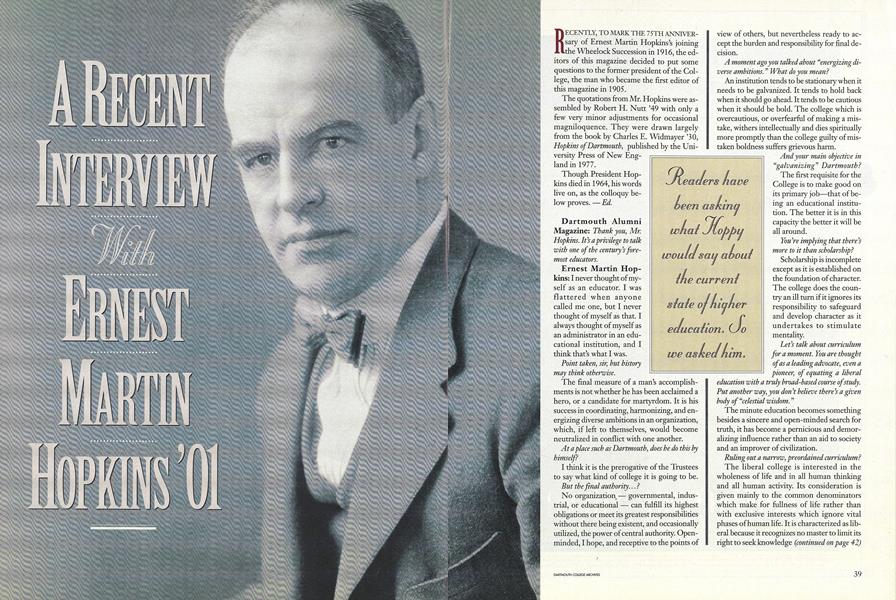

Recently, to mark the 75th anniversary of Ernest Martin Hopkins's joining the Wheelock Succession in 1916, the editors of this magazine decided to put some questions to the former president of the College, the man who became the first editor of this magazine in 1905.

The quotations from Mr. Hopkins were assembled by Robert H. Nutt '49 with only a few very minor adjustments for occasional magniloquence. They were drawn largely from the book by Charles E. Widmayer '30, Hopkins of Dartmouth, published by the University Press of New England in 1977.

Though President Hopkins died in 1964, his words live on, as the colloquy below proves. Ed.

Dartmouth AlumniMagazine: Thank you, Mr.Hopkins. It's a privilege to talkwith one of the century's foremost educators.

Ernest Martin Hopkins: I never thought of myself as an educator. I was flattered when anyone called me one, but I never thought of myself as that. I always thought of myself as an administrator in an educational institution, and I think that's what I was.

Point taken, sir, but historymay think otherwise.

The final measure of a man's accomplishments is not whether he has been acclaimed a hero, or a candidate for martyrdom. It is his success in coordinating, harmonizing, and energizing diverse ambitions in an organization, which, if left to themselves, would become neutralized in conflict with one another.

At a place such as Dartmouth, does he do this byhimself?

I think it is the prerogative of the Trustees to say what kind of college it is going to be. But the final authority... ?

No organization governmental, industrial, or educational can fulfill its highest obligations or meet its greatest responsibilities without there being existent, and occasionally utilized, the power of central authority. Openminded, I hope, and receptive to the points of view of others, but nevertheless ready to the burden and responsibility for final decision.

A moment ago you talked about "energizing diverse ambitions." What do you mean ?

An institution tends to be stationary when it needs to be galvanized. It tends to hold back when it should go ahead. It tends to be cautious when it should be bold. The college which is overcautious, or overfearful of making a mistake, withers intellectually and dies spiritually more promptly than the college guilty of mistaken boldness suffers grievous harm.

And your main objective in"galvanizing" Dartmouth?

The first requisite for the College is to make good on its primary job—that of being an educational institution. The better it is in this capacity the better it will be all around.

You're implying that there'smore to it than scholarship?

Scholarship is incomplete except as it is established on the foundation of character. The college does the country an ill turn if it ignores its responsibility to safeguard and develop character as it undertakes to stimulate mentality.

Let's talk about curriculumfor a moment. You are thoughtof as a leading advocate, even apioneer, of equating a liberaleducation with a truly broad-based course of study.Put another way, you don't believe there's a givenbody of "celestial wisdom."

The minute education becomes something besides a sincere and open-minded search for truth, it has become a pernicious and demoralizing influence rather than an aid to society and an improver of civilization.

Ruling out a narrow, preordained curriculum?

The liberal college is interested in the wholeness of life and in all human thinking and all human activity. Its consideration is given mainly to the common denominators which make for fullness of life rather than with exclusive interests which ignore vital phases of human life. It is characterized as liberal because it recognizes no master to limit its right to seek knowledge and no boundaries beyond which it has not the right to search. Its primary concern is not with what men shall do but with what men shall be.

Which is to be fully knowledgeable about all human thinking, all human activity?

No man can know all things. No man can ever foretell what things it will in the immediate future be most important to know. Consequently, the desirable results are that he shall acquire facility in learning easily, the will to learn accurately, and the taste for learning continuingly.

So, the central aim of the liberal arts college is... ... to develop a habit of mind rather than to impart a given context of knowledge. It is even more a responsibility of the liberal college to elevate the mind of man than to enlarge or sharpen it.

And that doesn't change as times change?

The rigidly correct point of view of one day has been too often proved the handicap of a succeeding day for me to be willing to see the College become dogmatic about anything except the fundamental obligation of men to live in accord with the general interest, and the enduring responsibility upon the individual to recognize that he is, in due proportion, his brother's keeper.

But that doesn't mean shared opinions?

It would be unfortunate for the country to have all of its citizens have a common view. The whole of my theory in regard to education is that the different philosophies of life should recognize the presumable integrity and value of other philosophies, and that men should interest themselves to find out what of possible value may lie in theories diametrically opposite to their own.

That makes you sound like a card-carryingeclectic.

It requires a tolerance and an openness of mind which shall not be passive and futile, but active and dynamic.

It also sounds as though we're talking about educating generalists rather than specialists. In fact,you yourself used to quote an executive at the ChaseBank as saying narrow practicality is self-defeating and that if colleges sent out graduates with agood general education and an inquiring mind, thebusiness world would quickly train them. Any reason to change your mind?

I would not underestimate the value of the so-called practical courses, but grave mistake is made by him who forgoes the lifelong enjoyment of the cultural courses. It is proper that we study practical affairs. However, no opportunity should be lost for securing those contacts that give access to the great and eternal values of life.

You don't want to turn, out professionals? I am a thorough and unmitigated bigot on the subject of overprofessionalism. One of the great evils in our civilization is that mankind almost invariably looks at the problems of society through the lenses of his professional connection. Today the world is handicapped even more by lack of men with sense of proportion and sense of the relationship of one phenomenon of life to another than by lack of erudition in specialized branches of knowledge. Ignorance of the relationships of knowledge may be found as evident and as dangerous among those learned in specialized fields as among those who are ignoramuses in all fields.

Perhaps an example of your desire to broaden young mindsbeyond the traditional and narrow was your planning, duringWorld War II, of a postwar curriculum that would give moreattention to geo-politics and especially to Oriental languages andthe Far East. That was a fairly prescient idea designed to... ... open our minds, rechannel our thinking, understand the world in which we live. Which should be?

A brave, clean world where all men of whatever race or whatever color should be free to live their own lives, think their own thoughts, dream their own dreams.

So, you'd expose undergraduates to any and all viewpoints,however strange or controversial?

I know of no man and no interest I would not present if it would stir up the minds of the undergraduates. Open-mindedness and the ability to think are, I believe, among the most cherished aims of the liberal college, and the greatest need of the hour. It is nonsense to think you are going to train people to be good Americans by withholding facts, or by presenting only one side of the case.

Which seems to call for an equally eclectic faculty. The strength of a college is essentially the strength of its faculty. If the faculty is strong, the college is strong. If the faculty is weak, the college is weak. Plant, financial resources, administrative methods, alumni enthusiasm and loyalty, are but accessory to the getting and holding of strength at this point.

Isn't there some risk that a strong faculty mayinclude some, well, troublemaking iconoclasts?

I do not want Dartmouth served by a tongue-tied or thought-repressed faculty, who stand in fear of losing their positions if they give expression to their convictions in regard to any subject upon which they are qualified to have an intelligent opinion. An individual does

not lose his rights to personal opinion or his privilege to an expression of these by becoming an officer of the College. I think too much of Dartmouth College to see her demeaned by yielding to pressure on this point. The whole spirit of Dartmouth College, even when interpreted through the context of modern conditions, is a challenge to develop original thought and to do intelligent pioneer work, to ignore convention if it becomes restrictive, and to avoid standardization if it becomes entangling.

Sounds as though you don't subscribe to "the more thingschange, the more they remain the same."

New times bring new conditions, and the techniques of educational method must keep pace with the changing status of the transforming world in which we live. The undergraduate

of today stands upon the threshold of a world whose problems would have staggered the imagination of generations past.

Let's talk about the student. Not long after youbecame president you originated the idea of "selective admissions," a fairly radical concept for thetime which went beyond a measurement of a candidate's intellectual capacity to include character,wide interests, and performance in school activities.Once again eclecticism. Why?

An undergraduate gets a considerable part of his education from association with his fellow students, and the more broadly representative your undergraduate body, why the better your educational process.

Doesn't that imply the need for more maturityand experience than the typical high school graduate is likely to display ?

The method of the educational institution in its search for truth calls for diversity in points of view and emphasis upon all things capable of stimulating the student's thought. Outside opinion to the contrary, the American college undergraduate is as competent to determine between reality and fallacy, between truth and error, between sincerity and hypocrisy, as he will be at any later time.

Experience suggests he or she often holds strongopinions on issues that can polarize a campus.

The very fact that opinion is so definitely divided among the students is in itself, I think, a far better effect than could have been accomplished by something in which everyone was agreed.

Even ifthis takes the form of obstreperous expression in print? All in all, there is less detriment to the College in letting its publications entirely alone and allowing them to go their individual ways than there is in any attempted censorship. This is not a matter of theory, but is plain practice and has been proved out time and time again in one college or another. I do not feel that it is right in principle, or wise in policy, for the administration to interfere in matters of this sort or to lay the hand of authority upon the expression of opinion.

You're in favor of giving the student pretty much free rein? It is easy to say to an undergraduate that the institution is established and maintained for his benefit. If, however, this is interpreted to mean that the college lives to meet his personal convenience, or to enhance his personal suecess as apart from the needs of society and his ability to contribute to them wrong is done the man, and the college trust has been maladministered.

We're reminded that back in 1928 during a speech aboutstudent complainers—you said, "In place of any discussion ofwhat undergraduates might do to help their college.. ... we find the tiresome reiteration of what the college ought farther to do for the undergraduate.

And alumni seem to complain, as well.

The objective of the American college, it seems to me, is to prepare people to enter the society of their time and enhance its intellectual and moral standards. If the purpose of the American college is to produce alumni, it is no less the purpose of the college to retain the interest and the intelligent support of alumni. The value of the alumni to the College is almost wholly a matter of whether they can be made to make their interest and solicitude intelligent. Or not.

And when it's "or not".. ?

If alumni are pestiferous and troublesome, it is because they are not given sufficient knowledge of what the College is about. I do have an overpowering inclination about once in so often to do something to indicate to some of our alumni that a man does not bind himself body and soul to drab neutrality on all subjects even if he does accept a college presidency.

You have also said that the value of alumni toan institution is in direct proportion to their understanding of the changing responsibilities ofhigher education. Can you elaborate on that theme?

Such strength as the American college lacks it lacks, in the main, because of the too great confinement of interest among alumni to the college of their undergraduate days. Many a man, through lack of opportunity for anything else, draws all the inspiration for his enthusiasm for his college from his memories of life when an undergraduate, and feeds his loyalty solely upon sentimental reverence for the past. The emotional alumnus, harking back only to undergraduate days, is an incomplete alumnus of minimum value at best and a positive detriment at worst.

And when all of Dartmouth's constituencies are workingtogether. . ?

A friendly observer of the College said to me that nobody could understand Dartmouth who didn't recognize that it was not simply another educational institution but that it was likewise a religion. Personally I believe very strongly that a third aspect is important for us to recognize—that it is a family. And at times when that has been most evident, most existent, the College has fared best.

Thank you, President Hopkins.

Readers havebeen asking what Hoppy would say aboutthe currentstale of higher education, So we asked him.

"Scholarshipis incompleteexcept as if isestablished onthe foundationof character,

"I know of no man and no interest I would not present if it would stir up the minds of the undergraduates."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

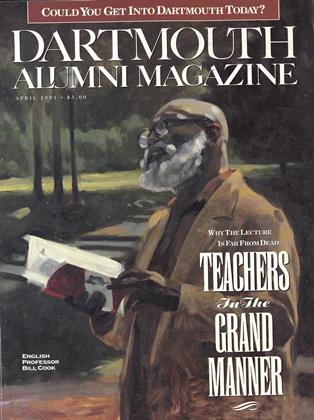

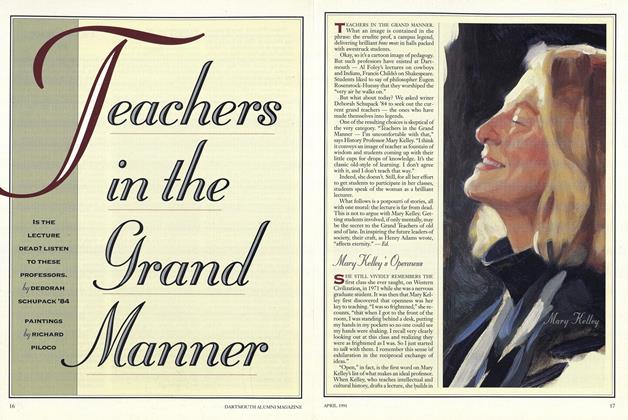

Cover Story

Cover StoryTeachers in the Grand Manner

April 1991 By DEBORAH SCHUPACK '84 -

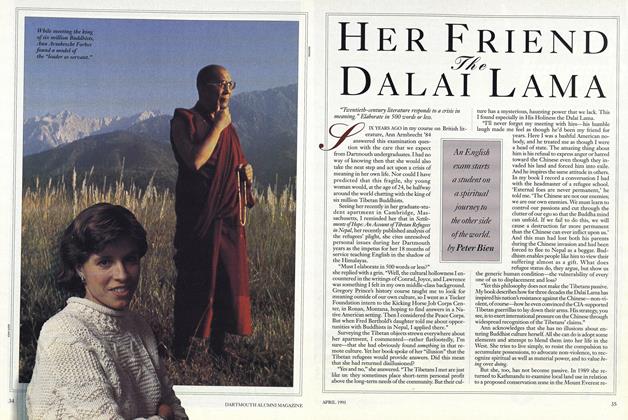

Feature

FeatureHer Friend the Dalai Lama

April 1991 By Peter Bien -

Feature

FeatureSTEVE KELLEY IN TWO ACTS

April 1991 By ROBERT ESHMAN '82 -

Feature

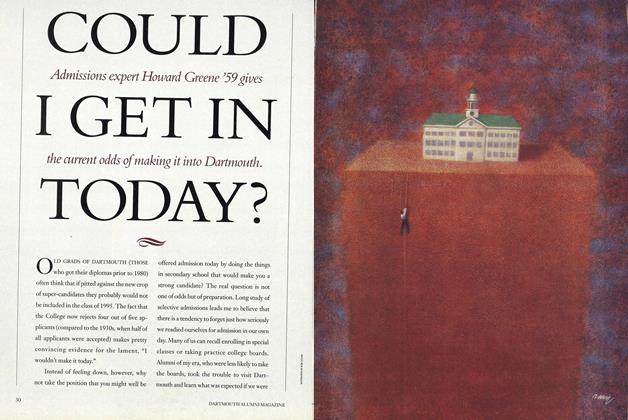

FeatureCOULD I GET IN TODAY?

April 1991 -

Feature

FeatureDisengagement

April 1991 By John Sloan Dickey '29 -

Article

ArticleDR. WHEELOCK'S JOURNAL

April 1991 By E. Wheelock

Features

-

Feature

FeatureThe Financial Road Ahead

April 1962 -

Feature

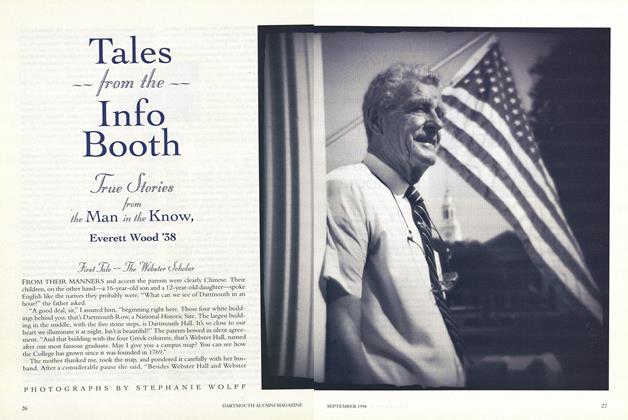

FeatureTales from the Info Booth

SEPTEMBER 1994 -

Feature

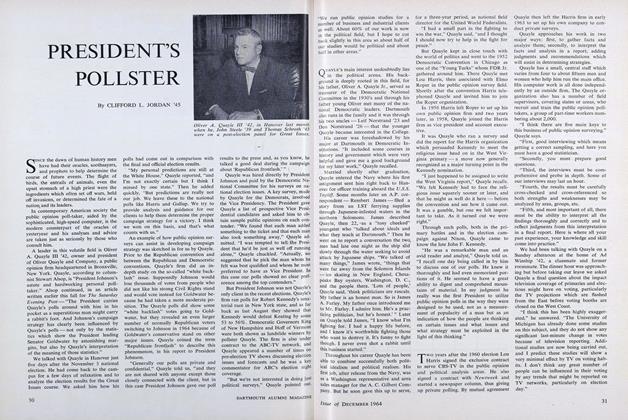

FeaturePRESIDENT'S POLLSTER

DECEMBER 1964 By CLIFFORD L. JORDAN '45 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryGETTING IN

MAY 1997 By FRANK D. GILROY '50 -

Feature

FeatureTerrorism and the Niceties of Justice

MAY 1982 By Joseph W. Bishop Jr. -

Feature

FeatureThe Bearing of the Green

FEBRUARY 1969 By Mary B. Ross ('38)