MARK: "Don't tell me you're going to write about Dartmouth slang." Anne: "Why not?"

Mark: "That's the weakest topic for a column I've ever heard of."

Anne: "Why?"

Mark: "Well, for one thing, it's been done to death. Every year the 'D' runs a list of Dartmouth vernacular in the Freshman Issue, in the Winter Carnival Issue, in the Green Key Issue —"

Anne: "We never put out a Green Key issue."

Mark: "Don't quibble. You know what I mean. Nobody wants to read the same old list of expressions like 'Brew with the bro at the hou on the row.' And, frankly, nobody outside of Hanover really cares what 'brew' and 'the bro' and the rest of those mean."

Anne: "Fine, I agree. And that's why I want to do a column on Dartmouth slang that has a different tack."

Mark: "For instance?"

Anne: "Did you ever think that Dartmouth may be unique in having not just particularly popular slang words but perhaps the basics of a language all its own?"

Mark: "That's pretty dubious."

Anne: "And that's a perfect example of what I mean. Where outside of Flanover do you hear the word 'dubious' used so frequently? And not just 'dubious,' but 'marginal' and 'amazing' and 'incredible' and - once upon a time - 'awesome'?"

Mark: "Well, so what?"

Anne: "It shows that we, as a relatively homogeneous group of people living in a relatively isolated area, tend to adopt relatively obscure words and make them staples of our vocabulary."

Mark: "Huh?"

Anne: "Ask any anthropologist. Isolated tribes of a certain kingdom, though they may speak the same language as their fellow tribes, are often totally incomprehensible because of the preference they have for certain words and the change in meaning they impart to those words. The way we use 'marginal' and 'dubious' and the rest."

Mark: "I can see that, but that hardly means that we speak a different brand of English than they speak in Michigan or Wisconsin, or even in Cambridge."

Anne: "True, but think about it. If somebody really gets going at speaking Dartmouth slang, it's very hard to understand him unless you know some of the rules by which the words are formed."

Mark: "Rules? What rules?"

Anne: "Take an example. How often in the last four years have you said the word 'cocktails'?"

Mark: "I never say 'cocktails.' Nobody says 'cocktails.' We always say 'tails.' "

Anne: "Right. And that's one of the key rules: Chop the beginning or the end off a word, and you've got its Dartmouth equivalent."

Mark: "But where else would you do something like that?"

Anne: "I can think of a half-dozen examples offhand: 'za' for 'pizza,' 'nuts' for 'doughnuts,' 'shmen' for 'freshmen,' 'shrooms' for 'mushrooms' - I've even heard 'ner' for 'dinner.' "

Mark: "And 'pong' for 'beerpong.' "

Anne: "Right. And how many times in the last four years have you referred to the Economics Department as 'the Economics Department'?"

Mark: "Now, I've got you there. I can think of many terms I've applied to the Economics Department, but they're all pretty universal."

Anne: "No, no, no. I'm talking about, like, in a course title. Have you ever taken any courses in the department?"

Mark: "Sure: Eccy 1, Eccy 15 ... oh, I see."

Anne: "There. At most colleges they abbreviate 'Economics' as 'Econ,' but here it's 'Eccy.' "

Mark: "And 'Govy' for 'Government,' 'Socy' for 'Sociology,' I see what you're getting at."

Anne: "Cutting the end off a word doesn't just work for courses. Think how many times you use the word 'uni.' "

Mark: "But that doesn't strictly apply. 'Uni' doesn't really mean 'uniform.' You can talk about a 'smooth uni,' a nicelooking outfit; a 'uni party,' where people have to wear outrageous things; you can even talk about people 'uni-ing up.' "

Anne: "But even that sort of usage - giving a root word several forms and meanings - is typical of Dartmouth slang. 'Uni' is just one example."

Mark: "Name some others."

Anne: "How about 'ding'? We use it as a noun, a verb, an adjective - whenever we want to reject or negate something. You can receive a 'ding letter' from a Carnival date, or a med school, or a corporation with which you've interviewed. When you receive such a letter, you've been 'dinged' by the sender. If someone is so repulsive that you dislike him on sight, you give him, in your mind, a 'face ding.' And so on."

Mark: "You're right. 'Tool' is another. Someone is called a 'tool' if he studies a lot, or acts like he does. If he's studying, he's 'tooling,' and his behavior can be described as 'toolish.' "

Anne: "Right. 'Tool' and 'ding' are probably the most commonly used words of Dartmouth slang, and the most unique to Dartmouth. I've seldom heard them used outside Hanover."

Mark: "Fine, but we're back where we started. Every college has its euphemisms for someone who studies all the time, or for getting drunk, or for having sex."

Anne: "But Dartmouth slang goes beyond euphemisms themselves. As I said, it encompasses a set of rules by which they're formed."

Mark: "I'm still not convinced."

Anne: "Okay. If you knock over your beer, what's on the floor?"

Mark: "Okay. Spillage."

Anne: "And if your girlfriend sits on your lap throughout an entire fraternity party, what do your brothers give you grief for?"

Mark: "Excessive lappage."

Anne: "See? You've taken perfectly normal words and made them part of the Dartmouth vernacular by adding '-age.' You can do it for any noun: 'drinkage,' 'toolage,' 'bookage,' whatever."

Mark: "So adding suffixes like '-age' is one of the rules?"

Anne: "Yes. And adding prefixes is another. Like 'mega-.' If someone's making a lot of money, he's making —"

Mark: "Megabucks. I get you. And if someone's got a lot of studying to do, he has to —"

Anne: "Megabook. Right. You can even add suffixes and prefixes to the same words: 'megabookage,' 'megatoolage,' you know."

Mark: "'Megatoolage'?"

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureCould it be that the political animals are hibernating?

May 1978 By Anne Bagamery -

Feature

FeatureRev. Frisbie's Wonderful Discovery

May 1978 By James L. Farley -

Feature

FeatureCastles in the Clouds

May 1978 By George Hathorn -

Feature

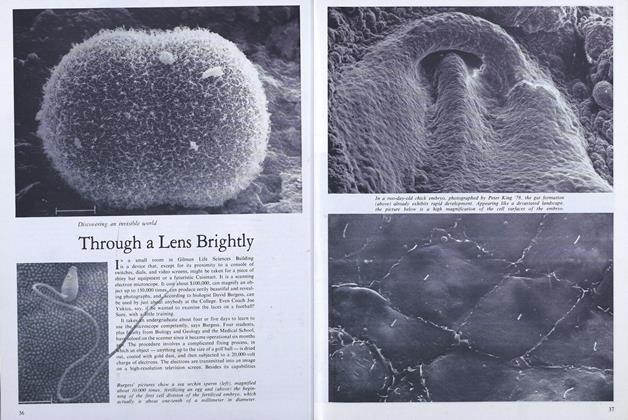

FeatureThrough a Lens Brightly

May 1978 -

Article

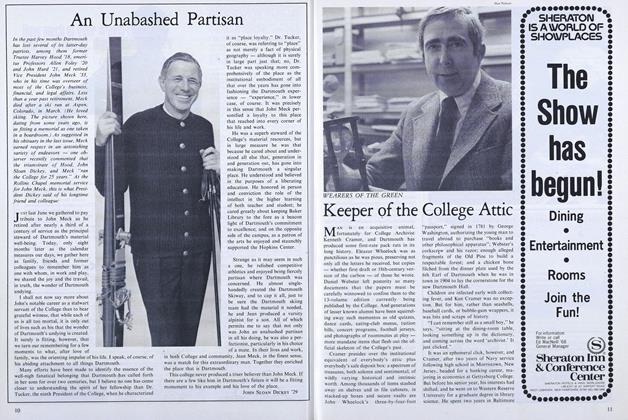

ArticleKeeper of the College Attic

May 1978 By M.B.R. -

Article

ArticleMy Dog Likes It Here

May 1978 By COREY FORD