We're surrounded by noxious chemicals, but there's no need to panic.

Dioxin, DDT, 2,4-D, PCB, Alar, these are words that strike fear and revulsion in the hearts and minds of most Americans. We live in chemophobic times permeated by illogical and hysterical fears about chemicals. Although most of us once learned enough chemistry to know that all matter is chemical, most of us don't fully realize what this means and find it difficult to distinguish danger from hype. Tragedies like the highly concentrated chemical cloud that killed thousands in Bhopal make people suspicious of even the merest presence of man-made chemicals. Yet the truth is that tracelevel residues of man-made pesticides and herbicides are not a threat to human health and actually pose less risk than myriad naturally occurring chemicals.

In fact, nature teems with chemicals, some fair, some foul. Trees, plants, animals, insects, marine organisms, bacteria, fungi, and volcanoes produce and secrete megatons of chemicals into the environment. For every natural pharmaceutical such as penicillin; morphine; or the new anticancer drug taxol, derived from the Northwest yew there is a natural chemical far more toxic than anything man-made. Such poisons include botulinus toxin, cobra venom, strychnine, and red tide toxins. Aflatoxin, often present in moldy peanuts, is a more potent carcinogen than most man-made carcinogens. Cyanide, one of the fastest-acting poisons known, is found in 180 plant species.

Chemophobia is exacerbated by the difficulty most of us have in understanding magnitudes of chemical concentrations. The press frequently discusses chemicals at the parts-per-trillion level. Unfortunately, the press and the public often confuse and even use interchangeably "ppm," "ppb," and "ppt," (parts-per-million, billion, and trillion, respectively), a failure to realize that these differ by factors of 1,000. Just what is one ppt? It's one teaspoon of fertilizer spread evenly over a garden the size of five million acres. Or one drop of vermouth in 16 million gallons of gin. At this level few if any chemicals are toxic to humans.

Environmental zealots who want to reduce the level of a water or food contaminant to "zero level" or zero molecules do not understand the size of molecular-level concentrations or the difficulty measuring them. A single raindrop, for example, contains 600 quintillion (a billion billion 600,000,000,000,000,000,000) water molecules. Some scientists believe given the inevitable and inexorable phenomena of chemical dilution and dispersal that a single glass of ordinary tap water considered "pure" by today's analytical methods could contain undetectable individual molecules of every volatile chemical ever synthesized by man or by nature.

The epitome of misunderstood chemicals are the organohalogen compounds chlorinated, brominated iodinated, and fluorniated compounds such as DDT, 2,4-D, Agent Orange, dioxin PCB, and EDB. In the wake of highly publicized cancer scares implicating these chemicals, some environmentalists and even some scientists have claimed that halogenated chemicals are not found in nature. Nature, they reason, would not create such "highly toxic and environmentally harmful chemicals."

The evidence is overwhelming, however, that natural enzymatic, thermal, and other processes always present in the oceans, in the atmosphere, and in soil lead to the formation of chlorinated and brominated phenols, dioxins, and a myriad of other halogenated chemicals that previously were thought only to result from the actions of man. In fact, naturally occurring halogenated compounds far exceed in numbers and chemical complexity their man-made counterparts. Plants, marine organisms, insects, soil bacteria, lichen, fungi, forest fires, volcanic activity, and other natural processes produce and discharge hundreds, if not thousands, of halogenated chemicals, including dioxin and chloromethane. The global emission rate of chloromethane from these marine and terrestrial sources is five million tons a year, which dwarfs levels of manmade chloromethane emissions.

Halogenated compounds crop up everywhere. "Limu koku," the favorite edible seaweed of most Hawaiians, contains nearly 100 halogenated chemicals. The ancient Egyptian dye tyrian purple is a bromine-containing chemical produced by mollusks. The sex pheromone of the Lone Star tick is 2,6-dichlorophenol, a chemical very closely related to 2,4-dichlorophenol, which is used to manufacture the herbicide 2,4-D. A newly discovered microorganism produces rebeccamycin, a chlorinated compound with powerful antitumor properties. The list goes on.

But what about our chronic exposure to trace levels of halogenated chemicals like DDT and dioxin? In fact, the toxicity to humans of all halogenated chemical compounds is vastly overrated. Although it is certainly tragic that bird populations have been seriously affected by DDT and other chlorinated pesticides, in normal use and concentrations DDT has never killed a human. The World Health Organization estimates that DDT actually saved die lives of five million people from 1944 to 1953 by killing the insects that carry malaria, yellow fever, typhus, encephalitis, river blindness, and bubonic plague. It prevented a potentially catastrophic typhus epidemic in Naples in 1944. In a surprising twist, DDT has an anti-cancer effect like Vitamins A, C, and E in animals exposed to carcinogens, while the closely related pesticide DDD is the anticancer drug "mitotane," used in treating inoperable adrenal cancer.

Even dioxin seems to be far less toxic to humans than was believed only a few years ago. The EPA official who ordered the evacuation of Times Beach, Missouri, recently admitted that the evacuation was unnecessary. The worst dioxin accident in history, in Seveso, Italy, in 1976, has not resulted in serious harm to the health of the exposed population. The cancer rates of Love Canal residents and of Vietnam veterans who handled Agent Orange are essentially the same as of unexposed people.

We as a species are well-equipped to survive in an environment teeming with "background" carcinogens. A highly devaloped and multivariable natural defence system protects us, within limits, from cancer. Cells that are exposed to the outside world skin, mouth, digestive system are constantly shed and replaced, DNA damaged by radiation or chemicals is repaired by special enzymes, and chemical carcinogens are deactivated by roving "police molecules" such as glutathione. Vitamins A and C, and perhaps others, may play an important role in this immune-defense system. Some scientists even believe that small continual exposure to cancer-causing chemicals is a prerequisite for the very existence and operation of our immune defenses.

As analytical techniques improve, scientists no doubt will detect carcinogens, mutagens, and teratogens (birthdefect causing agents) at the parts-per-quintillion, sextillion, and -septillion levels in everything we touch, eat, drink, or breathe. But we must not waste our energy and resources agonizing about the insignificant risks resulting from such exposures. We should concentrate instead on our most pressing environmental problem: the exploding human population, with its associated pollution, crowding, hunger, disease, and despair.

Hearing Gordon Gribble tell us to relax about chemicals is a bit like watching the scene in "Sleeper" where Woody Allen laughs at the absurdity of the days when people thought that steak and cream were actually unhealthy. Ya wanna believe it, but Allen's a comic; he's supposed to be zany. Gribble's a chemistry professor, he's supposed to like chemicals.

"I hope I didn't give you the impression that I am 'anti-environment,'" Gribble e-mailed the magazine following a phone interview from the University of Hawaii, where he is spending the year as a visiting prof. "Quite the contrary, I love the outdoors and some of my favorite pasttimes are hiking, mountaineering, and camping. I abhor pollution (air and water) as it pertains especially to fouling and staining the great outdoors. I believe that most of it can be traced to overpopulation rather than to a fundamental change in technology, that is, we have had a tremendous increase in technology more automobiles, more power plants, more wood- and oilburning because of the increase in population."

In a personal example of how science evolves, Gribble says that 15 years ago he was wary of dioxin and lectured to Vietnam vets about its potential human toxicity. "Now we've had a chance to study dioxin, and we find that it's not as toxic to humans as we had feared," he says. In a similar weighing of scientific evidence, he offers a corrective to another popular notion: "Pollution may look and smell bad, but except at high concentrations, it doesn't make people sick."

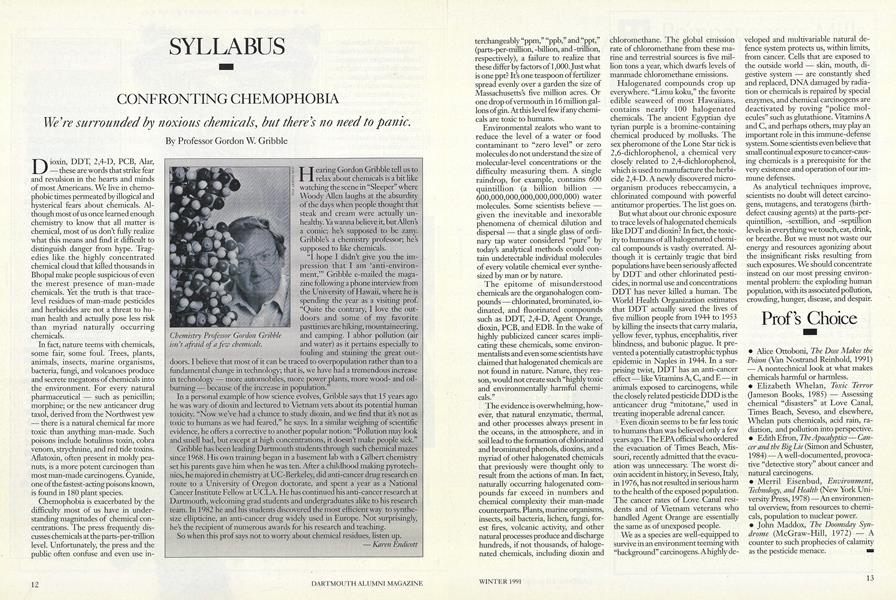

Gribble has been leading Dartmouth students through such chemical mazes since 1968. His own training began in a basement lab with a Gilbert chemistry set his parents gave him when he was ten. After a childhood making pyrotechnics, he majored in chemistry at UC-Berkeley, did anti-cancer drug research en route to a University of Oregon doctorate, and spent a year as a National Cancer Institute Fellow at UCLA. He has continued his anti-cancer research at Dartmouth, welcoming grad students and undergraduates alike to his research team. In 1982 he and his students discovered the most efficient way to synthesize ellipticine, an anti-cancer drug widely used in Europe. Not surprisingly, he's the recipient of numerous awards for his research and teaching. So when this prof says not to worry about chemical residues, listen up.

Chemistry Professor Gordon Gribbleisn't afraid of a few chemicals.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

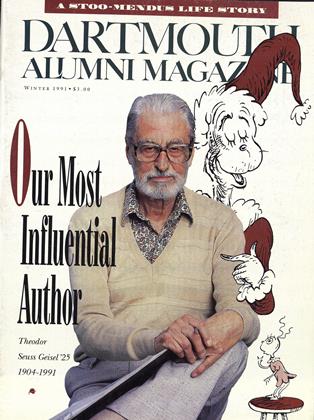

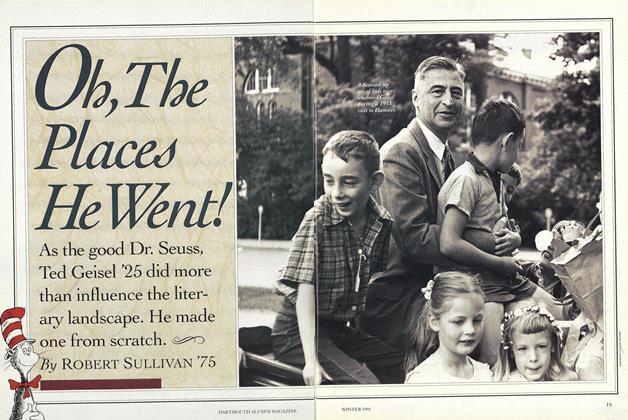

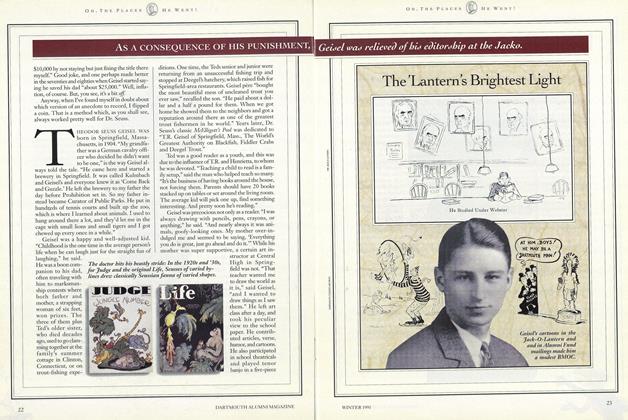

Cover StoryOh, The Places He Went!

December 1991 By Robert Sullivan '75 -

Feature

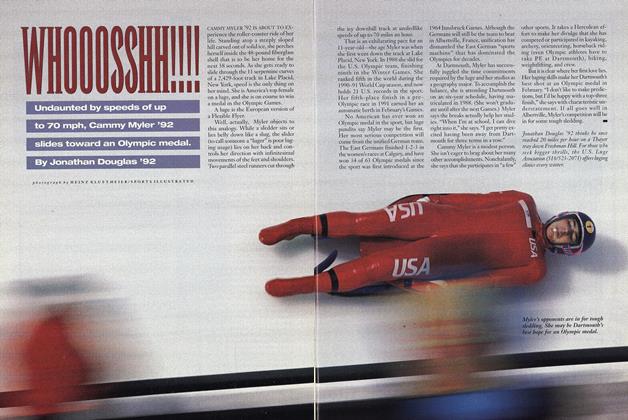

FeatureWHOOOSSHH!!!!

December 1991 By Jonathan Douglas '92 -

Cover Story

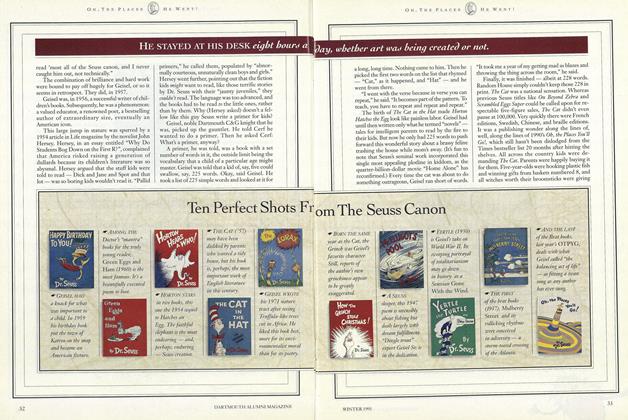

Cover StoryTen Perfect Shots From The Seuss Canon

December 1991 -

Cover Story

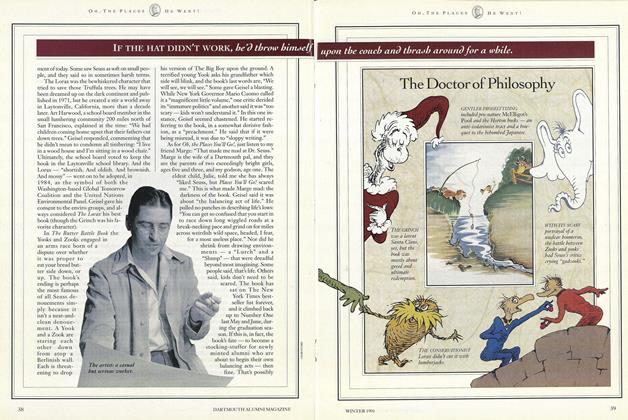

Cover StoryThe Doctor of Philosophy

December 1991 -

Cover Story

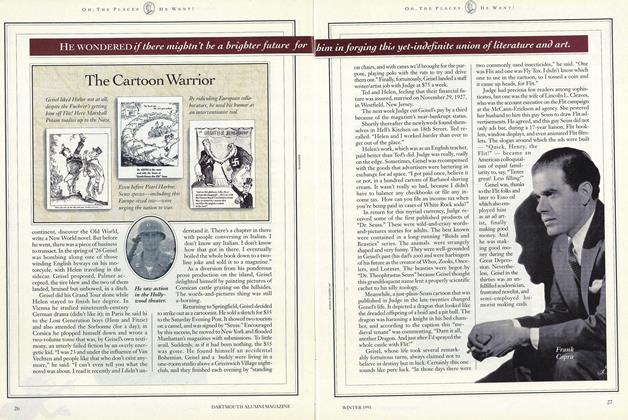

Cover StoryThe Cartoon Warrior

December 1991 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe 'Lanterns' Brightest Light

December 1991

Karen Endicott

-

Article

ArticleThe Corset Controversy.

October 1993 By Karen Endicott -

Article

ArticleThe Daughters of Eve

October 1993 By Karen Endicott -

Article

ArticleFilling The Power Vacuum

June 1994 By Karen Endicott -

Article

ArticleVirtual Munchausen

DECEMBER 1998 By Karen Endicott -

CLASSROOM

CLASSROOMPreparing for a Life in the Pits

Nov/Dec 2000 By Karen Endicott -

Classroom

ClassroomThe Art and Science of Group Dynamics

Nov/Dec 2002 By Karen Endicott