Amid Dartmouth's small cathedrals of books, a writerescapes from "secular reality? By Alan Lelchuk

The experience repeated itself, with certain changes, a half dozen years later, when I spent a graduate year studying in London, and reading in the Reading Room of the British Museum. Allowed entrance (only) with a scholarly ticket, I stepped inside that grand circular room capped by a high golden dome, and once again felt myself in a world apart, a place elsewhere, where reading was the name of the religion. After checking the huge, battered catalogs where book information slips were pasted on the thick pages like a child's ancient game, I ordered my books from the center cage, and then found my seat in one of the serpentine curved rows, to wait. I had five or ten minutes to get ready, light switched on, notebooks, pen, and pencils out, my neighbor frilly adjusted, before my books arrived via wheeled cart and stack-messenger. Gradually then, the dominion of books spread itself, and ordinary reality, secular reality you might say, receded. Readingwith its precise rules of behavior and implicit beliefs—ruled.

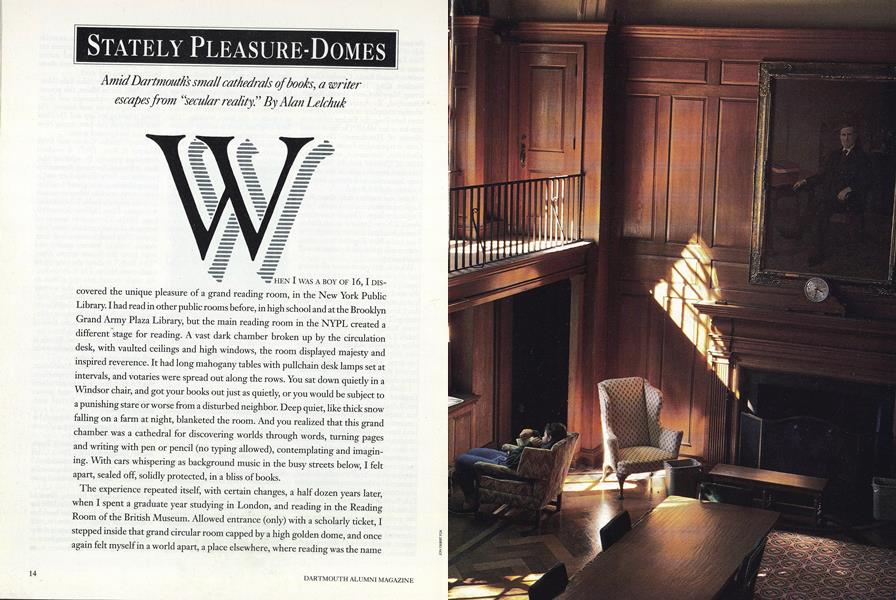

In similar ways, I am enchanted by the rooms I read in at the College. In the Tower Room late at night, surrounded by dark walnut and oak woods, I find a place either at one of the long tables by a green desk lamp, or slip into a tattered wing chair in a separate area between bookshelves, and there, beneath an old-fashioned standup lamp, I read. While the rooms are neither as grand nor as solemnly quiet as the BM or NYPL reading rooms, and the rules do not really permit you the proprietary pleasure of staring down or silencing a noisy patron, still, they qualify as authentic. The undergraduates here are relatively quiet, if not quite fully converts yet. Besides my appointed reading, I am also tempted in Tower to browse, an art in itself for the addicted reader. Novels and literary biographies catch my attention, and for 15 or 20 minutes I forsake my own reading to stray errantly, and catch up on a never-read Mary McCarthy, say.

The cozy lengthiness of the rooms also spurs me to stroll, and I find myself meandering periodically, stopping by the solitary wooden desk and leather-covered round table in the center, upon which sits the sculpture of a Native American sitting regally atop a horse. My mind is still humming with the pages I have just read, since browsing and idle ambling are very much within the boundaries of behavior, within the realm of reverie, for the serious reader.

Interestingly enough, my reading habits change when I read, for example, in the basement of Baker. Beneath the aggressive figures of the Orozco frescoes, I find myself focusing on long narratives, texts like Stegner's Beyond the Hundredth Meridian or Tuchman's Stilwell and the American Experience in China, as though I need there a continuous narrative force to counter the stark visual force. And it works too. I mean, reading takes hold despite the powerful images looming above, despite the whispering busyness of the Reserve area. I read in the basement by day only, however, finding that reading there at night is overwhelmed by opu-lent lent Orozco; his stylized nudes and Antichrists intensify in the evening. Besides, night reading needs lamps, upholstered chairs, out-of-the-way niches. Every reader, especially of middle age, knows that.

In Sanborn, I sit upstairs on the balcony level, tucked away in an alcove, peering out at the sweep of green and imagining distant places or nearby characters, in reality or fiction. Collections of literary essays, by such as Rahv or Jarrell; familiar poetry, by Donne, Stevens, or Bishop; recent Atlantic or Sewanee Review pieces that I've been carrying around with me; that's the stuff of my reading there. A room for belles lettres, an alcove for contemplating, amidst stacks and stacks of books.

I try to read at Sanborn during and around the dinner hours, when the small library's old-world elegance is in full force, featuring dark woods, curving staircases, tiers of old books. The occasional student studying then seems to fit in well with the aura of library—not a mere student, I hope, but a budding reader.

"Stately pleasure-domes" these reading rooms, to rephrase Coleridge, at least for me. The Tower Room, Baker basement, Sanborn, these are rooms free of Apples, discs, Word 4.0 wisdom, and filled instead with long tables and high windows and the aroma of books. That is to say, they are filled with the requisite magic of yesteryear, when space, quiet, books, were all that were necessary for the imagination to roam, the mind to think clearly. For what is reading but interior freedom and discovery, a spiritual journey down through the winding centuries of the human imagination?

And perhaps especially in these Macintosh-McLuhanesque days, it might be said that reading is a cunning pleasure, stolen on the sly from modern technological life. For to make reading a regular pursuit, to pursue it as a daily devotion in adult life these days, one has to stay shrewd, stay resistant, play the fugitive. You know, fight off the delights of movies, records, friends, trips, conferences, dinner parties, and hide out, with a book. In any case, these Dartmouth mini-domes of pleasure remind me of my old grand reading palaces, and I return to them regularly with old ardor and cherished routine.

"To makereading aregularpursuit, topursue it as adaily devotionin adult lifethese days, onehas to stayshrewd, stayresistant, playthe fugitive"

Alan Lelchuk teaches in Dartmouth's Masterof Arts in Liberal Studies program. His fifthnovel, Brooklyn Boy, was published earlythis year.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

Features

-

Feature

FeatureAvalanche Authority

JUNE 1973 -

Feature

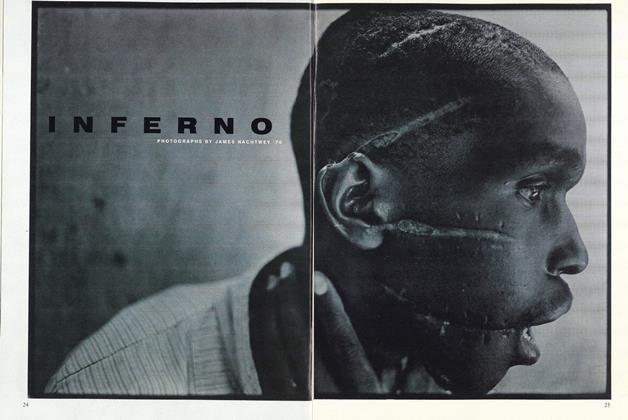

FeatureInferno

JUNE 2000 -

Feature

Feature"The Record of Their Fame"

December 1954 By FORD H. WHELDEN '25 -

Feature

FeatureHow I Invented Dog Running

June 1989 By John F. Anderson '34 -

Feature

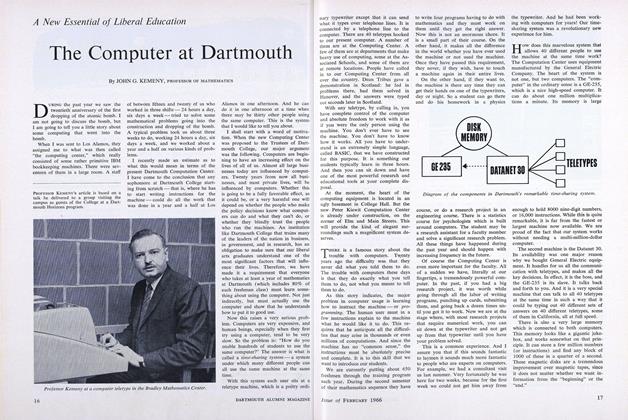

FeatureThe Computer at Dartmouth

FEBRUARY 1966 By John G. Kemeny -

Feature

FeatureNotebook

Mar/Apr 2012 By JOSEPH MEHLING '69