I am convinced that the dilettante's liberal arts experience will turn out to be more practical than the eminently more marketable major in economics-modified-with - computer - programming - and - chemical-engineering. The reason? Within the framework of a truly liberal liberal arts program lies a whole realm of courses that teach the student nothing but facts he can really use. Every college and university has its name for these courses, and at Dartmouth they're called "distribs" — courses designed for use by non-majors to serve in fulfillment of the College's distributive requirement.

While a lot of good-natured grumbling goes on about being required to cram into one's program of study four seemingly useless courses from each division (Humanities, Social Sciences, and Sciences), distribs, if well-chosen and well-structured, can be the most informative and purely fun academic offerings at the College. For one thing, nobody really takes distribs that seriously, least of all some of the professors who teach them. This is not to degrade the commitment of said professors to said courses; it's just that nobody's kidding anybody else about why the course, and they, are there. One English professor notes that he could tell when his course became an accepted "easy Humanities distrib" when three-quarters of the students came to class with plastic lab goggles around their necks. And the professor of the now-defunct Biology 11 (Plants and Human Affairs) remarked to his 150-odd students on the first day of class, "You represent all classes, all majors, and all backgrounds, yet you have one thing in common: You have absolutely no use for this course."

The goal of the distrib therefore becomes giving the skeptical non-major his money's worth without destroying any of the light-heartedness both professor and student bring to the course.

There are a number of ways to spot a distrib, even without walking into the classroom. First, does the course have a cute nickname? Science distribs have the most recognizable ones: "Rocks for Jocks" (Earth Sciences 1 or 2), "Stars" (Astronomy 1 or 2), "Oceans" (Earth Sciences 3 — Oceanography), "Clouds" (Earth Sciences 4 — Meteorology), "Colors" (Science 10 — Light, Color and Vision), or — my personal favorite — "Earth, Wind and Fire" (College Course 3 — Earth, Moon and Planets). Not to neglect, however, the Humanities and Social Sciences distribs with intriguing titles: "Porno" (French 63 — Novel and Conte of the Eighteenth Century), "Nuts and Sluts" (Psychology 24 — Personality and Abnormal Psychology), and — so help me — "Gods" (Religion 1). One should be wary, however, of identifying a course as a distrib on the basis of the nickname: "Orgo" is kind of cute, too, but if the number (Chemistry 51-52) isn't enough to tip you off, the title (Fundamentals of Organic Chemistry) should.

Next, you should be able to isolate those students who have taken, or are presently enrolled in, a distrib. Listen carefully to their dinner-table conversation. Is it peppered with such tasty tidbits of information as, "Drink hot chocolate to stay awake — it has twice as much caffeine as tea" (Biology 11); "Getting out of bed has the same effect on your heart as the first stages of a heart attack" (Biology 1); or, "Did you know there's this ram in South America that can..." (Biology 2 — Human Reproduction)? If so, you can comfortably rest your case.

In the classroom, though, the "distrib" nature of the course can hardly be missed. Physics Professor John Kidder's Science 10 lectures, for example, are full of references to items "that should be useful to you art majors"; retired Biology Professor Roy Forster once told his Biology 1 class that students would study a certain concept in greater depth "if you continue in biology — which is unlikely"; and an English professor teaching Science Fiction (English 29) one term began a textual analysis of one of the readings by saying, "Now, for those of you who have never read a novel in a course here...."

That's what's so refreshing about distribs. Since they don't carry the expectation of high-intensity academic performance that upper-level major offerings do, distribs can be beautifully unassuming. Nobody who signs up for Plants and Human Affairs as part of his science requirement is seriously entertaining thoughts of being the next Euell Gibbons, and certainly nobody expects him to. He will, however, be able to tell the age of a twig by looking at its wrinkles and will know how much curare it takes to kill a buffalo. Distribs set their goals at providing some practical knowledge and an introduction to thinking in a certain way, and let it go at that.

The low-key approach to any subject matter can be wonderfully sanity-saving, too. Picture the poor sophomore biochemistry major who is socked into Organic Chemistry and Cell Biology and wants some time to eat, sleep, and breathe during his term. Aha — SciFi as a third course! A distrib to the rescue. Or, picture a last-term senior finishing up her thesis (see "The Undergraduate Chair" for January/February) and taking one other course in her major besides. Would you begrudge her the relief of Kidder's "Colors" as a third? I thought not.

Lest the impression be given that students take lightly the gung-ho efforts of professors teaching distribs, let me point out that many faculty look to distribs as a sort of relief as well. Forster said he liked Biology 1 because "I could throw my weight around, because I knew what I was talking about so well." And Science 10 gives Kidder an annual break from his specialty (low-temperature physics and cryogenics) to indulge a personal curiosity about the properties of color vision. Besides, he says teaching science to nonscience majors "keeps me from taking myself too seriously."

As I said before, I believe in the value of the liberal arts education — the philosophy of which makes distrib courses an integral part of the curriculum. But, as should be obvious by now,' the real reason for teaching distribs — or for even harboring such an animal as liberal arts — has nothing to do with broadened horizons or expanded intellectual capacity. Frankly, the reason we liberal arts types did not opt for chemical engineering at Cal Tech even though such a choice would land us a job next year faster than a degree in Romance Languages will - is that, in the cocktail parties of this world, chemical engineering just does not cut the conversational mustard. Now, on the other hand, if you want to know more about that South American ram....

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureStalking the Student Athlete

March 1978 By Dan Nelson -

Feature

FeatureThe New Classics

March 1978 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

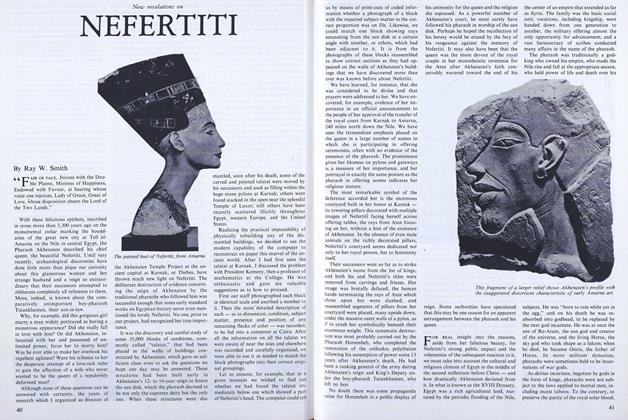

FeatureNEFERTITI

March 1978 By Ray W. Smith -

Feature

FeatureFaces in the Gallery

March 1978 -

Article

ArticleAn Untraditional Path

March 1978 By A.E.B. -

Books

BooksNotes on a Yale man's journal and the 'elbowing self-conceit of youth.'

March 1978 By R.H.R.

ANNE BAGAMERY '78

Article

-

Article

ArticleThe degree of rapidity with which reports

December, 1910 -

Article

ArticleThings Won't Run as Well Now That He Has Retired

November 1955 -

Article

ArticleFall Reunions

SEPTEMBER 1981 -

Article

ArticleMatthew Marshall: Keeper of the Inn

MARCH • 1986 By Georgia Croft -

Article

ArticleViet Nam: The Greater Tyranny

OCTOBER 1965 By JOHN LAMPERTI -

Article

ArticleNotebook

Jan/Feb 2009 By JOHN SHERMAN