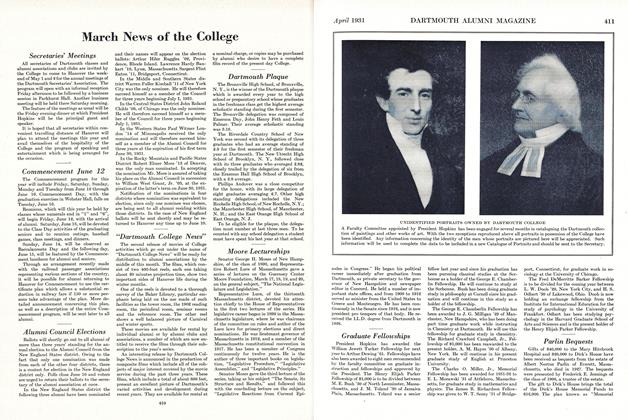

"Leaders with a command of language and thought have inspired their fellow citizens to hold fast to their moral bearings."

As the president of a college that emphasizes the education of undergraduates, I am often asked by people outside academia whether liberal education has any relevance to what is too often called the "real world." As an answer, I would like to borrow from the address I gave last June at Dartmouth's Commencement.

There is no better time to ask what the life of the mind has to do with the life of the world than now—a time when the peoples of Poland, Hungary, East Germany, Czechoslovakia, and Romania have wrought a renaissance of the ancient values of political democracy and individual liberty. During the bitter decades of the Cold War, the governments of Eastern Europe had enforced a tyranny of thought. Language descended into a vehicle, in the words of George Steiner, of "totalitarian lies and cultural decay," of "murderous falsehoods" and hollow vulgarities.

But in the end, as we have discovered anew, all of the attempts to suffocate language could not suppress the idea of freedom. To a degree unusual in the modern era, the democratic revolutions in Eastern Europe have vindicated the transforming power of language and established still again its historic connection to political freedom.

No one in recent times has demonstrated this more perfectly than Vaclav Havel. In a series of remarkable addresses delivered in the months since he became president of Czechoslovakia, Havel has employed language to vault over the mundanity of governmental hypocrisy and strive for the higher ground of conscience and idealism. "The salvation of this human world," he told the U.S. Congress last February, "lies nowhere else than in the human heart, in the human power to reflect, in human meekness, and in human responsibility." These words, spoken just four months after his release from prison and two months after his election as president, prove Shelley's assertion that "poets are the unacknowledged legislators of the world."

Havel's example—who would have believed that a modem nation would choose a playwright as its president? reminds us that intellectuals matter in the daily conduct of democratic affairs. They matter because they express ideas more clearly than the rest of us. They matter because they are able, by their command of language, to summon us to a higher vantage point of observation upon the moral horizon of our lives. From Boris Pasternak to Alexander Solzhenitsyn, from Thomas Mann to Gunter Grass, it has been intellectuals who have invoked most prominently the power of language to express the resolute truths of political destiny.

The phenomenon has not been confined, however, to the nations of continental Europe. Abraham Lincoln spoke in language of a Biblical simplicity when he formulated anew the meaning of democratic government and sought to heal the awful wounds of war. Winston Churchill relied upon the stirring power of Ciceronian rhetoric, during the pitiless bombing of London, to rally the indomitable spirit of the British people. Martin Luther King Jr. drew upon an ecclesiastical eloquence in stating the undeniable claim of equality upon realization of the American dream.

The renaissance of democratic values in Eastern Europe thus reflects a larger historical pattern a pattern that emphasizes the power of language and the role of intellectuals in inspiring their fellow citizens to hold fast to their moral bearings.

President Havel would doubtless acknowledge that the value of intellectuals can be overstated. But a country which, as Richard Hofstadter once commented, has made anti-intellectu-alism "a familiar part of our national vocabulary of self-recrimination and intramural abuse," hardly faces a clear or present danger of overvaluing the participation of intellectuals in public affairs. Our obligation still is to appreciate that when intellectuals join their capacities of language and thought to the pragmatic arts of statecraft, they can enrich the quality of public life. For the gift of teaching us, by their example, that liberal education seeks the preservation of humane values and the maintenance of individual responsibility for the common good, they deserve our deepest gratitude.

GEORGE CALEB BINGHAM; GOUPIL & COMPANIE, DETAIL FROM STUMP SPEAKING 1856. COURTESY HOOD MUSEUM. PURCHASED THROUGH THE JULIA L. WHITTIER FUND.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe Real Story Behind the Lower Forty Shooting, Angling and Inside Straight Club

September 1990 By Robert Sullivan '75 -

Feature

FeatureSeidman's Early Withdrawal

September 1990 By Susan Dentzer '77 -

Feature

FeaturePROBLEM SOLVER

September 1990 By John Aronsohn '90 -

Feature

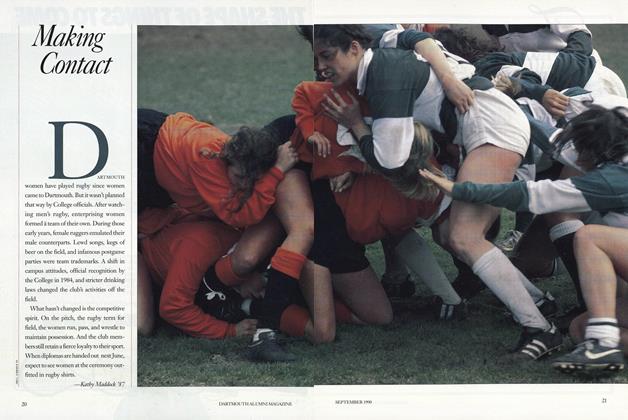

FeatureMaking Contact

September 1990 By Kathy Maddock '87 -

Article

ArticleMOTHERS AND DAUGHTERS

September 1990 By Professor Marianne Hirsch -

Article

ArticleDR. WHEELOCK'S JOURNAL

September 1990

James O. Freedman

-

Article

ArticleORIGINALS AND COPIES

JUNE 1991 By James O. Freedman -

Article

ArticleTHE SENSE OF PLACE

SEPTEMBER 1991 By James O. Freedman -

Article

ArticleTHE HEROIC OUTSIDER

December 1991 By James O. Freedman -

Article

ArticleA Postponed Power

May 1993 By James O. Freedman -

Article

ArticlePreparing for Contingencies

December 1995 By James O. Freedman -

Article

ArticleStaying Out of the Groove

SEPTEMBER 1997 By James O. Freedman