The Art and Science of Group Dynamics

Are you a deviant? Are you authentic? Professor Ruth Wageman helps sudents find the answers.

Nov/Dec 2002 Karen EndicottAre you a deviant? Are you authentic? Professor Ruth Wageman helps sudents find the answers.

Nov/Dec 2002 Karen EndicottAre you a deviant? Are you authentic? Professor Ruth Wageman helps sudents find the answers.

JUST BEFORE 8:45 THE first morning of the term, professor Ruth Wageman bursts through the door of 202 Moore Hall with a hearty "Good morning!" A few of the 30 or so students mumble a greeting. "Oh that was pathetic. Good morning!" Wageman says more pointedly. This time the whole class responds.

Satisfied, Wageman introduces herself. She is a professor at Tuck School of Business, and this is her first time crossing over to the psychology department to teach this undergraduate course, "Psychology and Business." "I'm basically a social psychologist," she says, adding that she focuses on how individuals and groups behave in organizations, particularly businesses.

Wageman turns to the first of many real-life case studies she'll present to the class. An aircraft in a holding pattern runs out of fuel just short of the runway and crashes. According to the National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) report, the crew was fully trained and qualified, the aircraft had been properly maintained and fuel consumption was normal. Searching for other clues, Wageman reads aloud from the NTSB transcript of the cockpit voice recorder. The last words of the pilot, first officer and flight engineer reveal that the crew encountered a catastrophic failure to communicate.

The professor fills the class in on a major factor affecting interactions in the cockpit: Airline crews are assigned randomly. Although this maximizes flexibility for the airlines, random rostering produces crews that have never worked together before. These ad hoc groups lack the interpersonal skills and knowledge that long-standing teams possess. And crews with no experience working together are at a disadvantage in an emergency, when quick, coordinated action separates survival from doom.

The bottom line: Ignore the psychology of groups at your own peril.

Wageman introduces students to the numerous levels of social interactions that occur within organizations. She discusses how individuals influence each other, how individuals function in groups, how groups affect each other, and how leaders and followers influence each other. She takes real-world interactions, then presents various psychological theories that attempt to explain the behaviors. An expert in creating successful teams, Wageman deliberately includes examples that provide practical know-how the students can use to carry out the group research projects she requires.

Take motivation. "Motivation to do something is influenced by what individuals expect the outcome to be of a behavior," Wageman says, explaining "expectancy" theory. Wageman asks students how she could motivate them to come to class on time. The students have no trouble upping the consequences of coming late: The prof could stop the lecture when someone Enter , take roll or give a pop quiz at the beginning of class. The point, Wageman says, is to "increase the value an individual places on the outcome." (The lesson sticks. Hardly anyone arrives late the rest of the term.)

Turning to interactions between individuals (a.k.a. dyadic relations), Wageman again gives the students an exercise. She assigns half the class to write to their mothers about what they've been doing lately. The rest write to their best friends. Then she picks a couple of students to read their letters aloud. Not surprisingly, the letter to the friend chats about parties, friends, feeling disorganized and apathy toward seaching for a job, while the letter to mom emphasizes studying hard and acting responsibly. Wageman uses the predictable variations in the letters to illustrate pervasive patterns of interactions between individuals—interactions that range from the natural to the deliberate and that vary according to how forthcoming a person is or isn't.

According to Wageman, many people have trouble being forthcoming—what she calls "authentic." She demonstrates the problem with a challenge her students may well encounter during their group projects. "You're writing a paper with five or six others. One member does a bad job with his or her section. What do you do? What are your goals? What do you say?" Again the class divides into groups to thrash out answers. One group takes a deliberately sympathetic approach, another states flatly, "We can tell you didn't put in enough effort." Neither approach is authentic, Wageman points out. For one thing, "No one inquired if the person understood the assignment or how much effort was put in," she says.

She outlines how she would handle the conversation: "This is going to be an uncomfortable experience. I don't think this part of the paper is very good. It needs rewriting. You can set goals, then we can discuss them. We also can discuss what happened and how to solve the problem. I also want you to express your feelings about this." The ultimate goal, says Wageman, s for both parties to come out of the interaction committed to a solution.

The students aren't alone in needing guidance in authenticity. According to Wageman, a study by psychologists of more than 163 business meetings, broken down into more than 45,000 separate behavioral units, reveals that fewer than 25 percent of the behaviors could be classified as authentic. "No question, being authentic is hard," says Wageman.

Wageman introduces another Common problem involving an individual and a group, the case of a person regularly seeing things differently from the majority. Minority or deviant opinions can benefit a group, she says, by challenging "group think." Even if the minority view is proven wrong, it opens the group to other ways of looking at problems. But a group can also dismiss an idiosyncratic thinker, casting him into the role of institutional deviant. How do you avoid becoming the ignored deviant? One researcher, says Wageman, advises biding one's time before deviating; be a good group member, conform initially to group norms and display competence. Then minority views will be taken seriously. Another researcher, Wageman adds, advises deviating right away in order to establish a consistent, seemingly objective perspective. In this case, though, it helps to have at least one other person on your side so the group thinks the minority knows something.

By the end of the term, the class has heard the theories of dozens of researchers. They've examined data. They've followed Wageman as she has plotted graph after graph on the board. And they've completed their group projects. Some have studied the interactions of the Colleges safety and security officers and students. Others have studied various student governance groups. In the process, all have had to figure out how to work together to get the job done.

No doubt it helped that the professor provided the students with an extra social psych tool to deal with slackers—a kind of classroom version of Weakest Link: "If a group (here defined as two-thirds of its members) requests that an individual not receive credit for the report, we will comply."

And though no one fell back on that, Wageman observed after class, the group dynamics proved difficult for students. "They didn't handle issues of equitability well. It was hard for them to overcome politeness norms to confront each other," she says. "Some will conclude that working in groups is a bad thing."

But in a social world, working in groups is unavoidable, whether in a cockpit or a classroom. At least with some social psych under their belts, Wagemans students may be less likely to crash and burn when the going gets tough. a

Limited Seating Task groups work best when they have fewer than nine members, according to Wageman.

COURSE: Psychology44: "Psychology and Business" PROFESSOR: Ruth Wageman PLACE: 202 Moore Hall, three hours per week GRADE BASED ON: Group project, two exams and class participation READING: Handbook ofIndustrial and Organizational Psychology, Vol. 3, edited by Mrvin Dun- nette and Leaetta Hough (Consulting Psychologists Press); Groups ThatWork (and Those ThatDon't), edited by J. Richard Hackman (Jossey-Bass); numerous journal articles

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe Gatekeepers

November | December 2002 By JACQUES STEINBERG ’88 -

Feature

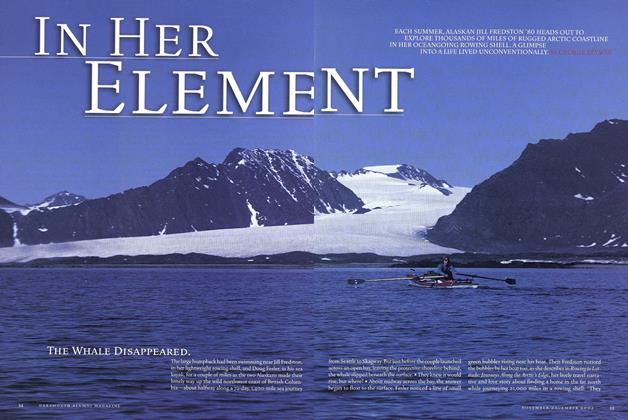

FeatureIn Her Element

November | December 2002 By GEORGE BRYSON -

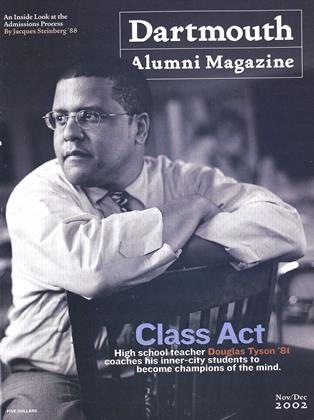

Cover Story

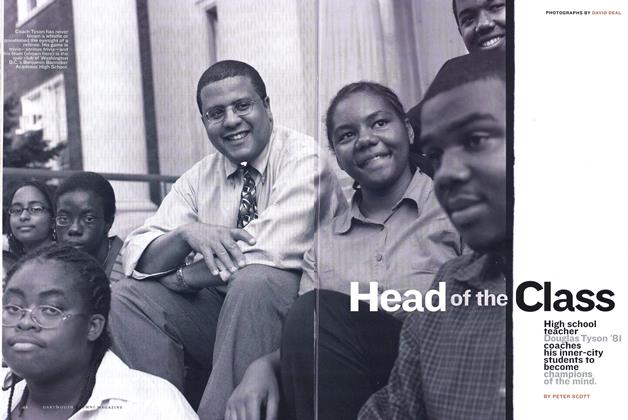

Cover StoryHead of the Class

November | December 2002 By PETER SCOTT -

Faculty Opinion

Faculty OpinionThe Iraq Question

November | December 2002 By Daryl G. Press -

Outside

OutsideThe Literature of the Logbooks

November | December 2002 By Madeleine Eno -

Article

ArticleSeen & Heard

November | December 2002

Karen Endicott

-

Feature

FeatureIs Vietnam Still Claiming Some of Us?

December 1988 By Karen Endicott -

Article

ArticleIran's Bum Rap

February 1993 By Karen Endicott -

Article

ArticleSound Words

FEBRUARY 1994 By Karen Endicott -

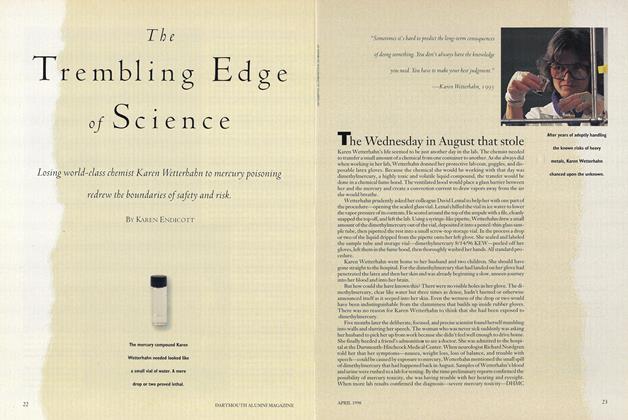

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe Trembling Edge Of Science

APRIL 1998 By Karen Endicott -

CLASSROOM

CLASSROOMFrom the Page to the Stage

Mar/Apr 2002 By Karen Endicott -

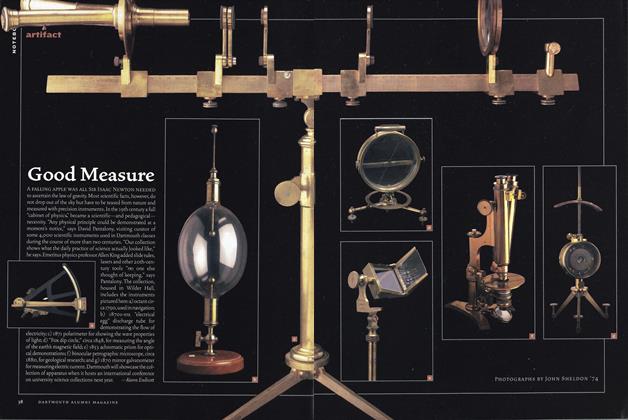

Article

ArticleGood Measure

Sept/Oct 2003 By Karen Endicott

Classroom

-

CLASSROOM

CLASSROOMGOOD VIBRATIONS

JULY | AUGUST 2025 By EMMA JOYCE -

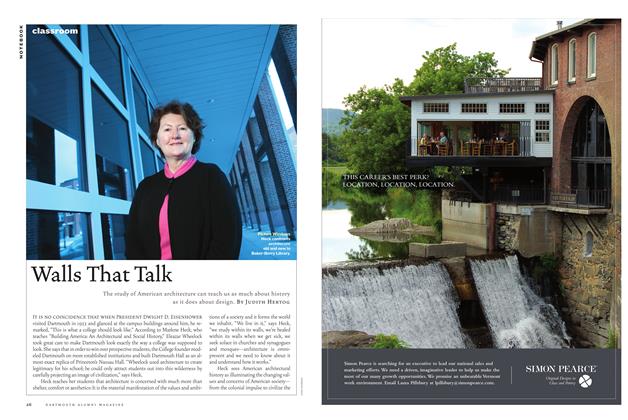

CLASSROOM

CLASSROOMWalls That Talk

May/June 2009 By Judith Hertog -

CLASSROOM

CLASSROOMRich Man, Poor Man

Sept/Oct 2011 By Judith Hertog -

CLASSROOM

CLASSROOMMaking A Case

July/Aug 2013 By Judith Hertog -

CLASSROOM

CLASSROOMWhen Nations Collide

SEPTEMBER | OCTOBER 2018 By JUDITH HERTOG -

CLASSROOM

CLASSROOMWhy the Play’s Still the Thing

May/June 2001 By Karen Endicott