Three Analogies that Dartmouth's Chemistry Department Uses to Describe the Delicate Balance Between leaching and Research:

Albert W. Smith Professor of Chemisry Emeritus Walter H. Stockmayer

"A Knife's Edge"

Albert W. Smith Professor of Chemistry David Lemal

"A Potentially Unstable State."

Professor of Chemistry Charles Braun

IN DARTMOUTH'S CHEMISTRY DEPARTMENT they talk about spin-spin coupling and electronically excited states, but their vision is surprisingly humane. The department's guiding light, Walter H. Stockmayer, one of the nation's most distinguished polymer chemists, is called "Stocky" by nearly everybody.

He seems to have a thing for chickens, by the way. And he has earned the envy of novelist Kurt Vonnegut. Who says chemistry is all beakers and test tubes?

"We have fun here," says Professor Charles Braun. "And we all work 70 hours a week."

Dartmouth's Chemistry Department is far from being the nation's largest or best-funded, but it seems to have found an unusually successful formula—fusing classroom learning and lab research—for turning undergraduates into scientists. "Unlike other chemistry departments of the Ivy League, you have raised real chemists as opposed to premeds," says University of Wisconsin chemist Hyuk Yu. "The principal reason is the way your faculty has involved itself with undergraduate research."

Ever since President John Sloan Dickey '29 began a push for the "teacher-scholar" in the forties and fifties, the College has debated with itself how to sustain the balance between research and teaching. The ideal would be if the two served as catalysts for each .other. Chemistry now seems to come closest. "It is exemplary of what Dartmouth is trying to do as an undergraduate institution," says Associate Provost Bruce Pipes. "They really put themselves into the instruction of undergraduates, while also being really strong in research." Moreover, adds Pipes, "They do this in an extremely collegial way. I don't know if they sign pacts in blood or what." Dartmouth's chemists do not seem to maintain the competitiveness and wary silences that stalk many other chemistry departments. Their colleagues are their friends. Undergraduates assist in research, often making publishable contributions of their own.

Who is responsible for this personal chemistry? People in the department point to Stockmayer, Albert W. Smith Professor of Chemistry Emeritus.

"Stocky epitomizes the character of the department," asserts organic chemist Gordon Gribble. "People who have come after him have latched onto his approach and personality."

"He teaches about science, but also about being a human being doing science," says Russell Hughes, the department's chairman. "He reminds us that science is a purely human activity." Hughes recalls that when he first came to Dartmouth 15 years ago, "it was clear that I was expected to become an excellent teacher. I was expected to become what the others were."

Here's an experiment. Try asking any of Dartmouth's chemistry professors about the department. You'll find that no matter how distinguished they are in their own subfields, they inevitably will say, "Talk to Stocky."

But the thing is, Stocky would rather talk about them. About Assistant Professor Jane Lipson and her polymer research, for example.

Or about Professor Gordon Gribble, who sees the work of synthesizing organic molecules as "creative, almost painterly," and who wins awards for his fruit wines.

Or about Professor Russell Hughes, a Welsh organometallic chemist who says he was "enchanted" when, as a graduate student, he made his first entirely new chemical compound.

Or about Professor Dean Wilcox, who, with the help of graduate and undergraduate assistants, has synthesized a small liver protein that binds and removes toxic metals in humans and who suggests that similar metalbinding molecules might be used as an "environmental sponge" to scavenge poisons from soil and water.

Or about Professor Charles Braun, a passionate windsurfer who has made himself popular among students with classroom demonstrations involving balloons and bubbles, and who uses a U.S. Department of Energy grant to study light-driven molecular reactions—research which could someday lead to the development of moleculebased solar batteries.

Or about Sam Conway, a graduate student who, after deciding to study organic chemistry at Dartmouth, leaped into Gordon Gribble's arms yelling, "Daddy!" (Gribble set Sam down in his office to talk about projects.)

Or about Professor Karen Wetterhahn's investigation of links between chromium and cancer, which in the past year enlisted an undergraduate presidential scholar, a freshman intern from a new program called Women in Science, a sophomore chemistry major, and two seniors who were doing honor theses.

Stocky would rather talk about any of these others than about himself. Yet if anyone in the department has a right to be a prima donna, his colleagues say, it's Stocky. He is an expert on the statistical mechanics of polymers, a pioneer in plastics. In 1987 he received the National Medal of Science. He even ended up in a novel. In Breakfastof Champions, Kurt Vonnegut writes that Stockmayer is "a distinguished physical chemist, and an amusing and useful friend of mine. I did not make him up. I would like to be Professor Walter H. Stockmayer. He is a brilliant pianist. He skis like a dream."

But self-promotion is not in his blood. Reminded of his reputation for inspiring other chemists, Stocky demurs, "Oh, I don't know, I'm sort of a senior role model I guess." He insists he is only carrying the torch for those who came before him, such as the late John Wolfenden, a teacher who steered students toward research.

It was Wolfenden who helped persuade Stockmayer to come to Dartmouth from MIT in 1961. Believing that his best research was behind him, Stocky wanted to concentrate on teaching undergraduates while enjoying the White Mountains and professional association with his friend Wolfenden. Stocky's reputation followed him, however. A Cal Tech graduate named John Hearst (now a professor at Berkeley), intent on studying the kinetic theory of macromolecules, sought him out as an advisor even though there were no graduate programs in the arts and sciences at Dartmouth. Stockmayer took him on, and in the process revitalized his own research. In 1966 he helped develop the new chemistry graduate program established by President Dickey. Over the years Stockmayer effected a balance between teaching and research which has come to characterize the department itself. "It's not 50-50 on any given day," he says, "but a healthy alternation."

So far, four Dartmouth professors have won the Chemical Manufacturers Association's Catalyst Award for outstanding teaching. Charles Braun won it this year. David Lemal, Walter Stockmayer, and John Wolfenden won it previously. The success of undergraduate majors attests to teaching quality as well; three of them received 1991 National Science Foundation fellowships for graduate studies. The Chemistry Department itself has been awarded funding from the NSF to provide stipends, housing, and lab materials to students doing research in the summer. The department's undergraduate teaching sets the tone for the graduate program. In order to nudge its Ph.D. candidates towards academic careers, the department plans to institute a teaching skills tutorial for first-year grad students. Not that they need a lot of nudging. "Many of us want to be teachers," says Angela Kowalski 'G.

Both teaching and research should get a boost with the September 1992 opening of a $24 million dollar chemistry facility. Burke Hall—named after Walter Burke '44, president and treasurer of the Sherman Fairchild Foundation—will provide needed lab and office space and state-of-the-art safety features such as individual fume hoods. And it will feature innovations designed to encourage undergraduate research. For instance, glassed-in lab areas resembling fish tanks will allow students to write up notes, study, or eat away from fumes while keeping an eye on experiments. The building will also have a low-tech feature that is sorely lacking in the old facilities: a lounge. This was something especially requested by a department that obviously likes to hang together.

No doubt Stocky will be making the building's rounds. It is hard to tell that he has had an "emeritus" dangling off the end of his title for 12 years now. He still teaches the occasional class, and he only recently closed his lab in order to concentrate on writing up old research notes and catching up on correspondence. He continues as associate editor of the biweekly journal Macromolecules, which has sometimes carried a column by a mysterious Dr. Waldemar Silberszyc (pronounced "Silvershits" if you know your Polish) of the N.E. Poultry Anal. Institute. Stocky's penchant for poultry has become departmental legend. Rumor has it that students once let a live chicken loose in his class. When the department threw him a 70th birthday roast a few years back, his colleague Hughes arrived dressed, appropriately, as a chicken. Unruffled, Hughes explains, "There's probably not much we wouldn't do for Stocky."

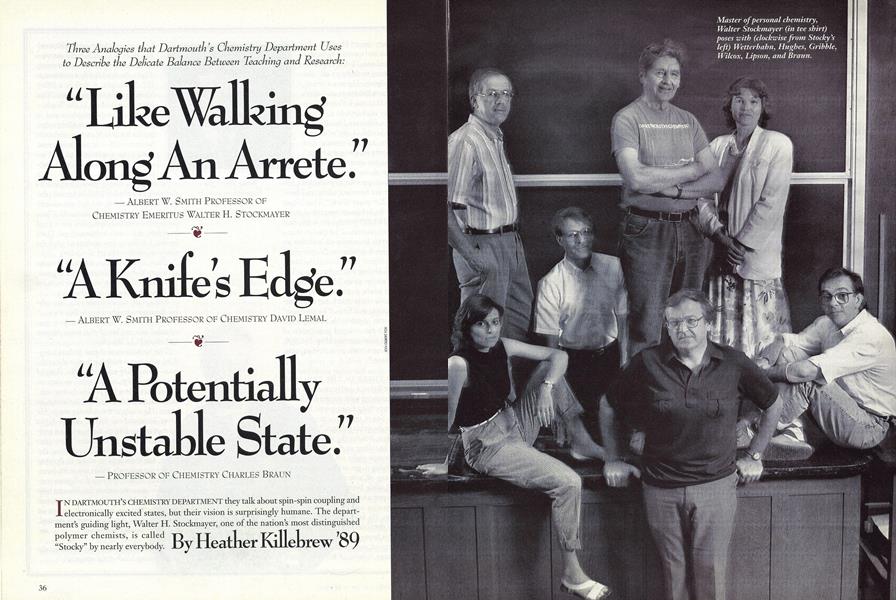

Master of personal chemistry,Walter Stockmayer (in tee shirt)poses with (clockwise from Stocky's left) Wetterhahn, Hughes, Gribble,Wilcox, Lipson, and Braun.

"I didn't make him up," KurtVonnegut writes of Stocky in anavel. The book contains thestructure of a plastic molecule.

Heather Killebrew is this alumni news editor.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureMENCKEN UNBOXED

October 1991 By ROBERT SULLIVAN '75 -

Feature

FeatureHONEST TO GOD ACCOMMODATION

October 1991 By JAMES O. FREEDMAN -

Feature

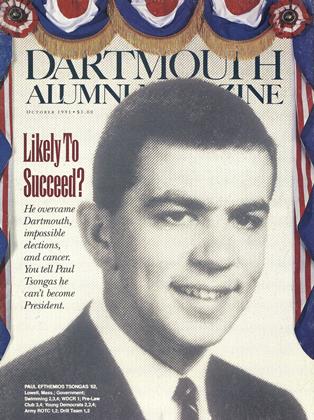

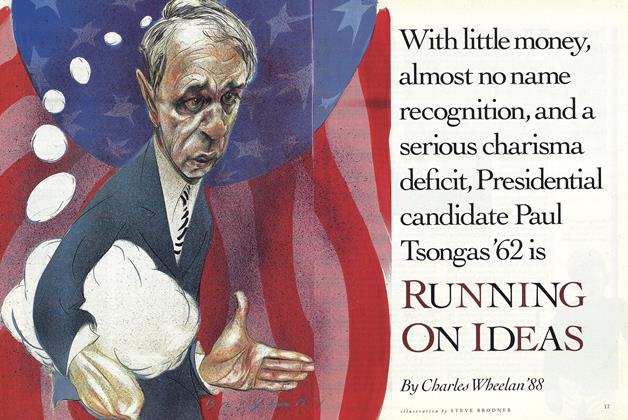

FeatureRUNNING ON IDEAS

October 1991 By Charles Wheelan ’88 -

Feature

FeatureThe Masked Stork

October 1991 By William DeJong '73 -

Article

ArticleDR. WHEELOCK'S JOURNAL

October 1991 By E. Wheelock -

Class Notes

Class Notes1988

October 1991 By Chuck Young

Heather Killebrew '89

-

Article

ArticleGeorge Washington on Trial

APRIL 1991 By Heather Killebrew '89 -

Article

ArticleHat-Trick

April 1993 By Heather Killebrew '89 -

Article

ArticleA Marketable Musical Philosophy: Fun

NOVEMBER 1993 By Heather Killebrew '89 -

Article

ArticleThe Landmark "Retires"

June 1995 By Heather Killebrew '89 -

Article

ArticleBut Seriously, Take My Career...

APRIL 1997 By Heather Killebrew '89 -

Article

ArticleDartmouth OuT O' DOORS

MAY 1997 By Heather Killebrew '89

Features

-

Feature

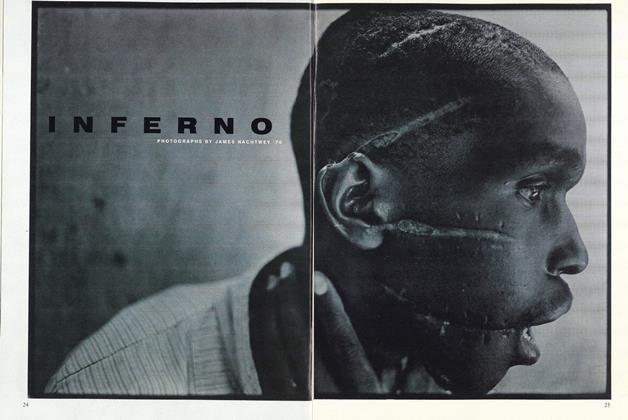

FeatureInferno

JUNE 2000 -

Feature

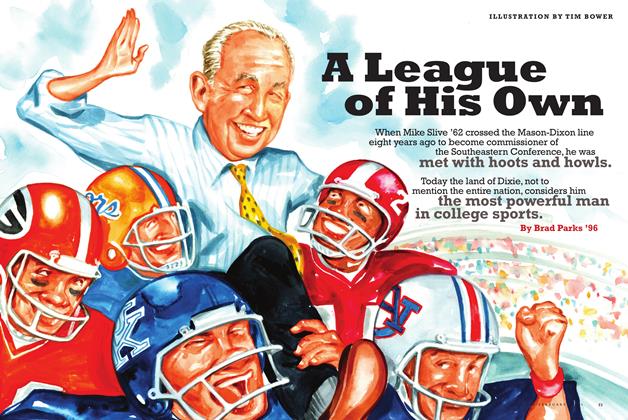

FeatureA League of His Own

Jan/Feb 2011 By Brad Parks ’96 -

Cover Story

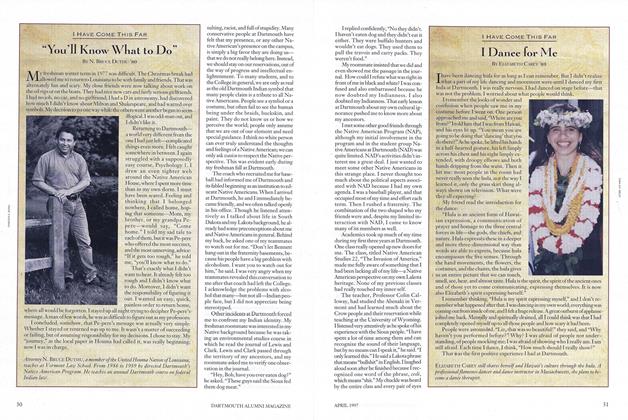

Cover StoryI Dance for Me

APRIL 1997 By Elizabeth Carey '93 -

Feature

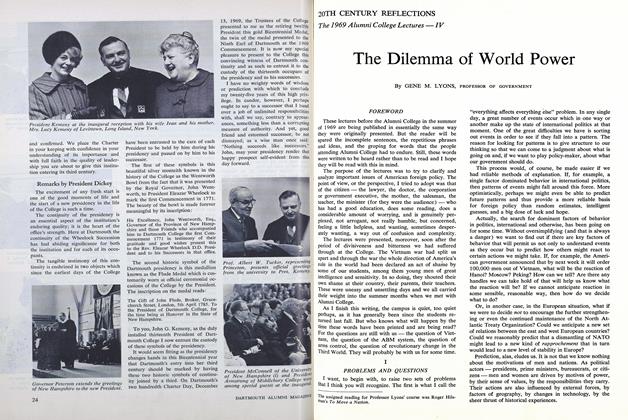

FeatureThe Dilemma of World Power

APRIL 1970 By GENE M. LYONS -

Feature

FeatureEight Graduates of Dartmouth Who Were First College Presidents

JUNE 1969 By John Hurd '21 -

Feature

FeatureEnd of a Golden era

APRIL 1982 By Shelby Grantham