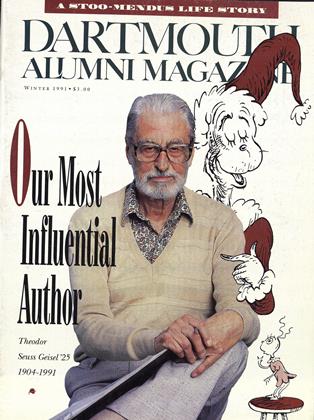

As the good Dr. Seuss, Ted Geisel '25 did more than influence the literary landscape. He made one from scratch,

I MUST HAVE BEEN FIVE. MAYBE SIX. IT must have been someplace in New England, because our family never vacationed anywhere else. We were at one of those Santa's Village or Storyland or Hansel & Gretel's places. We were in a witch's cottage, and the long-nosed witch was presiding from the other side of a boiling cauldron. The witch was saying: "Come on, little booooys! Trrrry and hook a fish!" I was standing there holding a stick with a piece of string and a huge hook attached. My brother was standing anxiously by my side. Floating upon the surface of the smoking water was a school of plastic fish. The idea was to finagle the hook into a fish's mouth, and to land the sucker. I finally accomplished this.

The witch freed the fish, turned it over and found the number 8 (or some such) inscribed upon its flat bottom. Nuuuumber Eight!!" she cackled, as if it were Satan's own favorite. She turned dramatically to the shelf behind her, and from basket Number 8 she pulled a book. "Heeeere you are boooys! You've won a cat! Witches love cats!!"

We took our book and departed for sunnier amusements. The book was The Cat in the Hat by Dr. Seuss. Neither my brother nor I had ever heard of either this cat or that doctor. During the next couple of years, however, the book was among our favorite things. The cat book grew dog-eared like no book either of us has owned since. We could read it ourselves, you see, and as Robert Frost once said about lightly traveled roads, that made all the difference.

I must have been five.

GROWN NOW, and grown into a job where I talk to people and tell others what they've said, I approached the kindly editor of this magazine about a year ago and asked if I could "do Seuss." The editor had a salient bit of foreknowledge that Seuss and Ted Geisel, class of '25, were one and the same and so he said, sure, by all means, "Do Seuss!" Random House, the doctor's publisher for lo these many years, obligingly sent along a packet of clippings in a bright red folder with the familiar "Dr. Seuss" scroll blazing across it. (Geisel, having sold some 200 million books for Random House in the last half-century, rated his own folder.) The company also forwarded a letter to Geisel for me. Back, and promptly, came a note from La Jolla, California. Running down the left side of the notepaper was the feline itself, the Cat, in its hat. What the Cat was saying to me in the balloon that drifted above its hat was, "Dear Bob." The note continued, after some brief familiarities: "Problem is, I'm just too pooped and worked-on by doctors to help you at all right now. And there's just no way to give you an honest hunch on when, if at all, I'd be able to. I've foolishly agreed to turn my latest book into a full-length musical for Tri Star, and although I'm doing it in La Jolla, not Hollywood, God knows what complications are ahead. I just can't, as much as I'd like to, give you the cooperation you'd need. Not just for now. If things change, I most certainly will let you know.

"With all best of best good wishes, "Ted."

I had already started reading through the Random clips, and so I knew some of what Geisel alluded to. In the last several years he had suffered a heart attack and had undergone no fewer than five cataract operations. The operations had restored his color vision, and thank goodness for that since he was an artist to whom color, both verbal and primary, was essential. Meanwhile, Tri Star studio had contracted to bring Oh, the PlacesYou'll Go!, Geisel's bestselling valedictory address, to the screen.

As I smiled at his genial note, I imagined Geisel writing it. He would be sitting in his study, which is just a few paces from his bedroom in a Spanish-style stucco house atop Mount Soledad, a eucalyptus-studded hillock that rises 800 feet from the Pacific shore. The house had originally been built as a watchtower Geisel and his first wife, Helen, moved to California in the forties when Ted was doing some earlier Hollywood work, and they moved into the watchtower in '47.

Geisel would be sitting there, felt-tip in hand, gazing out the large plate-glass window at his hundredmile view of the Pacific, puzzling how to politely demur to this billionth request for a billionth interview. He would look out over his rock garden, down the hillside to the beach and to the surfers below. He would look down at the pleasant grin of his famous cat on the stationery. "Problem is... "

I bothered Geisel with one more note and ascertained that I could, in fact, proceed with this project, even without an interview. On a second piece of Cat-in-the-Hat note-paper he assured me that talking to his friends would be perfectly fine. "Good luck with it!" he wrote. That marked my last correspondence with Ted Geisel.

All of that is merely sad prelude now, for Geisel, as is widely known, died at his home on the night of September 24. I was particularly struck by the news since I was only just then, after a long time at it, finishing my doing of Seuss.

Before we set forth upon the story of Geisel's long and now-finished life, I feel compelled to add a last bit about my researches. I've relied on the work of a hundred journalists who've done Seuss before me. A thorough story by E. J. Kahn in The New Yorker served as source material. So did a top-notch interview with Geisel by then Baker Librarian, and now Librarian Emeritus, Edward Connery Lathem, which was published in the pages of this very magazine in 1976. Their good efforts helped.

I'd like to stipulate that no quote from Geisel is casually used. If there is no citation, then one of two things happened. Either I found the quote, in substantially the same form, in at least a few places. Or, alternately, I stumbled across utterances by Geisel that haven't been printed elsewhere. Either they were supplied to me by Geisel's friends, or they were uncovered in archives.

Sometimes, as you might expect, accounts have varied slightly. For instance, Geisel routinely explained the byline "Dr. Seuss" this way: He was a young man who had more grandiose goals as a novelist in mind when he sought to publish his first children's book in 1937. Therefore, he opted to save "Theodor Geisel" for this great-work-to-come, and used "the good Dr. Seuss" on "the brat book." Seuss was not only Geisel's middle name, it was his mother's maiden name and it was, thirdly, a pseudonym he had used off and on ever since his Dartmouth days. So calling himself "Seuss" seemed like a somewhat sensible thing to do.

Okay that much of the story remained pretty consistent in all accounts. But then Geisel usually added this punchline about the "doctor" bit: "My father sent me to Oxford to become a professor of English literature, and I figured I'd save him about $10,000 by not staying but just fixing the title there myself." Good joke, and one perhaps made better in the seventies and eighties when Geisel started saying he saved his dad "about $25,000." Well, inflation, of course. But, you see, it's a bit off.

Anyway, when I've found myself in doubt about which version of an anecdote to record, I flipped a coin. That is a method which, as you shall see, always worked pretty well for Dr. Seuss.

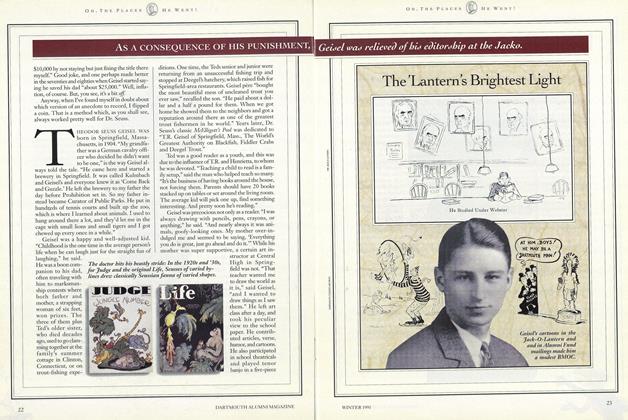

THEODOR SEUSS GEISEL WAS born in Springfield, Massachusetts, in 1904. "My grandfather was a German cavalry officer who decided he didn't want to be one," is the way Geisel always told the tale. "He came here and started a brewery in Springfield. It was called Kulmbach and Geisel's and everyone knew it as 'Come Back and Guzzle.' He left the brewery to my father the day before Prohibition set in. So my father instead became Curator of Public Parks. He put in hundreds of tennis courts and built up the zoo, which is where I learned about animals. I used to hang around there a lot, and they'd let me in the cage with small lions and small tigers and I got chewed up every once in a while."

Geisel was a happy and well-adjusted kid. "Childhood is the one time in the average person's life when he can laugh just for the straight fun of laughing," he said. He was a boon companion to his dad, often traveling with him to marksmanship contests where both father and mother, a strapping woman of six feet, won prizes. The three of them plus Ted's older sister, who died decades ago, used to go clamming together at the family's summer cottage in Clinton, Connecticut, or on trout-fishing expeditions. One time, the Teds senior and junior were returning from an unsuccessful fishing trip and stopped at Deegel's hatchery, which raised fish for Springfield-area restaurants. Geisel pere "bought the most beautiful mess of uncleaned trout you ever saw," recalled the son. "He paid about a dollar and a half a pound for them. When we got home he showed them to the neighbors and got a reputation around there as one of the greatest trout fishermen in he world." Years later, Dr. Seuss's classic McElligott's Pool was dedicated to "T.R. Geisel of Springfield, Mass., The World's Greatest Authority on Blackfish, Fiddler Crabs and Deegel Trout."

Ted was a good reader as a youth, and this was due to the influence of T.R. and Henrietta, to whom he was devoted. "Teaching a child to read is a family setup," said the man who helped teach so many. "It's the business of having books around the house, not forcing them. Parents should have 20 books stacked up on tables or set around the living room. The average kid will pick one up, find something interesting. And pretty soon he's reading."

Geisel was precocious not only as a reader. "I was always drawing with pencils, pens, crayons, or anything," he said. "And nearly always it was animals, goofy-looking ones. My mother over-indulged me and seemed to be saying, 'Everything you do is great, just go ahead and do it.'" While his mother was super supportive, a certain art instructor at Central High in Springfield was not. "That teacher wanted me to draw the world as it is," said Geisel, "and I wanted to draw things as I saw them." He left art class after a day, and took his peculiar view to the school paper. He contributed articles, verse, humor, and cartoons. He also participated in school theatricals and played tenor banjo in a five-piece jazz band. His favorite subject at Central was English composition, and he decided even before heading for Hanover that he would be either a writer or a teacher.

His dad had wanted him to go to Yale, but young Ted decided to head up, rather than down, the Connecticut River. "The reason so many kids went to Dartmouth at that particular time from the Springfield high school was probably Red Smith, a young English teacher. He was a real stimulating guy who probably was responsible for my starting to write," Geisel told Lathem in these pages 15 years ago. "His family ran a candy factory in White River Junction, I remember that. And I think when time came to go to college we all said, 'Let's go where Red Smith went.'"

Geisel arrived in the autumn of 1921, a friendly, lean, hawk-nosed kid. He immediately became a not-bad-but-not-great scholar, a renowned wit, a popular man on campus. In a natural continuation of his work at the Central High paper, he joined the jack-O-Lantern. It was the heyday of college humor, which is not necessarily to say the pinnacle. (Sample joke, as once remembered by Geisel: The First Chimney Sweep says, "Shall I go down first?" The second answers, "Soot yourself." Reader laughs HERE.) S.J. Perelman, Robert Benchley, James Thurber, Corey Ford, and Geisel were contemporaneously in college, and were inventing the mock-sophisticated non-sequitur comedy that would define such magazines as Judge, the first Life, and the cornier side of the nascent New Yorker. These raccoon-coated jazz-age wit wizards particularly the ones who could sell their best gags to New York-based publications, were campus stars of equivalent brightness to, say, tennis lettermen, if not footballers. It seemed, remembered Geisel once, "that all you had to do was say gin' and everybody would laugh."

Well, not everybody.

As a consequence of his punishment, Geisel was relieved of his editorship at the Jacko. The spring of '25 edition carried a suspiciously high number of unsigned articles, gags, and even cartoons. Moreover, there were sketches by several brand-new artists: "D.G. Rossetti '25," "T. Seuss" and one simply by "Seuss."

Perhaps the most important thing Geisel gained at Dartmouth was the sense of enjoyment he would derive forevermore from the act of literary creativity. Red Smith had planted the seed in Springfield, and English prof W. Benfield Pressey nurtured the bloom in Hanover. "My big inspiration for writing there was Ben pressey," Geisel remembered to Lathem. "He seemed to like the stuff I wrote." A rather pretentious avant gardest back then, as any college student might be, Geisel once did a book review of the Boston & Maine Railroad timetable. "Nobody in the class thought it was funny except Ben and me.

"Another guy who was a great encouragement was Norman Maclean, the Jacko editor preceding me. We had a rather peculiar method of creating literary gems. Hunched behind his typewriter, he would bang out a line of words. Then he'd say, 'The next line's yours.' And I'd supply it. This may have made for rough reading, but it was great sport writing." It's interesting, if not terribly enlightening, to note that the authors of two wildly different American fishing classics the fanciful McElligott'sPool and Maclean's contemplative ARiver Runs Through It once collaborated in this way.

At the Jacko, Geisel became fascinated by "the excitement of 'marrying' words to pictures. I began thinking that words and pictures, married, might possibly produce a progeny more interesting than either parent. It took me a quarter century to find the proper way to get my words and pictures married. At Dartmouth I couldn't even get them engaged."

In the summer of '25 Geisel worked for three weeks as an editorial-page writer for the Springfield Union, and managed to get it announced in the paper that he had won a Campbell Fellowship to study English lit at Oxford. Problem was, he hadn't actually won the thing yet, and he wouldn't. But his father, in order to preserve the family's honor throughout western Massachusetts, coughed up the dough for Ted to go to England.

"My tutor was A.J. Carlyle, the nephew of the great, frightening Thomas Carlyle. I was surprised to see him alive. He was surprised to see me in any form. I was bogged down with old High German and Gothic and stuff of that sort, in which I have no interest whatso- ever — and don't think anybody really should." During one particularly burdensome lecture by the Oxfordially named Professor Oliver Onions — Onions's pedantry having to do with the punctuation in KingLear, and how everyone since Shakespeare had simply, missed the point — Geisel took to doodling. A theretofore reticent blonde classmate looked over his shoulder and said, "That's a very fine flying cow." Indeed it was. Geisel, who always responded positively though self-effacingly to flattery, was smitten. The young woman was Helen Palmer, a New Jerseyite and fellow advanced- degree candidate. She became Geisel's friend, and from the first, his best critic.

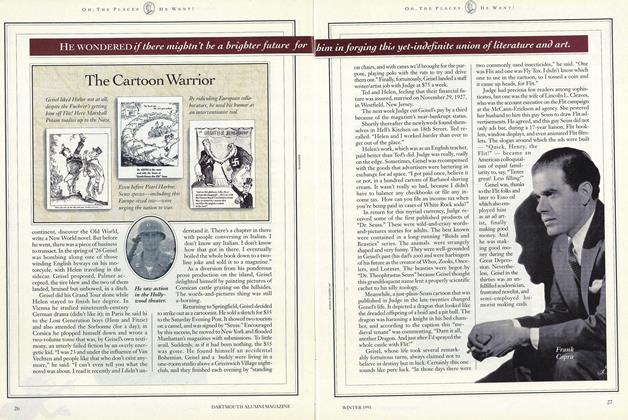

By school year's end, Geisel was ready to chuck Oxford entirely He wanted to go to-the continent, discover the Old World, write a New World novel. But before he went, there was a piece of business to transact. In the spring of '26 Geisel was bombing along one of those winding English byways on his motorcycle, with Helen traveling in the sidecar. Geisel proposed, Palmer accepted, the tire blew and the two of them landed, bruised but unbowed, in a ditch.

Geisel did his Grand Tour alone while Helen stayed to finish her degree. In Vienna he studied nineteenth-century German drama (didn't like it); in Paris he said hi to the Lost Generation boys (Hem and Fitzie) and also attended the Sorbonne (for a day); in Corsica he plopped himself down and wrote a two-volume tome that was, by Geisel's own testimony, an utterly failed fiction by an overly energetic kid. "I was 23 and under the influence of Van Vechten and people like that who don't exist anymore," he said. "I can't even tell you what the novel was about. I read it recently and I didn't understand it. There's a chapter in there with people conversing in Italian. I don't know any Italian. I don't know how that got in there. I eventually boiled the whole book down to a twoline joke and sold it to a magazine."

As a diversion from his ponderous prose production on the island, Geisel delighted himself by painting pictures of Corsican cattle grazing on the hillsides. The words-and-pictures thing was still a-borning.

Returning to Springfield, Geisel decided to strike out as a cartoonist. He sold a sketch for $35 to the Saturday Evening Post. It showed two tourists on a camel, and was signed by "Seuss." Encouraged by this success, he moved to New York and flooded Manhattan's magazines with submissions. To little avail. Suddenly, as if it had been nothing, the $35 was gone. He found himself an accidental Bohemian. Geisel and a buddy were living in a one-room studio above a Greenwich Village nightclub, and they finished each evening by "standing on chairs, and with canes we'd brought for the purpose, playing polo with the rats to try and drive them out." Finally, fortuitously, Geisel a staff writer/artist job with Judge at $75 a week.

Ted and Helen, feeling that their financial future was assured, married on November 29,1927, in Westfield, New Jersey.

The next week Judge cut Geisel's pay by a third because of the magazine's near-bankrupt status.

Shortly thereafter the newlyweds found themselves in Hell's Kitchen on 18th Street. Ted recalled: "Helen and I worked harder than ever to get out of the place."

Helen's work, which was as an English teacher, paid better than Ted's did. Judge was really, really on the edge. Sometimes, Geisel was recompensed with the goods that advertisers were bartering in exchange for ad space. "I got paid once, believe it or not, in a hundred cartons of Barbasol shaving cream. It wasn't really so bad, because I didn't have to balance any checkbooks or file any income tax. How can you file an income tax when you're being paid in cases of White Rock soda?

In return for this myriad currency, Judge received some of the first published products of "Dr. Seuss." These were wild-and-crazy words-and-pictures stories for adults. The best known were contained in a long-running "Boids and Beasties" series. The animals were strangely shaped and very funny. They were well-grounded in Geisel's past (his dad's zoo) and were harbingers of his future as the creator of Whos, Zooks, Oncelers, and Loraxes The beasties were begot by "Dr. Theophrastus Seuss" because Geisel thought this grandiloquent name lent a properly scientific cachet to his silly zoology.

Meanwhile, a just-plain-Seuss cartoon that was published in Judge in the late twenties changed Geisel's life. It depicted a dragon that looked like the dreaded offspring of a boid and a pit bull. The dragon was harassing a knight in his bed chamber, and according to the caption this "medieval tenant" was commenting, "Darn it all, another Dragon. And just after I'd sprayed the whole castle with Flit!"

Geisel, whose life took several remarkably fortuitous turns, always claimed not to believe in destiny but in luck. Certainly this one sounds like pure luck. "In those days there were two commonly used insecticides," he said. ' One was Flit and one was Fly Tox. I didn't know which one to use in the cartoon, so I tossed a coin and it came up heads, for Flit."

Judge had precious few readers among sophisticates, but one was the wife of Lincoln L. Cleaves, who was the account executive on the Flit campaign at the McCann-Erickson ad agency. She pestered her husband to hire this guy Seuss to draw Flit advertisements. He agreed, and this guy Seuss did not only ads but, during a 17-year liaison, Flit booklets, window displays, and even animated Flit filmlets. The slogan around which the ads were built

"Quick, Henry, the Flit!" became an American colloquialism of equal familiarity to, say, "Tastes great! Less filling!"

Geisel was, thanks to the Flit folks and later to Esso oil which also employed him as an ad artist, finally making good money. And he was making good money during the Great Depression. Nevertheless, Geisel in the thirties was an unfulfilled academician, frustrated novelist, and semi-employed humorist making ends meet with what he considered blood money. He wanted to be a downtown aesthete, but he was a slave to Madison Avenue, and living uptown to boot on Park in fact. His seemed to be the good life. Since he could do a year's worth of Flit work in a half-a-year, he and Helen were able to spend four months annually in Europe. For a fellow who had a lifelong wanderlust as Geisel did, this was the life of Riley. Or was it? "I'll tell you," Geisel said, "I was really tired of doing gags and cartoons that would disappear next week"

The stroke that led to yet another sea change in Geisel's career was struck when he was sailing homeward across the Atlantic aboard the M.S. Kungsholm. It was a storm-tossed crossing and "all we could do was sit and listen to the damned engine," Geisel recalled. He led his fellow passengers in a little game: Make up a rhyme that could ride the da-da-da-dum rhythm of the ship's churning engines. One of Geisel's limericks ended with "And that is a story no one can beat,/ When I say that I saw it on Mulberry Street."

"When we got back to New York," said Geisel "that damned couplet kept going 'round in my head. couldn't get it out. First thing I knew, was writing a children's book about it."

Mulberry Street is a byway in Springfield on which Geisel's grandfather owned property, but this association did not present itself to Geisel as he painstakingly made his way through draft after draft of what was to become And to Think that ISaw It on Mulberry Street. Finally, Geisel felt he had it right. Twenty-eight (or 27 or 29, depending upon accounts) publishing houses disagreed. One day Geisel was heading up Madison Avenue with the manuscript under his arm and rejection in his heart. He was either (again depending upon which account you believe): A. Heading for the subway to scatter the pages upon the tracks, or B. Heading home to burn them upon the grate.

Whatever.... He was walking up Madison Avenue. He bumped into Mike McClintock '26, an old college pal. McClintock asked Geisel what was up, and Geisel said nothing was up, adding that he'd been trying to peddle a kid's book but without any success. McClintock replied, "I've just been named juvenile editor of Vanguard Press and you're standing right in front of my office. Come on upstairs." Twenty minutes later, the deal was done.

The Godivas project had been urged upon Geisel by his friend, Bennett Cerf, who was the major domo at Random House, which published the book. The softcore Seuss volume, which the Flit people allowed for reasons best understood by the Flit people, sold around 500 copies out of a printing of 10,000. "I can't draw convincing naked women," was Geisel's only explanation for the debacle. "I guess I didn't make them sexy enough. I put their knees in the wrong places."

Despite the bomberoo book for grown-ups, Cerf wooed Geisel energetically and won him away from Vanguard. By 1940 Geisel had four kids books and the failed adult offering to his credit, and was clearly finding a direction. What he called "the brat-book business" was seeming, more and more, to be his calling.

But first something else — duty — was to call.

Even before Pearl Harbor Geisel campaigned against America's isolationist stance via three editorial cartoons in the newspaper PM. "The onlyangry pictures I ever did in my life,' he said years later. "And I'm not proud of their overstatement but I still believe in what I was saying." Most of what he was saying.. He did not mean to say what he apparently had said about dachshunds in the cartoon where he drew them in the form of Nazis. The dachshund lovers of America raised an awful ruckus. "I learned it was better to draw imaginary animals," said Geisel.

Immediately after the bombing in Hawaii, he joined the army as a captain; he would eventually make lieutenant colonel. He was mustered into the information-and-education division, and found himself working in an old Fox film lot under the famous director Frank Capra, who died but two weeks before Geisel himself did in September. Geisel always described the army films he worked on as"propaganda," but clearly there was more to his indoctrination movie, "Your Job in Germany," than that. It must have been pretty good, for when it was reissued as "Hitler Lives!" it won an Academy Award as best short documentary of 1946. In 1947, a Geisel documentary on Japan's role in the recently ended war, "Design for Death," won him his second Oscar. At about that same time, he was commuting to the Warner Brothers lot daily to work as a writer on a screenplay that would become, much amended and a decade later, James Dean's "Rebel Without A Cause."

But the studio scene simply didn't suit the shy ex-colonel; he wasn't comfortable with the confusing, collaborative process of movie-making. "I quit because I realized my metier was drawing fish," he said simply Others maintain that once Ted and Helen had bought "The Tower" in '47, Geisel's desire to work alone, quietly and intelligently, became irresistible.

It's too simplistic to say the Geisels retreated to the mountaintopo. They did not. Helen became, over the years, a driving force in the La Jolla Library and Ted served on the town council. The Geisels were regulars on the local social scene. "He would go to cocktail parties, and he would talk to you if you were there," says a friend. "He would stand quietly in a corner, in his bow tie, and not make a big deal about approaching you. But if you approached him, he was a friendly and interesting conversationalist. Funny, intelligent, a bit shy."

So he did not become Seuss the Recluse, the Howard Hughes of Kid Lit. In fact and for instance, under his own terms he took a couple more stabs at the movies. Each of these added an interesting item to an increasingly fascinating resume.

In 1951 he made the animated film "Gerald Mcßoing-Boing." This was conceived as a phonograph record about a little boy who only spoke in sound-effects. Said Geisel: "As soon as I heard the record I knew I was in the wrong medium." His instincts were right. The cartoon won him his third Academy Award, and if there was ever a multi-Oscar winner with a more diverse honor roll than "Hitler Lives!" and "Gerald McBoing Boing," then Heaven only knows who it is.

In 1952 he wrote and designed "The 5,000 Fingers of Dr. T." This live-action film was as bizarre as any Oobleck, Wocket, or Screaming Abominable. Hans Conried later of "Lost in Space," played a mad music teacher who had imprisoned 500 boys. They had been instructed to practice simultaneously on a winding, mile-long piano, while "Wizard of Oz"-style guards stood ominously by. The movie, which was just released on video earlier this year, has become a cult classic. Heavy-metal Wayne's Worlders who haven't read Seuss since Horton heard the Who now feel "The 5,000 Fingers" was Ted's most excellent adventure.

Yes, clearly then: Geisel regularly descended to the valley from what he began calling, alternately, "The Tower" or "The Castle." But just as clearly, the serenity atop the mountain came to be central to his life and work. He and Helen started almost immediately to renovate and add to the watchtower, and to accumulate plants and pets. The Geisel household had as many as 25 different cats over the years. In one era, there was but a single Irish setter. Then there came a segue back to cats, with a pair named Thing One and Thing Two. The animal population of Mount Soledad was always in flux, much like that of Geisel's literary zoo.

Geisel's primary source of recreation became gardening. His central method was to move rocks around. "That's what I do. I have a rock garden. And then I get tired of looking at the rocks in one arrangement, and so I move them."

The gardening was a break from the intense, rigorous creativity that ensued in the study. Now that Geisel was entrenched in the book-making business, he had two different books in progress at all times. He would start each by sketching on a large artist's pad, and he would hope that the doodles would evolve into animals and that the animals would begin to interact. On the cork bulletin boards above his desk he would pin his sketches and watch storylines develop. He was always writing for himself, not for kids. "Too many people write down to kids," he said. "I feel I'm just a grown-up kid, and if I'm interested in the book, they will be."

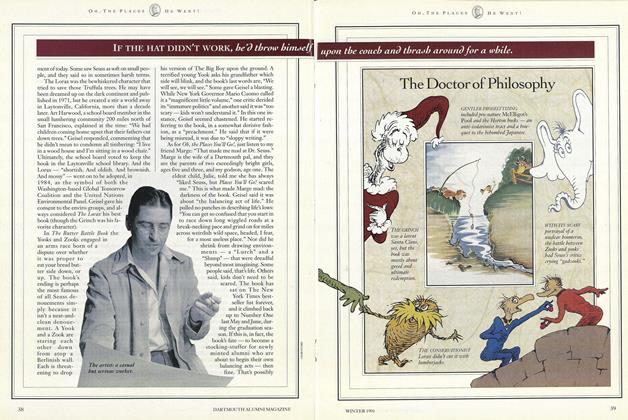

If one book stalled, he would switch to the other. If both books were stuck, he would repair to his closet and retrieve "a thinking cap." It might be his Ecuadoran fireman's helmet, or his rock-wallaby fur, or one of a hundred others. If the hat didn't work, he'd throw himself upon the couch and thrash around for a while.

He trusted, as many a creative artist has, in inspiration. Take Horton the elephant. "I was just doodling on some transparent paper," said Geisel. "I had drawn a tree, and I had drawn an elephant. When one paper slipped from the board and lighted on the other, it looked as if the elephant were sitting in the tree. I stopped, dumbfounded." He mulled the situation for a month. "Finally I said to myself, 'Of course! He's hatching an egg!"

Although this story has the slightly otherwordly tinge that colors some of the better Geisel anecdotes, there is ancillary testimony that Geisel did indeed struggle with the perplexities facing Horton. Larry Leavitt '25, who knew Geisel at Dartmouth, tells the tale: "I remember years ago my wife came back after her women's reunion lunch and told me that Mrs. Geisel was all hot and bothered because there was a book overdue at the publisher's and Ted had an elephant up in a tree and couldn't figure out what to do with him."

While Geisel sometimes relied upon inspiration or chance, he always assured himself a modicum of forward progress through good old puritan work habits. His practice was always to stay at his desk eight hours a day, whether art was being created or not. Eventually, something happened. Sometimes the something took longer than at other times. As we have seen, Geisel internalized Horton for weeks before he figured out the egg gambit. It took him a year to do the seemingly simple Fox inSocks. Among the various traditions surrounding the conception of Seuss books, only the one about The Lorax implies any ease at all.

As that story goes, Ted was in a down-mode in La Jolla. He and Audrey, his second wife, decided to go on another of their vacations, this time to Africa. Geisel was sitting poolside, thinking how odd it was that these leafy-topped African trees looked so much like the ones he had been drawing since his youth. Next thing he knew, the trees were being felled. "Audrey!" he exclaimed. "They're cutting down my trees!" Feeling upset, he grabbed a hotel laundry slip and scribbled a rough draft of The Lorax on the back of it. "Truffula Trees are what everyone needs," he wrote. "Plant a Truffula. /Treat it with care. /Give it clean water. /And feed it fresh air. Grow a forest, /Protect it from axes that hack. /Then the Lorax and all of his friends may come back." That was one amazing laundry slip.

Except for that "ecological allegory,' produced in a burst of anger, Geisel seemed to have Hortonesque difficulties in delivering his other works. "My books look as if they've been put together in 23 seconds," he often said, "but 99 percent of what I do ends up in the scrap basket."

Really? Ninety-nine percent? "I believe it," says Sydney Lea, a novelist and poet of high repute. Lea, a former professor of English at Dartmouth and past editor of the highly regarded Bread Loaf Quarterly, lives in Orford, New Hampshire, where he regularly reads Seuss to his three-year-old daughter. "He clearly worked as hard as any poet. His stuff wasn't accidental. I've read 'most all of the Seuss canon, and I never caught him out, not technically."

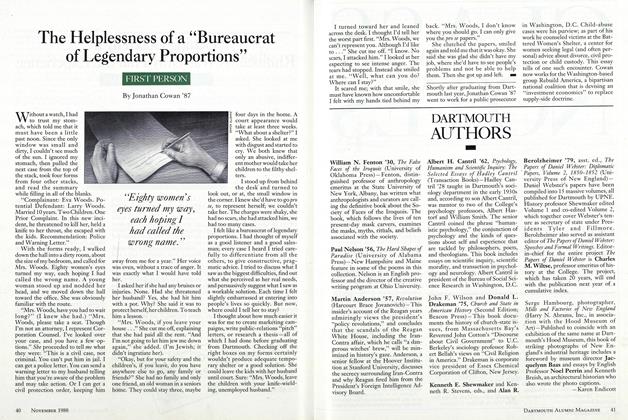

The combination of brilliance and hard work were bound to pay off hugely for Geisel, or so it seems in retrospect. They did, in 1957.

Geisel was, in 1956, a successful writer of children's books. Subsequendy, he was a phenomenon: a valued educator, a renowned poet, a bestselling author of extraordinary size, eventually an American icon.

This large jump in stature was spurred by a 1954 article in Life magazine by the novelist John Hersey Hersey, in an essay entitled "Why Do Students Bog Down on the First R?", complained that America risked raising a generation of dullards because its children's literature was so abysmal. Hersey argued that the stuff kids were told to read Dick and Jane and Spot and that lot was so boring kids wouldn't read it. "Pallid primers," he called them, populated by "abnormally courteous, unnaturally clean boys and girls." Hersey went further, pointing out that the fiction kids might want to read, like those terrific stories by Dr. Seuss with their "jaunty juveniles," they couldn't read. The language was too advanced, and the books had to be read to the little ones, rather than by them. Why (Hersey asked) doesn't a fellow

Geisel, noble Dartmouth C&G knight that he was, picked up the gauntlet. He told Cerf he wanted to do a primer. Then he asked Cerf: What's a primer, anyway?

A primer, he was told, was a book with a set number of words in it, the outside limit being the vocabulary that a child of a particular age might master. Geisel was told that a kid of, say, five could swallow, say, 225 words. Okay, said Geisel. He took a list of 225 simple words and looked at it for a long, long time. Nothing came to him. Then he picked the first two words on the list that rhymed "Cat," as it happened, and "Hat" and he went from there.

"I went with the verse because in verse you can repeat," he said. "It becomes part of the pattern. To teach, you have to repeat and repeat and repeat."

The birth of The Cat in the Hat made Horton Hatches the Egg look like painless labor. Geisel had until then written only what he termed "novels" tales for intelligent parents to read by the fire to their kids. But now he only had 225 words to push forward this wonderful story about a brassy feline trashing the house while moms away. (Its fun to note that Seuss's seminal work incorporated this single most appealing plotline in kiddom, as the quarter-billion-dollar movie "Home Alone" has reconfirmed.) Every time the cat was about to do something outrageous, Geisel ran short of words. "It took me a year of my getting mad as blazes and throwing the thing across the room," he said.

Finally, it was finished albeit at 228 words. Random House simply couldn't keep those 22 8 in print. The Cat was a national sensation. Whereas previous Seuss titles like On Beyond Zebra and Scrambled Eggs Super could be called upon for respectable five-figure sales, The Cat didn't even pause at 100,000. (Very quickly there were French editions, Swedish, Chinese, and braille editions. It was a publishing wonder along the lines of, well, along the lines of 1990's Oh, the Places You'll Go!, which still hasn't been dislodged from the Times bestseller list 20 months after hitting the shelves. All across the country kids were demanding The Cat. Parents were happily buying it for them. Five-year-olds were hooking plastic fish and winning gifts from baskets numbered 8, and all witches worth their broomsticks were giving out copies of The Cat in the Hat to their clients.

Later in 1957 Geisel published How the GrinchStole Christmas, a novel, which did very well. In the latter part of the year he was putting the finishing touches on both yertle the Turtle and The Catin the Hat Comes Back, the former destined to become another classic novel and the latter to be a... a what?

A Beginner Book. Beginner Books were and are, according to Random House's prosaic definition, volumes whose "rollicking verse and wacky pictures entice young children to undertake the arduous task of learning to read." They were, in other words, scientific. Whereas the novels were moral tales unbounded by the constraints of any word-list, each Beginner Book would be written to specifications. One would be for a five-year-old, one for a four, the next for a three. But all of them would be lively, interesting, vital, and fun.

And how to insure this? Easy. Make Geisel the editor-in-chief of this new Random House offshoot.

Established in The Cat's wake, B.B. was a fourperson cottage industry wholly owned by the Cerfs and the Geisels. Helen served as publisher and as a contributing author, not to mention as her husband's best editor. The Cerfs constituted half the editorial board. Geisel and his three associates thought deeply about each new manuscript presented them: Would kids read it over and over? Can we skew downward even farther and create a book for a three-year-old? Bennett Cerf was always saying, "Yes! Yes!" knowing that if he challenged Geisel there would be results. His faith in the man, which he had steadfastly retained even as the returned boxes of Lady Godivas piled up in Random's warehouse, was being rewarded.

These were the headiest days for Geisel. TheCat was fast becoming a beast that would eventually earn more than $10 million in books, toys, and television. Geisel was producing instantly bestselling novels that would, over the next four decades, come to total 26 in number (HappyBirthday to You in 1959 and 1984's The Butter BattleBook among them). He was fashioning increasingly ambitious Beginner Books that would eventually number 14 (One Fish Two Fish Red Fish Blue Fish in 1960 and 1963's Hop on Pop among these). Several of the Beginner Books are flat-out masterpieces; Green Eggs and Ham (1960), is perfection despite the fact that it was concocted to win a $50 bet with Bennett Cerf that Geisel could write a book with fewer than 50 words. "I call those books Eggs and Ham, Fox in Socks, RedFish Blue Fish the 'mantra books,'" says a Dartmouth friend of mine who has two kids. "The language gets imprinted in your head forever. Our son, George, is only three, and he's already heard Green Eggs and Ham at least 50 times. Try to find an author, no matter how great, with that kind of influence."

If there was a downside to GE&H, it was that after its publication Geisel had to suffer through many an elegant banquet in his honor that featured green eggs on the side. "The worst time," he once recalled, "was on a yacht in six-foot seas."

Geisel started producing ultra-beginner books, called Bright and Early Books, for true toddlers (Marvin K. Mooney Will You Please Go Now! in 1972 and 1974's There's a Wocket in My Pocket, for instance). He was, meanwhile, issuing unsigned and sorta-signed miscellania: poems that didn't lend themselves to Seussian art and therefore were bylined "Theo LeSieg," scripts and design for the TV specials that were made from his '57 classics The Grinch and The Cat, posters for enviro groups and anti-drug campaigns.

And, of course, he was winning awards by the cat's hatful. The "Grinch" and "Horton" television programs each took home a Peabody. The "Lorax" film won several awards, and "Halloween is Grinch Night" won an Emmy as Best Children's Special. So did "The Grinch Grinches the Cat in the Hat," which is the Frankenstein-meets-the-Wolfman of kids' half-hour tube shows. He won both a special Pulitzer and a New York Public Library Literary Lion award. He received a Dartmouth honorary, a Princeton honorary, and a bunch of other honoraries. "Dartmouth was the first to make my 'doctor' legitimate," said Geisel of the 1955 bestowal.

The awards were nice, but what they signified was nicer. Importantly to the man himself, he was finally being taken seriously as a writer and an artist. This is something he had always quietly coveted. Cerf said that of all Random House authors of the middle century, Faulkner and O'Neill included, Geisel was the only genius. Geisel smiled when Cerf said that; he did not say, "Oh, Bennett, don't be silly." Hersey, meanwhile, said that the book provoked by his Life essay was precisely what he had in mind. It was, he said, a harum-scarum masterpiece."

Geisel, at last, was being called an educator. That had always been his goal.

THE SEUSS MOMENTUM NEVER lagged. Even as he hid behind his Seussonym all the while, and even as he ventured out from La Jolla for publicity purposes more and more infrequently, Geisel acquired a transcendent fame a larger-than-life, multi-media, only-in-America fame. "You know how magical his name became?" asks Leavitt. "I'd be reading my grandchildren a Seuss book and when I'd finish I'd say, 'I know the fellow who wrote that.' Well, their eyes would get so wide. It was like saying I knew Mickey Mantle."

"You know what's weird?" asks Ann Geisel, a librarian in Peterborough, New Hampshire, whose husband's grandfather was Theo Sr.'s brother (got that?). "You know what's weird? A teacher at the local grammar school has a Seuss Day every year and she marches her class right in here so they can look at a real relative of his."

The fame thing, as Mr. Bush might put it, changed Geisel not a bit. "It's all really pretty inconsequential, isn't it?" he said. Thats a comment that those who knew him well would expect. "It was just like him," says a friend. His associates all maintain that Geisel, while probably a genius, was a regular guy, a shy guy with a wry sense of humor. This dry wit didn't always translate precisely in his interviews. It led some journalists to think Geisel a Wiseguy, others to think him reticent, and still others to think him contrary or even curmudgeonly. This, in turn, led some readers to misjudge Geisel. It even, over the years, made for some widely held misconceptions about Dr. Seuss, paramount among them that he didn't like kids. "You have 'em, I'll amuse 'em," Geisel always said in stock response to the oft-asked question as to why he never fathered any. Or he would tell the story about the book-signing: "The kid's hand was down his throat up to his elbow. The woman pointed to me, looked at the boy, and said, 'Now take your hand out of your mouth and shake hands with Dr. Seuss.' And he did!"

Some grownups read those things and thought Geisel didn't like kids.

Geisel liked kids fine. He did not romanticize kiddom, as many adults are wont to do, and perhaps this led to the conclusion that he was insufficiently loving. But perhaps, just perhaps, his attitude was why he com- municated so well with the kids themtude "I don't patronize," he said. Or, with some seriousness: "They're like grown-ups. There are good ones and bad ones. I talk to all of them, but I let them know there are good ones and bad ones."

We'll return to kids in a minute when we look at some of Geisel's books; but first, let's finish our chronology:

Geisel always joked that he never became a father because he couldn't have tolerated having the children running into his study, telling him what to write, and screwing everything up. That's probably not the real reason, but whatever the reason was, it remains unrevealed. Helen never publicly commented upon it during their 40-year, largely happy marriage that ended with her death in 1967.

Geisel married Audrey Stone Dimond in 1968, and at age 64 he inherited two teenage daughters from Audrey's first marriage. Audrey would not necessarily be the literary teammate that Helen had been, but she would be every bit the friend and partner.

Audrey had once been a nurse, and, rather too sadly, this proved to be a comfort in the past decade and a half. Geisel was beset by infirmities. "The ailments bothered him," says a friend. "There's no question they bothered and bugged him."

But they never broke him. In the seventies and eighties Geisel slipped only slightly from his book-a-year pace, and he continued to deliver the occasional speech, speechaccept the occasional award, sail out upon the occasional uncharted waters. In 1983 he signed a deal with Coleco to design and market toys and even video games based on 300 Seuss animals. Said a Coleco VP: "Market research has demonstrated a tremendous amount of awareness and preference for the Dr. Seuss characters among children and their parents." As if they needed market research to determine that.

In 1984 he received the special Pulitzer.

In 1985, Geisel, rather extraordinarily, appeared with the Rockettes on the stage of Radio City Music Hall. He was one of the stars at the Night of One Hundred Stars fundraiser.

Later that year he brought out You're Only OldOnce, his words-and-pictures book "for obsolete children" about the travails of old age. "That book wrecked my social life," he said. "Prior to that, the only places that I was ever invited to go were kindergartens to have cocoa. Suddenly I was getting invited every day to have martinis in old folks' homes."

Geisel was too infirm to travel along with a major 1987 retrospective of his life and work, Dr. Seuss from Then to Now. But he did talk to museum curators nationwide who were staging the show, and he helped with the book that accompanied it.

Then came Oh, the Places You'll Go!

Then came a compilation, Six by Seuss, published last fall.

Then came the movie musical.

And then came his death.

All of it, save the last item, seems, when the maladies that were leading toward the end are taken into account, not only remarkable but rather courageous. When an artist paints through cataract problems, or a writer forces himself back to the desk even though he's "pooped and workedon by doctors," then that artist and that writer are doing yeoman duty. When they laugh in the face of illness (You're Only Old Once), then they're doing brave work. When the artist and the writer are halves of the same person, and at 87 they take on the challenge of creating a full-blown Hollywood extravaganza for Tri Star Studios well, then they're crazy. From a financial standpoint, no one needed to work less than Geisel did near the terminus of his life. But apparently, no one needed to work more.

Perhaps the most amazing part of it was, the work didn't suffer and Geisel never went out of style; this doctor was always in. His books are still on school reading lists and bestseller lists. The Catin the Hat was a running gag on the "Murphy Brown" TV show the week of Geisel's death. Earlier this year, Entertainment Weekly divulged: "The Cat in the Hat is back as a fashion upstart." In this case, the magazine was reporting on the "kooky, squashed tramp lid [that] seems as übiquitous as tattoos among the MTV set." In another issue, the same magazine reported on the Pediatric AIDS Foundation's effort to assemble a benefit disc of children's songs. But, according to Entertainment Weekly, when the rap group Digital Underground was set to record Green Eggsand Ham to a hip-hop beat, Geisel nixed the track. "It's Ted's policy not to allow any third parties to adapt his work except under his direct supervision," agent Bob Tabian told the magazine. The "pure volume" of requests for his work made it impossible to grant exceptions.

That may sound grinchy when you're talking about kids with AIDS, but such a policy certainly contributed to the longevity and consistent excellence of Seussian media. Geisel knew what he was up to, and he knew that it would be easy for others to misinterpret what he was up to. What was he up to? What had he always been up to?

Primarily, reading. Geisel asked of children that they read. And furthermore, he asked them to develop life goals and a set of morals, if not a political persuasion. His books lasted, and will last, because, at least since the forties, they've not only been entertaining but topical. They have had relevance for children. They have seemed, to kids, important. Geisel demanded, in a subtle but not sneaky fashion, that children think about pollution, fascism, racism, culturalism, meanness, and other things that have unequivocal good and bad sides to them. "Kids can see a moral coming a mile off and they gag at it," he said. "But there's an inherent moral in any story."

HIS SEARCH FOR SOMETHING more than mere narrative started, I think, with Horton Hatches the Egg in 1940. Horton maintained that "an elephant's faithful one hundred percent," and that's as strong a call for resisting Germany as the cartoons in PM had been. Geisel's quest continued with McElligot's Pool, published in 1947. It's a wonderful book, a book about the power of dreams. ("Oh, the sea is so fall of a number of fish, /If a fellow is patient, he might get his wish!") M's Pool won a Caldecott Award, the brat-book Oscar. If you look closely, on page three you can find a most-mild anti-pollution sermon: "You might catch a book /Or you might catch a can. /You might catch a bottle, /But listen, young man ... /If you sat fifty years /With your worms and your wishes, /You'd grow a long beard /Long before you'd catch fishes!"

Dr. Seuss became, increasingly, a philosopher. Yertle (1950) showed a Hitler lurking beneath the despotic turtle's shell. This, too, was safe enough terrain, since Hitler had been an inarguably bad guy, and also because Yertle got his well-deserved comeuppance: "For Yertle, the King of all Sala-ma-Sond, /Fell off his high throne and fell Plunk! in the pond!"

The Grinch was about greed and self-centeredness.

The Sneetches said that bigotry was bad business.

Sometimes, the lessons being taught caused controversy. Geisel caught flak with the publication of Horton Hears a Who (1954), The Lorax (1971), The Butter Battle Book (1984), and even last year's seemingly innocuous Places You'll Go!

Horton the elephant, faithful one hundred percent, as noted, is one of the sweetest characters in Seuss's zoo. In his post-egg adventure, which marked one of the few instances in American literature that a sequel was the equal of the original, Horton learned that "a person's a person, no matter how small." He learned this about Whos in paiticular. But some people had the foreknowledge that Geisel had learned it about the Japanese during one of his many trips 'round the world. The doctor, to some, seemed engaged in a bend-over-backwards effort to understand people who had waged war scarcely a decade before. Anti-Japanese feeling was still pervasive in the land, and it was far more deep-seated than the Honda-glut resentment of today. Some saw Seuss as soft on small people, and they said so in sometimes harsh terms.

The Lorax was the bewhiskered character that tried to save those Truffula trees. He may have been dreamed up on the dark continent and published in 1971, but he created a stir a world away in Laytonville, California, more than a decade later. Art Harwood a school board member in the small lumbering community 200 miles north of San Francisco, explained at the time: "We had children coming home upset that their fathers cut down trees." Geisel responded, commenting that he didn't mean to condemn all timbering: "I live in a wood house and I'm sitting in a wood chair." Ultimately, the school board voted to keep the book in the Laytonville school library. And the Lorax "shortish. And oldish. And brownish. And mossy" went on to be adopted, in 1984, as the symbol of both the Washington-based Global Tomorrow Coalition and the United Nations Environmental Panel. Geisel gave his consent to the enviro groups, and always considered The Lorax his best book (though the Grinch was his favorite character).

In The Butter Battle Book the Yooks and Zooks engaged in an arms race born of a dispute over whether it was proper to eat your bread butter side down, or up. The book's ending is perhaps the most famous of all Seuss denouements simply because it isn't a neat-and-clean denouement. A Yook and a Zook are staring each other down from atop a Berlinish wall. Each is threatening to drop his version of The Big Boy upon the ground. A terrified young Yook asks his grandfather which side will blink, and the book's last words are, "We will see, we will see." Some gave Geisel a blasting. While New York Governor Mario Cuomo called it a "magnificent little volume," one critic derided its "immature politics" and another said it was "too scary kids won't understand it." In this one instance, Geisel seemed chastened. He started referring to the book, in a somewhat derisive fashion, as a "preachment." He said that if it were being misread, it was due to "sloppy writing."

As for Oh, the Places You'll Go!, just listen to my friend Marge: "That made me mad at Dr. Seuss." Marge is the wife of a Dartmouth pal, and they are the parents of two exceedingly bright girls, ages five and three, and my godson, age one. The eldest child, Julie, told me she has always "liked Seuss, but Places You'll Go! scared me." This is what made Marge mad: the darkness of the book. Geisel said it was about "the balancing act of life." He pulled no punches in describing life's lows: "You can get so confused that you start in to race down long wiggled roads at a break-necking pace and grind on for miles across Weirdish wild space, headed, I fear, for a most useless place." Nor did he shrink from drawing environments a "Lurch" and a Slump" that were dreadful beyond most imagining. Some people said, that's life. Others said, kids don't need to be scared. The book has sat on The New York Times bestseller list forever, and it climbed back up to Number One last May and June, during the graduation season. If this is, in fact, the book's fate to become a stocking-stuffer for newly minted alumni who are about to begin their own balancing acts then fine. That's possibly the most suitable role for this volume. Perhaps when Marge's kids are graduating from Dartmouth, they'll receive a copy of the Tri Star musical video, and they'll love it.

Content is one thing, of course, and another is style. There's a final question that needs to be asked about Seuss lit: Is it art? Can the poetry contained within brat books constitute art?

"Oh God yes," says Syd Lea, the bard of Orford to whom I return, this time for aesthetic analysis. "First, he had this crazy conversational quality in his poetry that's unique. Fox in Socks is extraordinary in this way. And Green Eggs andHam, the 'I do not like it, Sam-I-am' bit: it's one of the great absurdist openings of any piece of contemporary literature. The verve with which he invented proper names any poet dealing with narrative concerns would envy him this, and also his way to keep the language lively while the story advances. He was an enviable stylist, an enviable metrist, and a most enviable narrator a real pro. I think, of its kind of poetry, it's matchless.

"Look at The Cat in the Hat the part where the fish in the bowl, the super-ego, is having those problems."

I just happen to have the book handy, and I start to reato read: "But our fish said, 'No! No! /Make that cat go away! /Tell the Cat in the Hat /You do not want to play. /He should not be here. /He should not be about. /He should not be here /When your mother is out!"'

"Keep going," says Lea, enjoying himself.

I take a breath.

"'Put me down!' said the fish. /'This is no fan at all! /Put me down!' said the fish/ I do not wish to fall!"'

Well, anyways, I read on the cat balanced the fishbowl on his umbrella as he stood on the ball with the cup on his hat and a book in his hand and the milk, the cake, the rake, the toy ship, the little toy man, and the red fan all came into play and then, of course, "he fell on his head!"

"Ah, okay," says Lea. "Now what we're dealing with there, and this is serious, it's called dactillic diameter, those passages, and he really knew how to exploit that poetic foot for its full worth. Talk about strange bedfellows: Frost had the same talent. Frost knew how to work the meter and always had the stress fall exactly where he wanted it to fall."

"Alright, alright, alright," I interject. "But does it matter? Is it important to an audience of children that the poems are sublime as well as.. .fun?"

"Absolutely it matters," says Lea. "Kids wouldn't have stuck with him if he were bad. It's impossible to divorce style and content, and the thing that made his poems and stories so memorable was his mastery as a formalist. Now I'm not grinding an axe about free verse here, but it was his great talent as a formalist, his use of meter and rhyme, that made these things work, and made the kids memorize the poems ems, the words, the stories themselves. My three-year-old can quote long, long sectors of his books now, and even when she was two I would read her a Seuss rhyme and leave off the last word and she would fill it in. That's important in a learning sense, and it's also important because he wrote a memorable poem that worked in a wonderful fashion, that a human being wanted to remember."

Geisel, again, demurred; he always demurred. "I am not a poet, really," he said. "And I'm a cartoonist, not an artist. I can't draw. I couldn't draw a good picture of a table and chair. My style is a matter of taking my mistakes and capitalizing on them. When I draw an elephant I try to draw as good-looking an elephant as I can, but I always get too many joints in the leg and that sort of thing."

The thing is: It was a lie, and he knew it. "Ted," says a friend, "was very serious about his work, and always wanted to be taken seriously, and was glad that he was so. He felt the work was good. He wanted others to feel that way too. He didn't long for adulation personally, but he wanted the work to be deemed successful. Helen really was the only one who could criticize the stuff Ted didn't like criticism. He really didn't want to hear it. Maybe Audrey criticized the texts too, I don't know. But the fact is, Ted worked hard to get it right, and when he thought he had it right he wanted the world to concur in that opinion. It's the same with most people, isn't it?" Well, it probably is.

AND SO, THERE WE ARE: A PEEK at a wonderful 87-year life and the works thereof that will live forever. I finish this project reluctantly; it has been, I must say, a kind of respite. Whenever I've been able to steal an hour to do some more Seuss, I have found myself transported to a world of Collapsible Frinks and Big-Hearted Moose and Dr. Derring's Singing Herrings. What better place to be? But now I must leave that world, and I'm sad about that. Furthermore, I realize now that I'll never meet Dr. Seuss and I'm sad about that too. Meeting him, whether I admitted it or not, was my hope in asking the editor of this magazine if I could go forth into the places that Geisel went. Ever since The Cat in the Hat made all the difference for me and my brother, I wanted to meet the person who could create such a wonderful tale, who could inspire two kids to want to read read more, read again, read first thing each morning and read last thing each night. Herein I plotted a way to meet him. And now, of course, that's out of the question.

I have a wish, a wish that could come true only in a story by Seuss, one of those magical, poetical tales. My wish is based upon yet another anecdote, one that Geisel told a hundred times: "Children come to my door and say, 'I want to meet Dr. Seuss.' I say, 'I am Dr. Seuss,' and they simply refuse to believe me. They expect me to be a cow with a nose that lights up, or to be Santa Claus."

So what I wish is, I wish I were five, maybe six. Because if I were still at that scared-by-witches age, I wouldn't have to inquire of editors. If I were five I could proceed apace through the morning mist that shrouds the Pacific shore, and I could start to climb. I could, with others my age, ascend Mount Soledad toward the castellated form that crowns it that strange Xanadu surrounded by trees (are they Truffulas? No, they're eucalyptus). I would keep my eye on the odd pink watchtower that sprouts from the center of the stucco fortress like the cowlick of a Who in Whoville. No one dares impede a five-year-old's progress, and so after a morning of climbing I would reach my goal. I would knock on the door. A thirl man with white hair parted in the middle and an aquiline nose (that does not light up) would answer my knock. I would tell him that I want to meet Dr. Seuss.

"I am Dr. Seuss," he would say.

For you see, I would be five, and he would still be alive.

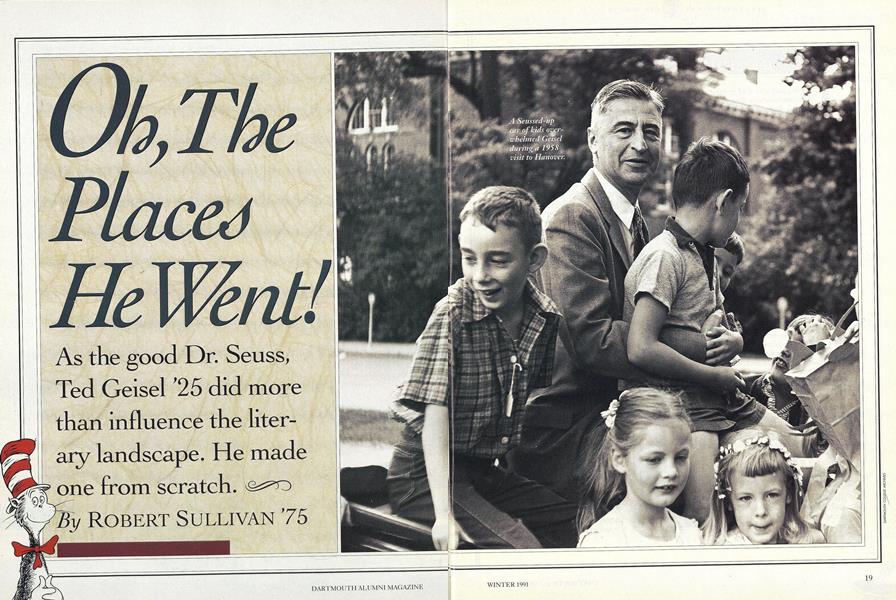

A Seussed-upcar of kids overwhelmed Geiselduring a 1958visit to Hanover.

Despite appearances, Tedwas a well-adjusted kid.

Red Smith '17 sentmany Springfielders Dartmouth-bound.

The doctor hits his beastly stride: In the 1920s and '30s,forjudge and the original Life, Seusses of varied bylines drew classically Seussian fauna of varied shapes.

Geisel's toil for Madison Avenue pr oduced ephemeralan but much-needed moola and a life on Park Avenue.

Bennett Cerf's confidence inTed's ladieswasn't asmisplaced as itfirst seemed.

He saw actionin the Hollywood theater.

FrankCapra

As spouse and fellow brat-book editor; Helen couldcriticize Geisel's art as few were allowed to.

Geisel's vision for the "5,000 Fingers of Doctor T" wasas bizarre as any Oobleck or Screaming Abominable.

In 1955, two years before the Cat was behatted, the great man's alma materbecame the first institution to legitimize the doctor as a Doctor.

The beau-chapeaued felinechanged everything. Everything.

Geisel married Audrey Stone Dimond in 1968 andDr. Seuss finally got kids of his own.

The plastic menagerie that he made for the Coleco toy company bore an unmistakable stamp.

The artist: a casual but serious worker.

For the 1932 Carnival Geisel returned as a snow-sculpture judge.He sculpted a beast of his own an "Alabastard" for Sig Ep.

Artist as artifact: A 1982 portrait by artistEverett Raymond Kinstler now bangs in Baker.

Geisel was a giantamong all, butprimarily a giantamong kids. Maybe viva forever.

HIS DAD HAD WANTED HIM to go to Yale, but young Teddecided to bead up, rather than down, the Connecticut River.

As A CONSEQUENCE OF HIS PUNISHMENT,Geisel was wad relieved of hit editorship at the Jacko.

CERF SAID that of all Random House autbors of the middle century, Geisel was the only genius.

HE WONDERED if there mightn't be a brighter future forhim in forging this yet-indefinite union of literature and art.

GEISEL PROPOSED, Painter accepted the tireblew, and the two of them Landed in a ditch.

THEN HE PICKED THE FIRST TWO WORDS on theist that rhymed "Cat," as it happened, and "Hat."

He STAYED AT HIS DESK eight hours aday whether art was being created or not.

THE WORK DIDN'T SUFFER and Geisel neverwent out of style; thh doctor was always in.

THERE'S A FINAL QUESTION that needsto be asked about Seuss Lit: Is it art?

If THE HAT DIDN'T WORK, he'd throw himselfupon the couch and thrash around for a while.

GEISEL, AT LAST, was being called aneducator. That had always been his goal.

I HAVE A WISH, a wish that could only come true in astory by seuss, one of those magical, poetical tales.

Robert Sullivan is a Sports Illustrated editor and a contributing editor of this magazine.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

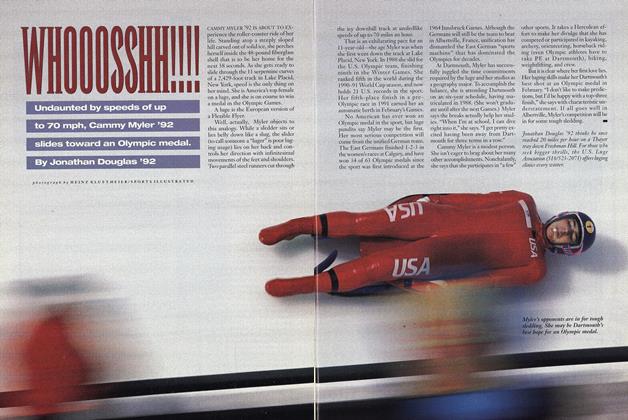

FeatureWHOOOSSHH!!!!

December 1991 By Jonathan Douglas '92 -

Cover Story

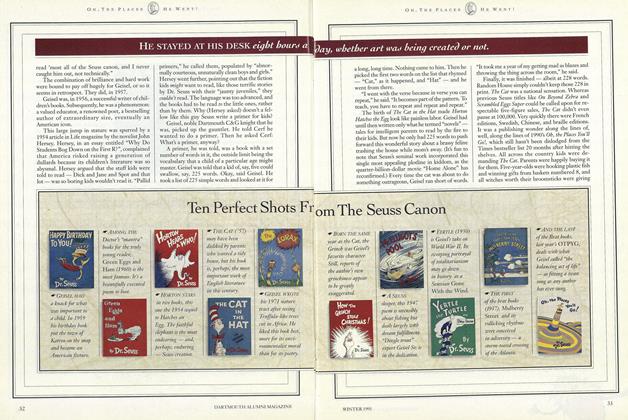

Cover StoryTen Perfect Shots From The Seuss Canon

December 1991 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe Doctor of Philosophy

December 1991 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe Cartoon Warrior

December 1991 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe 'Lanterns' Brightest Light

December 1991 -

Article

ArticleCONFRONTING CHEMOPHOBIA

December 1991 By Professor Gordon W. Gribble, Karen Endicott

Robert Sullivan '75

-

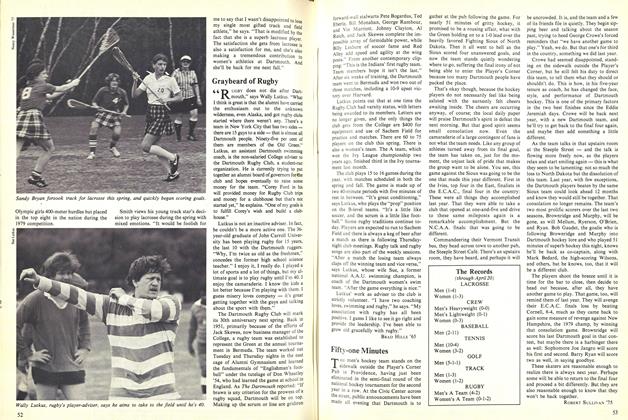

Sports

SportsFifty-one Minutes

May 1980 By Robert Sullivan '75 -

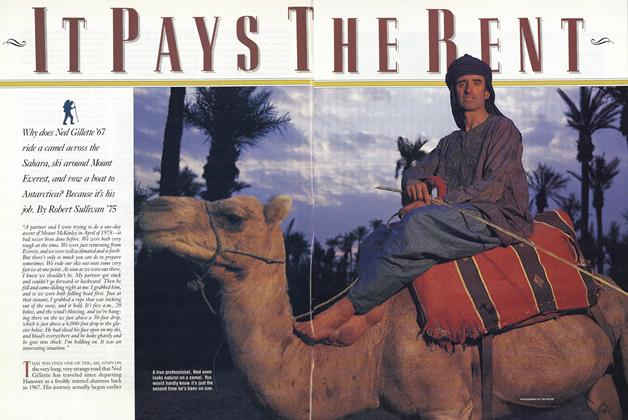

Cover Story

Cover StoryIt Pays The Rent

APRIL 1990 By Robert Sullivan '75 -

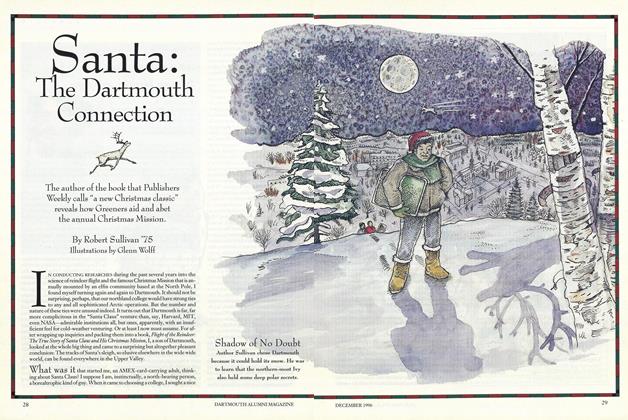

Cover Story

Cover StorySanta: The Dartmouth Connection

DECEMBER 1996 By Robert Sullivan '75 -

Article

ArticleDartmouth Off-Broadway

SEPTEMBER 1997 By ROBERT SULLIVAN '75 -

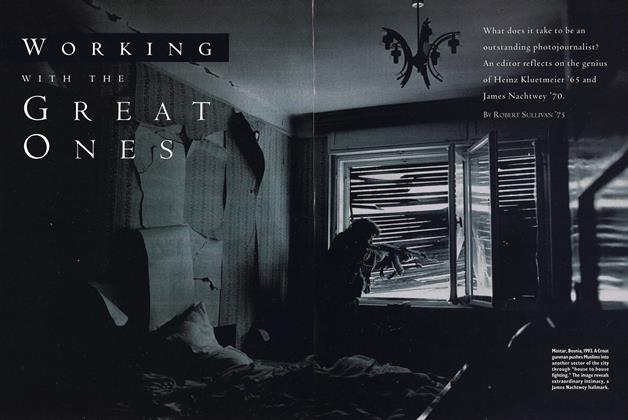

Article

ArticleWorking with the Great Ones

JUNE 1999 By Robert Sullivan '75 -

Cover Story

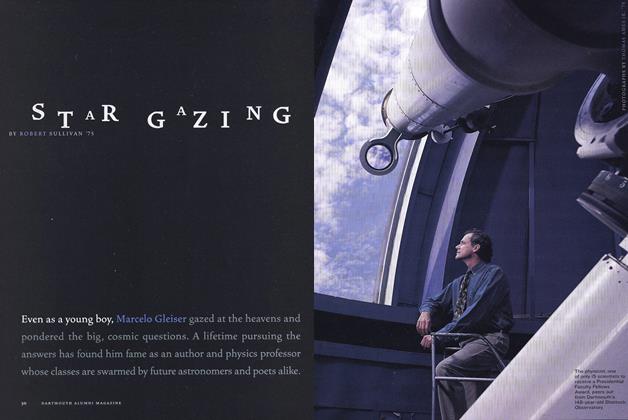

Cover StoryStar Gazing

July/Aug 2003 By ROBERT SULLIVAN '75