"Am I alone," wrote Albert Archer '22, "in being discouraged by the obvious trend of the policies of the College, the undergraduates and faculty in Hanover?"

Of course, Archer was far from alone when he wrote that lament to the Alumni Magazine in 1954. Within years of the College's founding, its faithful have seen alarming changes. In the late eighteenth century, English donors cried betrayal when Eleazar Wheelock abandoned his Indian charity school in favor of an institution for budding missionaries. In 1893, when plumbing entered dormitories, alumni feared that students would turn soft and effeminate. And by 1913, Daniel Webster's "small college" had grown so large that the freshman beanie was introduced to distinguish the classes.

Ever since, those who love Dartmouth have wondered aloud whether the College has lost the essence that made it great in the past or achieved a new greatness at the cost of its soul. For two centuries people have asked, Is Dartmouth still Dartmouth?

The problem is, the true College' varies greatly in the eyes of beholders, especially those of different eras. If the school isn't what it used to be, when was Dartmouth Dartmouth? What was the real College of old? Was it Moor's Charity School? Was it the Dartmouth of the nineteenth century, a college still divided by a Supreme Court case which resulted in loyal Democrats' sending their sons to other schools?

Was it the Dartmouth of Nathan Lord, who broke up campus riots with his cane? Or of Ernest Martin Hopkins, who had the maddening habit of hiring rabble-rousing faculty after they had been drummed out of less tolerant institutions? Or of John Dickey, whose Great Issues course for seniors allowed them to gnaw on public bones of contention? Or of John Kemeny, who opened the College to women? Or of David McLaughlin, who oversaw the rise of the endowment and the decline of the fraternities? Clearly, whatever past era constitutes Dartmouth's epitome, the present version is different.

Today the College faces some of the most crucial choices in its history. How can it recruit the best faculty without the large resources of major universities? How can it attract more intellectually inclined undergraduates, and inspire the entire student body to study harder, without losing students' traditional commitment to public service, athletics, gregariousness, institutional loyalty and leadership? How can it continue to support an impressive diversity of programs for a small student body without putting tuition out of the reach of average citizens?

If the past 200 years are any indication, the answer will remain elusive. Clearly, Dartmouth is on the verge of a great period of change; but then, at its most vital, it always has been. From Eleazar Wheelock's innovative religious teaching to Professor Jon Appleton's experimentation with computerized music, Dartmouth has remained on the frontier. Thus even today's freshmen will likely find the campus shockingly changed when they return for their tenth reunion in 2002.

To help cushion the blow, and to allow alumni the chance to participate in and comment on change, the Alumni Magazine has made some alterations of its own. A redesign and some new departments will, we hope, reflect the College's renewed academic vigor while reminding readers of Hanover's continuing beauty.

In addition, an occasional series of major articles, written by alumni who rank among the nation's top journalists, will examine the College's basic underpinnings the faculty, campus architecture, the curriculum. Published under the logo, "Is Dartmouth Still Dartmouth?", the articles will attempt to measure the degree to which the campus resembles the College of old whatever that is and how much it is changing. The first in the series, on admissions, follows.

Alarming changeis one of theCollege's mostlasting traditions.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryWelcoming the Loner

September 1988 By Victor F. Zonana '75 -

Feature

FeatureFrom America's Lost Cohort, the Shards of Souls

September 1988 By David R. Boldt '63 -

Feature

FeatureIn the Galactic Search for Intelligence, We May Find Ourselves

September 1988 By Jack Baird -

Feature

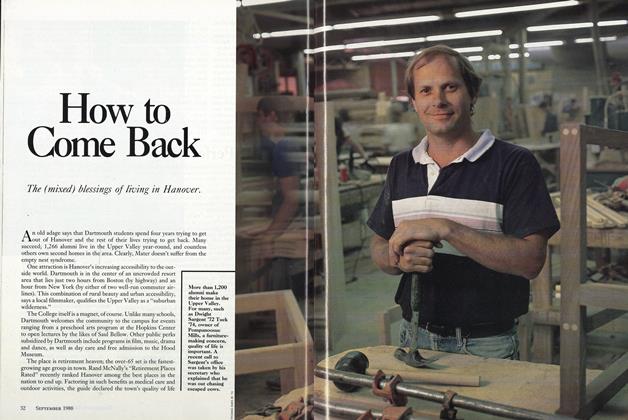

FeatureHow to Come Back

September 1988 -

Sports

SportsFall Sports Preview

September 1988 -

Article

ArticleRush Delayed

September 1988 By Jack Steinberg '88

Jay Heinrichs

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryShould The College Change Its Tune?

APRIL • 1987 By Jay Heinrichs -

Cover Story

Cover StoryNow For The Hard Part

FEBRUARY 1991 By Jay Heinrichs -

Feature

FeatureELECTRIC BODY LANGUAGE

SEPTEMBER 1991 By JAY HEINRICHS -

Cover Story

Cover StoryChoices

September 1992 By Jay Heinrichs -

Article

ArticleNels Comes Home

April 1995 By Jay Heinrichs -

Outside

OutsideRunning With Wild Abandon

July/Aug 2002 By Jay Heinrichs

Features

-

Feature

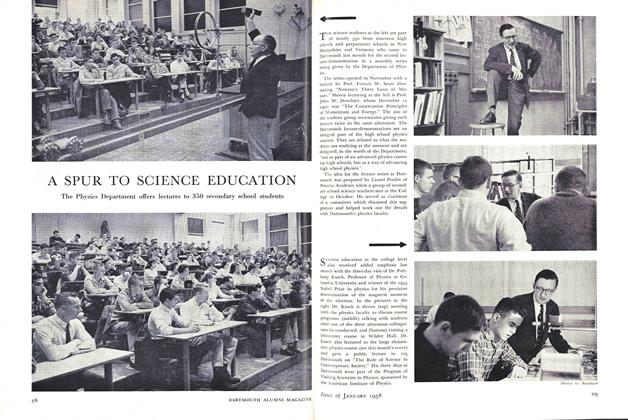

FeatureA SPUR TO SCIENCE EDUCATION

January 1958 -

Feature

FeatureDays of Controversy: 1816-1819

June 1962 -

Feature

FeatureImpacts simply positive

MAY 1982 -

Feature

FeatureLooking for Mister Right Stuff

Novembr 1995 By Jane Hodges '92 -

Feature

FeatureThe Meaning of Emeritus

July/August 2001 By Jay Parini -

Cover Story

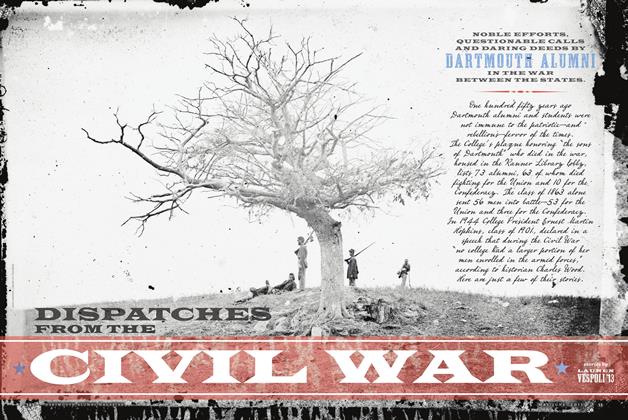

Cover StoryDispatches from the Civil War

May/June 2013 By LAUREN VESPOLI ’13