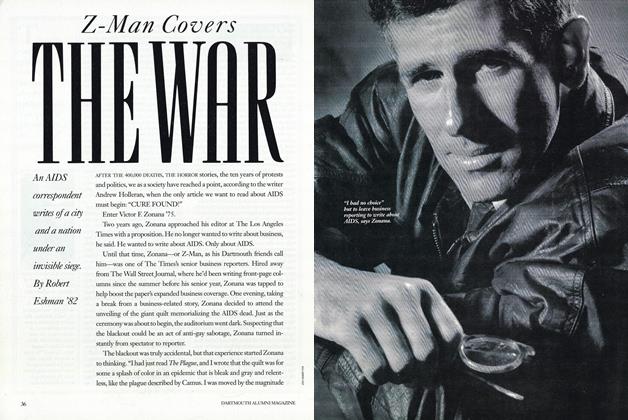

FeatureZ-Man Covers The War

February 1991 By Robert Eshman '82 -

Feature

FeatureOUR PASSIONATE PREFERENCE

February 1991 By Joseph D. Mathewson '55 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryNow For The Hard Part

February 1991 By Jay Heinrichs -

Feature

FeatureWHO OWNS DARTMOUTH?

February 1991 By Joe Boldt '32 -

Feature

FeatureIs Harvard Becoming More Like Dartmouth?

February 1991

Karen Endicott

-

Article

ArticleThe Corset Controversy.

October 1993 By Karen Endicott -

Article

ArticleCuring Fake Patients

OCTOBER 1994 By Karen Endicott -

Article

ArticleDid Science Kill Mother Nature?

November 1994 By Karen Endicott -

Article

ArticleControlling Self-Control

December 1995 By Karen Endicott -

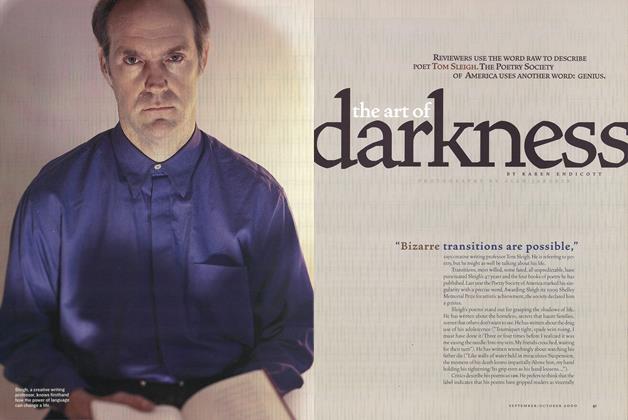

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe Art of Darkness

Sept/Oct 2000 By KAREN ENDICOTT -

Article

ArticleThinking About 9/11

Jan/Feb 2002 By Karen Endicott