Preparing for a Life in the Pits

Student conductors must strive to develop an intellectual view of what they want to hear.

Nov/Dec 2000 Karen EndicottStudent conductors must strive to develop an intellectual view of what they want to hear.

Nov/Dec 2000 Karen EndicottStudent conductors must strive to develop an intellectual view of what they want to hear.

LINDSAY MACINDOE '01 steps up to the podium. One of seven students in music professor Melinda O'Neals course Music 70: "Conducting," Maclndoe is about to conduct her final project, the overture to Mozart's The Marriageof Figaro. Though her ensemble consists of two professional pianists, she describes aloud the symphony orchestra she sees in her mind: violinists to her left, cellos to her right, woodwinds and brass toward the middle and back. She looks at her pianists, raises her baton, takes a breath and gives the first downbeat. The music spills forth. When they finish this runthrough, Maclndoe says she'd like them to play "subito piano"— suddenly softer—at a particular measure. "It's hard to play that on the piano," she acknowledges. "How about going lighter?"

"Yes! Right!" O'Neal calls out.Then the professor, a seasoned conductor of Dartmouth's Handel Society and several other ensembles, offers Maclndoe a tip on how to elicit the sound she wants: "They'll play lighter if you move less. Don't slouch. The pianist's hands are going to collapse if you crouch. She's not going to play as well."

Maclndoe straightens her posture and begins the overture again. This time she remains erect and lets her baton bounce lightly. There is an audible springiness to the music. "Yes! That's right!" O'Neal applauds. "Remember how it feels."

Maclndoe has just experienced what the world's finest conductors count on at each rehearsal and performance: that through every thought, explanation and nuanced gesture, the conductor makes or breaks the sound of music. Audiences—whether at live performances or listening to a CD—may not be consciously aware of the conductor's effect, but they can hear and feel the difference between uninspiring noise and music with soul.

"The conductor is the one whom the composer has most to fear," warned composer and conductor Hector Berlioz in the early 19th-century, when conducting was a new art. (Prior to the musical complexities of 19th-century works, conductors as we know them were not needed.) "A composer must consider himself happy if his work has not fallen into the hands of a conductor who is both incapable and hostile," Berlioz continued. "Under such direction the noblest and boldest inspirations can appear ridiculous, enthusiasm can be violently brought down to earth; the angel is robbed of his wings."

Although the musical stakes for a conductor may seem higher than a soprano's high C, O'Neal lets her students in on a little secret: "Some books imply that we must be godlike to be conductors. Don't take that too seriously Conducting is not impossible."

In fact, that is the overarching theme of Music 70, which O'Neal created in 1979. "There are so many misconceptions about conducting—that it's about looking good in front of a group, that it's a power thing," O'Neal explains. "Really, it's all about preparation: learning the score, developing an intellectual point of view about the piece, preparing rehearsal strategies." By necessity her course is hands-on. There is no way to learn conducting other than by doing it.

During the earliest days of class, students practice a basic but crucial physical skill: using a lightweight, wooden baton to mark various metrical patterns. Holding their batons (which cost about $17) in their right hands, they direct the stick down and then quickly up for one beat per measure; diagonally down to the right, then back up for two beats per measure; triangular for three; down, left, right and up for four per measure. Though everyone in class is already a skilled musician—each plays at least two instruments, a few also sing—the technique comes awkwardly. They'll work on it throughout the term, even as they build other physical skills, such as using the left hand to cue musicians about entrances, cut-offs, dynamics, tone and dramatic character.

With those conducting basics in hand, students begin conducting one another in short musical pieces O'Neal has selected. She expects students to come to class prepared to conduct, which means a lot of prior work. Students have to read up on the historical period in which the music was written. ("If you want to truly understand a piece, you need to understand what's going on in other arts at the time," explains Andrew

Pease '01, clearly absorbing O'Neal's point.) Students also analyze each musical score in detail. O'Neal recommends that they listen to recordings to introduce themselves to the piece, then ignore the recordings and work out their own interpretations. To that end, she holds weekly one-on-one score-reading sessions with students, in which she helps them learn to identify harmonic struc tures, imagine the tone colors each instrument would bring to the sound and develop a sense of the music's expressive possibilities.

Then O'Neal adds another dimension to the students' conductorial toolkit. For their midterm and final projects, they must conduct a vocal and an instrumental work of their own choosing from the classical repertoire. They have to round up student musicians, find rehearsal space and schedule rehearsals. "Professionals," O'Neal tells them, "schedule four hours of rehearsal plus a dress rehearsal for every hour of music performed. For choral works sung in French, the rule is to allow three times as many rehearsals as forworks in English." Students also have to work out their musical goals—intonation, musical phrasing, balance of sound—for each rehearsal. "Our ultimate objective is to communicate musical ideas that make sense to the audience, not just the musicians," O'Neal reminds the class.

Each project conducted in front of the class becomes a lesson in itself. When Carmen Flores '00 tries to figure out how to prevent a soprano from singing sharp, O'Neal suggests that the soprano stand next to the bass instead of the alto so she can tune her pitches to the deeper ones. After the rehearsal, when the singers had left, O'Neal gives Flores some extra advice: "Sometimes when you point out that a singer is sharp, you can't get them to come back down. You often have to start again an- other day." When Pease conducts a Mendelssohn excerpt, O'Neal zeroes in on why his two pianists aren't playing together. "Your mind is buzzing, so your body is buzzing, giving them too many signals" she diagnoses. She prescribes a solution: "Put the stick down and conduct just thinking the music." As students encounter other problems on the podium, O'Neal doles out fixes: Sing the effect you want. Conduct phrases, not beats. Tempo can solve a lot of problems. Lighten your gestures; think "less is more." Experiment.

"You don't know the score well enough if it sounds like noise and you don't know how to fix it," O'Neal tells the class. "You have to be able to articulate the problem: whether someone is playing the wrong note, whether you're rushing the pace. It all goes back to a real, deep commitment to the score—and to not being afraid of it. You get to the point where you have to trust your ears and go with it."

Bringing students closer to that point is O'Neal's goal. "Students go through growth spurts," she explains after class. "You have to be patient. You have to teach the fundamentals and the essence of music making. You have to make sure they have the tools to deal with the score.Then you work with them to take them to the next level."

Over the years some dozen of O'Neal's students have gone on to become conductors. Others have reached O'Neal's more general goal for students: They become better musicians. "I never really knew the formal ideology behind conducting," music major Flores says at the end of term. "As a conductor, you're forced to lead other people, to have the vision. Professor O'Neal makes you feel that you can do it."

Mental Notes "Conducting is a mindthing," says Professor O'Neal, left,with Lindsay MacIndoe '01. "You picture the sound, then convey it."

COURSE: Music 70: "Conducting" PROFESSOR: Melinda O'Neal PLACE: Faulkner Recital Hall, three hours per week, plus rehearsals GRADE BASED ON: Class participation, two quizzes, two major conducting projects (one instrumental and one vocal) READING: The CompleteConductor by Robert W. Demaree and Don V. Moses (Prentice Hall, 1994)

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

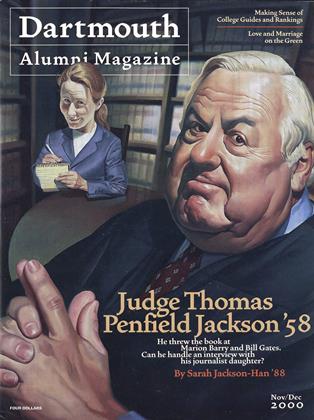

Cover StoryFather In Law

November | December 2000 By SARAH JACKSON-HAN ’88 -

Feature

FeatureAnd the Bride Wore Green

November | December 2000 By MEG SOMMERFELD ’90 -

Feature

FeaturePolitical Junkie

November | December 2000 By Jake Tapper ’91 -

Feature

FeatureWISDOM OF THE GUIDES

November | December 2000 -

Feature

FeatureOVER-RATED

November | December 2000 -

Feature

FeatureWHAT STUDENTS SAY

November | December 2000

Karen Endicott

-

Feature

FeatureTaking God's Word For It

APRIL 1990 By Karen Endicott -

Article

ArticleMaking the Walls Talk

June 1993 By Karen Endicott -

Article

ArticleArt in a Box

Winter 1993 By Karen Endicott -

Article

ArticleTied Up with Strings

December 1994 By Karen Endicott -

Article

ArticleThinking About 9/11

Jan/Feb 2002 By Karen Endicott -

Article

ArticleJapan's Ambivalent Story

OCTOBER 1988 By Mary Scott, Karen Endicott

Classroom

-

CLASSROOM

CLASSROOMHeaven and Hell in the Middle East

July/Aug 2002 By Alex Hanson -

CLASSROOM

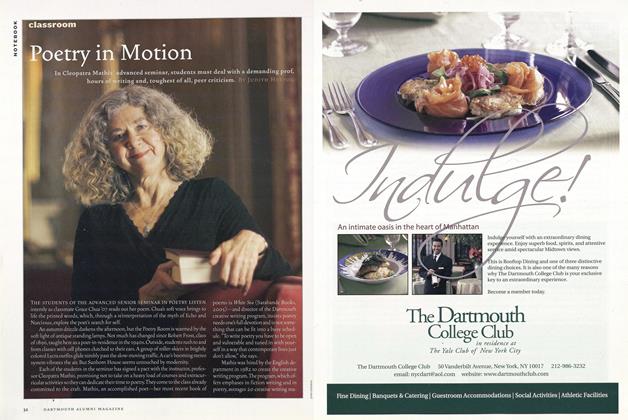

CLASSROOMPoetry in Motion

May/June 2007 By Judith Hertog -

CLASSROOM

CLASSROOMHe Says, She Says

Sept/Oct 2008 By Judith Hertog -

CLASSROOM

CLASSROOMOutside The Box

NOVEMBER | DECEMBER 2013 By JUDITH HERTOG -

CLASSROOM

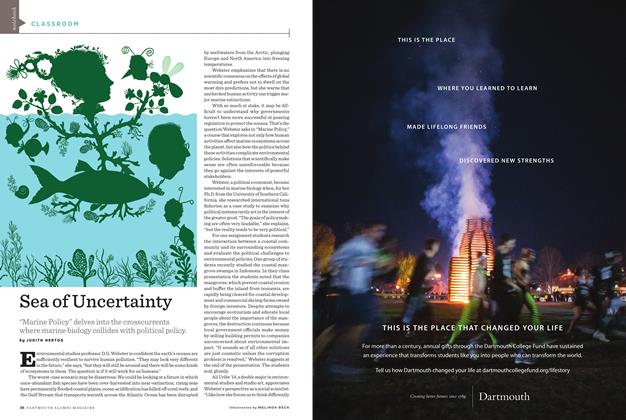

CLASSROOMSea of Uncertainty

MAY | JUNE 2014 By JUDITH HERTOG -

CLASSROOM

CLASSROOMThe Answers Are Blowin’ in the Wind

Jan/Feb 2001 By Karen Endicott