When Norman Maclean '24 died, he left a man haunted.

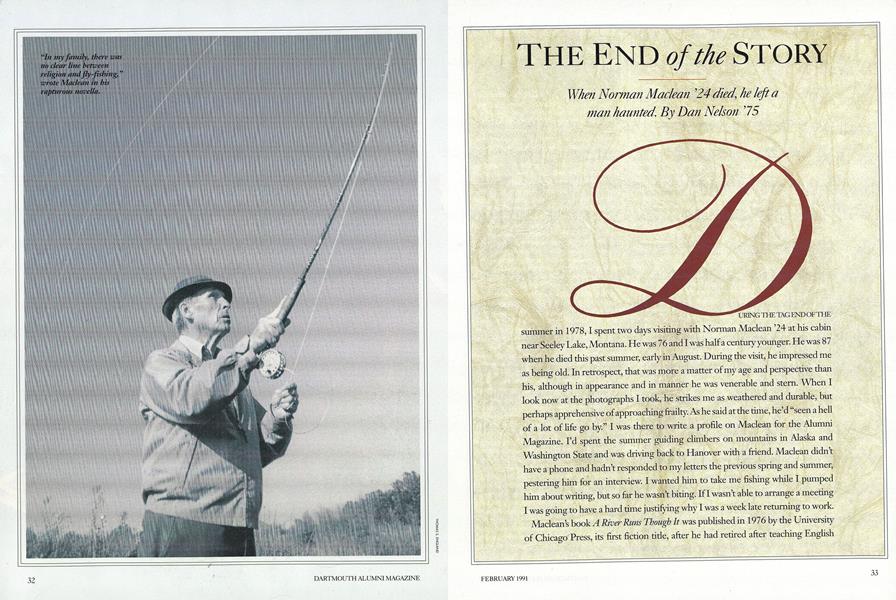

summer in 1978, I spent two days visiting with Norman Maclean '24 at his cabin near Seeley Lake, Montana. He was 76 and I was half a century younger. He was 87 when he died this past summer, early in August. During the visit, he impressed me as being old. In retrospect, that was more a matter of my age and perspective than his, although in appearance and in manner he was venerable and stern. When I look now at the photographs I took, he strikes me as weathered and durable, but perhaps apprehensive of approaching frailty As he said at the time, he d seen a hell of a lot of life go by." I was there to write a profile on Maclean for the Alumni Magazine. I'd spent the summer guiding climbers on mountains in Alaska and Washington State and was driving back to Hanover with a friend. Maclean didn't have a phone and hadn't responded to my letters the previous spring and summer, pestering him for an interview. I wanted him to take me fishing while I pumped him about writing, but so far he wasn't biting. If I wasn't table to arrange a meeting I was going to have a hard time justifying why I was a week late returning to work.

Maclean's book A River Runs Though It was published in 1976 by the University of Chicago Press, its first fiction title, after he had retired after teaching' English there for 45 years. Along the way, he had been named to the William Rainey Harper chair in the English Department and he had been a three-time recipient of the Quantrell prize for excellence in teaching undergraduates. No one else had won it more than once. The book comprises two novellas and a short story, and it is fiction in only the loosest sense. In its language, which is anything but loose, in its details, and in its vision, it is true all the way through. In a review published in 1989, Alfred Kazan described Maclean's expressions of "physical rapture in the presence of unsullied primitive America...as beautiful as anything in Thoreau or Emerson." Maclean, on the other hand, has referred to his book as "a collection of western stories with trees in them." He told me with evident satisfaction that no one had ever challenged the accuracy of anything in it presented as factual. Largely autobiographi- cal, the stories have to do with growing up in western Montana, hard work in the woods and mountains, the Forest Service, family, love, friendship, and loss. One of the characters is Maclean's brother Paul, "the best fly fisherman I ever saw," a hard-drinking, gambling, brawling newspaperman who graduated from Dartmouth in 1928 and was found murdered in a Chicago alley in 1938.

After I completed my senior year at Dartmouth and my undergraduate internship with the Alumni Magazine, and before I knew I would be returning the next fall as part of the staff, the editor, Dennis Dinan '61, gave me a copy of Maclean's book as a going-away present. It's a book I continue to give to friends who have a special love for outdoors for places that haven't yet been spoiled by people's enjoyment of them and for the friendships formed there or to friends with whom I'd like to share something that expresses part of how I'd like to define myself. It's a book I treasure because it is full of things I love and value. Sometimes the book has preceded and prompted a friendship: when I've heard others talk about how they have responded to it, they've ceased to be strangers. After I read it for the first time, I had the sense that its giver was welcoming me, a graduating senior with literary aspirations and outdoor enthusiasms, into a circle of friends who shared a sense of language, avocation, and vision. I also had the sense thabesides an invitation, I'd been given a challenge and a text to study, as though the giver had said, "If you want to write, particularly if you want to tell the truth, measure your efforts against this. If you are serious about friendship and fishing and the outdoors, about finding your way toward living with some kind of consistency and integrity, read this and see if you can come close."

So before I even met Maclean, he was a kind of literary and moral hero. A guru. From all initial appearances, he didn't have the slightest interest in meeting me. When I finally found him home for the summer at Seeley Lake (I drove to the nearest town and followed the postmaster's directions to the log cabin built in 1922 by Maclean and his father), he had a letter addressed to me on the mantle. Its content, he was quick to note, advised me not to bother with the visit. He was busy. He was tired of guests. He'd been interviewed before. He was fished out. But there we were, and fortunately for me, he pegged the friend I was traveling with as less of a nuisance than I was likely to be. Western hospitality prevailed. He invited Betsy and me to come inside. He was generous with his time and with his memories.

He grew up in Missoula, Montana, the son of a Presbyterian minister who saw the world in a way that prompted Maclean to begin his book by writing, "In my family, there was no clear line between religion and fly-fishing." He had summer jobs working for the Forest Service, and after he graduated from Dartmouth, where he had been editor of the Jack-O-Lantern, he accepted Professor David Lambuth's invitation to stay at the College to help him teach a course or two. Maclean said he accepted the invitation "because the class was full of some poker buddies of mine, and I figured it would be a good way to pay back some debts." He also said he hated teaching, at least at first, and after his father told him he seemed to be stagnating, he went back to the Forest Service. Two years later, after marrying Jessie Burns, a woman he met at a Christmas party on a sheep ranch, he began graduate school and started teaching at the University of Chicago, where he stayed until retirement in 1972, serving a stint early on as dean of students. Jessie Maclean died in 1968, and Maclean said that his decision as a man in his 7Os to write fiction was an attempt to rebuild his life. "She was dead, and I wanted to do something beautiful to take her place. I didn't want to be a senior citizen. I wanted to stay young, so I turned back to youth. It was a defiance of old age." He also said he was trying to come to terms with the death of his brother and to tell the truth to himself about his brother's life and their reationship.

He had us return that evening for a drink and more conversation. He had us back the next afternoon to hike with him up into the mountains to see the glacier that feeds the Big Blackfoot River that runs through the valley between the Swan and Mission ranges, through his life, and through the stories. He had us stay for dinner and didn't send us away until late into the night. I think he saw my envy of his career, his book, the integrity of his life. I think I saw his envy of my youth and health, my life that far without major pain or loss, and perhaps of a young man and woman traveling across the country together, camping out of the back of a pickup truck. He gave me just enough of what I wanted for my interview and just what I needed for myself.

He gave me a glimpse of a proud man, struggling with growing old, working hard to find the words to say what he believed to be true about his own experience of life, and fighting to find out whether his own story made sense. "When I was 65," he said to me, "I went into my bedroom and said to myself, 'You're 65. Don't take any crap from anyone.' This business about identity being a crisis only for the young is a bunch of nonsense. If you re worth your salt, it's a problem all your life. I'm more concerned now about who I am than I ever was." Late that night, as I walked back to where we were camped on the beach, I carried with me the sense that I'd seen and heard some answers to questions I was only dimly aware of posing to myself, and part of what I was learning was that finding clear answers might be neither possible nor desirable. It was the asking and working at it that counted. And even then, there was more than effort and good intentions to reckon with. In the book, the narrator's father says that "all good things trout as well as eternal salvationcome by grace and grace comes by art and art does not come easy." Maclean was a master of the art of teaching, although he told me that the best advice he ever got about how to face a classroom was to change his suit and tie fairly often. He still wasn't sure, Maclean said, whether he should have been a professor, a forest ranger, or a smokejumper. Now he was working hard at being a storyteller. He'd made his choice as a young man, and the book was a kind of a substitute, an offering to himself and the memory of his wife, for the life he didn't choose to live.

Since meeting him, I'd been afraid he wouldn't live long enough to finish the next book he was working on, the story of some smokejumpers killed in 1949 fighting an infamous fire near Helena, Montana. After all, A River Runs Through It was more than 70 years in the making. The obituaries say that the new story, Young Men and Fire, is being considered for publication. They also say that Robert Redford has been interested in making a movie of the first book, which earned Maclean the attention of the fiction judges for the Pulitzer Prize (the prize committee overruled them for some reason and didn't award a prize in fiction that year). Several universities and colleges, including Dartmouth, also took notice and awarded him honorary degrees. I wish I knew how Maclean felt and what he said on coming back to Hanover in 1987, his first visit since departing from the English Department in 1926, for that award. It was the June before I came back to work as a dean, so I missed seeing him again. Maclean had told me he'd been unhappy during his two years teaching in Hanover, partly because "I've always made a point of being insolent; at Dartmouth I couldn't." On the other hand, he attributed much of his success as a teacher to the examples and influence of teachers he encountered here.

When I left the Alumni Magazine the second time—to attend graduate school, study religion, and pursue a career at a college or university instead of with a newspaper or magazine—the editor gave me a fly rod. The book and the rod continue to haunt me. They promise more than I've been able to attain. They remind me that it is as hard to find words as to catch fish. The good ones, if they strike at all, always seem to get away, and most of the rest aren't worth keeping. Those gifts remind me of books not written, fish not caught, dreams not realized, and lives not lived. But they also are a kind of consolation. Despite what we tell ourselves at some times in our lives, and despite the burden that too many of us lay on our children, you can't do or be good at everything, at least not all at once. You pick something, sometimes without the benefit of certainty or overwhelming conviction, and you do your best. You live with the choices you make, but it is never too late to make a choice. The end of the story doesn't have to be evident at the beginning. "What I remember are the moments when I saw my life taking on shapes and patterns," Maclean told me. "Life takes on designs that aren't visible until they're pointed out by a storyteller. The designs are part of something bigger, although I'd hesitate to say what."

BEFORE DAN NELSON TOOKhis cuirent job as dean ofDartmouth's upperclassstudents, he edited ClassNotes at the Alumni

Magazine, got a Ph.D.in religion, and taught atSt. Paul's Academy. Buthis best preparation maybe his experience as anoutdoorsman. He nowraces canoes with Assistant College Counsel

Sean Gorman '76, ownsa camp in Maine, andleads freshman trips. Abetter writer than fisherman, he is working tocorrect the imbalance.

Those giftsremind meof books notwritten, fishnot caught,dreams notrealized, andlives not lived.But they alsoare a kind ofconsolation."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureZ-Man Covers The War

February 1991 By Robert Eshman '82 -

Feature

FeatureOUR PASSIONATE PREFERENCE

February 1991 By Joseph D. Mathewson '55 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryNow For The Hard Part

February 1991 By Jay Heinrichs -

Feature

FeatureWHO OWNS DARTMOUTH?

February 1991 By Joe Boldt '32 -

Feature

FeatureIs Harvard Becoming More Like Dartmouth?

February 1991 -

Feature

FeatureWe asked some students: WHAT ONE THING WOULD YOU CHANGE ABOUT DARTMOUTH?

February 1991

Dan Nelson '75

-

Article

ArticleThe American Forum

January 1976 By DAN NELSON '75 -

Article

ArticleWarm Memories, Cold Pleasures

February 1976 By DAN NELSON '75 -

Article

ArticleIn Defense of Prejudice

April 1976 By DAN NELSON '75 -

Feature

FeatureThanks to Daniel Oliver, A Gathering of Lovers

May 1976 By DAN NELSON '75 -

Article

ArticleNeeded: More Misfits

June 1976 By DAN NELSON '75 -

Books

BooksTime and the Rivers

March 1979 By Dan Nelson '75

Features

-

Feature

FeatureCOMMENCEMENT 1968

JULY 1968 -

Feature

FeatureBibliographical Branding Irons

November 1976 By DAVID WYKES -

Feature

FeatureThe Silver Fox

Jan/Feb 2010 By EDWARD G. WILLIAMS ’64 -

Feature

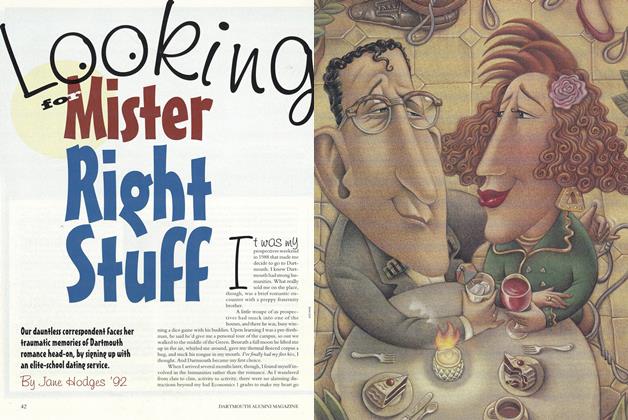

FeatureLooking for Mister Right Stuff

Novembr 1995 By Jane Hodges '92 -

Feature

Feature"Love in a Cold Climate" and Other Cures for the Winter Blahs

JANUARY/FEBRUARY • 1987 By Lee Michaelides -

Feature

FeatureNaming the Animals

OCTOBER 1996 By Robert Pack '51