/n 1968 the Board of Trustees voted a major new program to provide equal opportunity for minority students at Dartmouth. To make more detailed recommendations on the new program and to monitor its progress, a committee on equal opportunity was established, consisting of faculty, administrative officers, and students. It so happened that I was the faculty member chosen as its first chairman, and this would lead to one of the strangest experiences in the history of the College.

One of our tasks was to spell out in detail just how the equal opportunity program should be structured. We were beginning to realize that it was not enough to admit a significant number of minority students because quite substantial financial support and faculty and administrative help was essential for the success of the program. The equal opportunity committee recommended that the College concentrate its efforts in three major areas. Because of the enormous national problem facing black Americans, we recommended that highest priority should be given to the admission and support of black students. Secondly, because of the unique history of the College, we recommended a special program for American Indians. Thirdly, because of the traditional role Dartmouth has played in its own region, we recommended special consideration for students from poor families in the three northern New England states.

This set of recommendations reached the 12th President of the College at a time when he knew that his successor would shortly be picked, and he decided that the decision should be made by the 13th President. It was thus that on my first day in office I found on my desk recommendations from me as chairman of the equal opportunity committee to myself as President of the College. I am happy to report that I approved the recommendations. Had I turned them down, we would have had a plot for a Gilbert and Sullivan operetta!

The College still needed to learn an important lesson: it is much easier to give enthusiastic approval to a program of equal opportunity than to make it totally successful. It is hard to bring large numbers of black and Native American students to one of the most predominantly white regions in the United States. While black students, many from urban areas, often find Hanover bewildering, Native American students, particularly those coming from reservations, have an even more difficult task of adjustment. It was essential to attract to the College, both in the ranks of the faculty and the administration, individuals who would serve as "role models" and who would have first-hand experience with the problems and frustrations confronting minorities. Their caliber has been high, but we have found that the demand throughout the country far exceeds the current supply and we have lost a number of key individuals to betterpaying positions at other institutions.

Today, roughly ten per cent of the freshman class consists of blacks and Native Americans. We have had a number of spectacular successes, including black Rhodes Scholars and a Native American student who currently serves in the New Hampshire legislature. We have also had a number of failures.

The failure rate has been particularly high among Native American students, and I am now convinced that we made serious mistakes in the way we tried to attract these students. This year Eddie Chamberlain has instituted a "talent search" through the facilities of the College Entrance Examination Board, which should give us a much better reading of where talented Native American students are receiving an education that can prepare them for Dartmouth. We will bring promising candidates to campus so they can talk to students and faculty members and form a judgment as to whether Dartmouth is the right school for them. This process should go a long way toward broadening the base from which we recruit Native American students and should make sure that they arrive on campus with an understanding of what the College expects of them.

There is considerable misunderstanding of the nature of the commitment made to the equal opportunity program. The College has made a commitment to admit minority students whose credentials on entrance would not have qualified them under traditional criteria, but the College has not changed the graduation requirements or the academic standards for graduation for any of its students.

To understand the nature of the changes in admissions criteria one must ask whether such traditional measurements as College Board scores are fair to students coming from an inner-city ghetto or from a reservation. Tests that are supposed to be pure tests of aptitudes have strong social conditioning. This is perhaps clearest in the case of the so-called verbal aptitude test, which is now under intensive review by CEEB. While it was designed to measure a candidate's ability to absorb verbal information, to use verbal arguments, and generally to command the English language, the test in fact assumes an upper-middle-class background. Some very bright students, who would make outstanding college material, are severely handicapped in these tests by being brought up in families where they hear an extremely limited vocabulary. Indeed, some of the vocabulary in former SAT tests was so esoteric that many students would find the words irrelevant to their college work. Our admissions office is faced with the major challenge of identifying true talent even if it cannot prove itself on traditional tests. This makes our judgments much less certain, and hence the phrase "high-risk students." Because of this uncertainty the failure rate among minorities has been somewhat higher than traditional at Dartmouth, but the vast majority of our black students have successfully graduated from the College in four years, and a number of high-risk admissions have turned out to be spectacularly good students at Dartmouth. I consider this degree of risk an excellent trade-off for having among the alumni of the College hundreds of students who would otherwise never have had an opportunity for a Dartmouth education.

The second major commitment made by the Trustees and the faculty was to give extra help to students who come from weak secondary schools. This help has taken a variety of forms. We have a summer "bridge program" for students with particularly weak backgrounds. The faculty has made itself available for outside-of-class help to students, and we have provided tutoring by other students. The demand for extra help existed before the launching of the equal opportunity program, and it is simply that the number of students who need such help during their freshman year has increased significantly. We have also found a need for much more personal counseling, particularly by members of the same minority group, to help students through the "culture shock" of living in what is to them at first a very strange environment. I believe that as the College gets better at providing this kind of help our rate of success will continue to improve.

I discussed the academic programs in black studies and Native American studies elsewhere in this report. Only indirectly related to the equal opportunity program, they provide evidence to our minority students that the institution cares about non-white subcultures in America. We have not provided any special majors for minority students since they wish to major and succeed in exactly those subjects and fields where Dartmouth students have traditionally tried to excel. Although they do enjoy the chance to examine black literature, for example, our black students have not come to Dartmouth to become experts in black studies. They want to become doctors and lawyers and businessmen and scientists. Nor have they asked for a lowering of academic standards. I have heard black students argue most vigorously that it would be a disaster if Dartmouth established a dual standard. Of what value would a Dartmouth diploma be if we allowed them to earn it without meeting the traditional high standards of the College?

The ultimate success of equal opportunity programs here and elsewhere will be to create a racially fair society which will no longer need equal opportunity programs.

Features

-

Feature

FeatureBOSTON'S 100th ANNIVERSARY DINNER

MARCH 1964 -

FEATURES

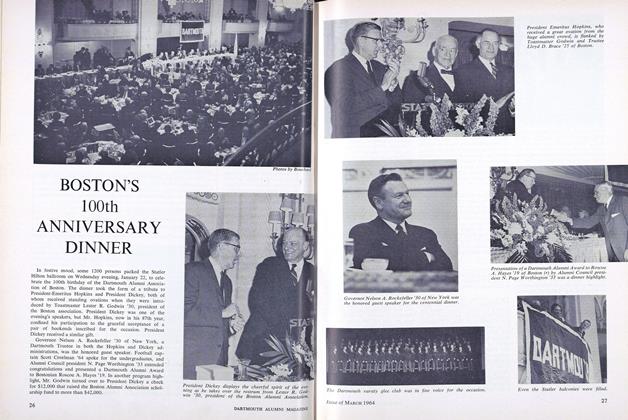

FEATURESMy Dog Likes It Here

MARCH/APRIL 2023 By COREY FORD -

Feature

FeatureConquest of the Antarctic

June 1957 By DAVID C. NUTT '41 -

Cover Story

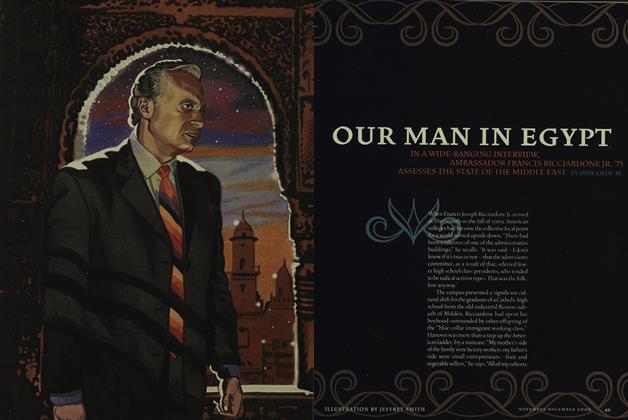

Cover StoryOur Man in Egypt

Nov/Dec 2006 By DIRK OLIN ’81 -

Feature

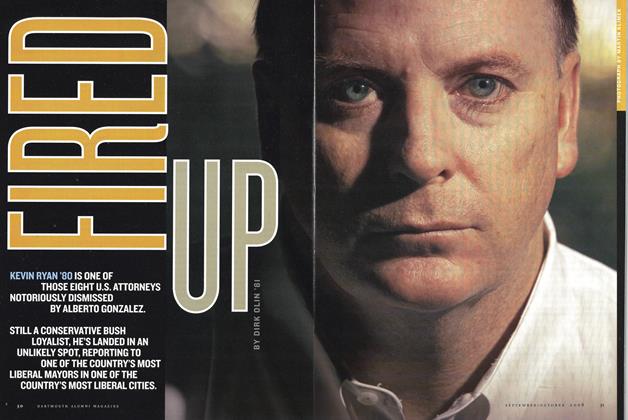

FeatureFired Up

Sept/Oct 2008 By DIRK OLIN ’81 -

Feature

FeatureWhy I Traded Basketball for Biology

MARCH 1989 By Liz Walter '89