'President John Sloan Dickey was a mentor of sorts for an entire institution

WHEN I THINK OF PRESIDENT John Sloan Dickey '29,1 think of the way in which literary critics refer to the daunting effect that great writers of the past often have on contemporary writers. The critics speak of "the anxiety of influence." I daresay that each of John Dickey's successors to the presidency of the College has experienced something of that anxiety, for President Dickey, more than any person at least since the Second World War, embodied Dartmouth's institutional purpose, its culture, its history, its spirit. He set a standard in wisdom and in energy, in compassion and in commitment —: for each of his successors to emulate.

At a time when we are celebrating Dartmouth's greatest mentors, it seems appropriate to think of two qualities that made President Dickey a mentor of sorts for an entire institution. These qualities are his vivid awareness of life and the world around him, and his unflagging belief that idealism must inform thoughtful and committed lives.

When I think of John Dickey, in all of his robustness, the first author who comes to my mind is not obviously Henry James, a sedentary individual of drawing-room delicacy. Yet, one of the most famous sentences that James ever wrote does seem apposite. In his essay "The Art of Fiction," James advised, "Try to be one of the people on whom nothing is lost."

John Sloan Dickey was such a man. Repeatedly, he encouraged Dartmouth students to "enlarge the quality" of their awareness, to notice more fully the world around them, and to leave personal selfishness behind.

Most importantly, he encouraged them to appreciate the unique nature of the Dartmouth experience an experience which celebrates Dartmouth's sense of place while concurrently broadening one's vision to further horizons; which encourages self-knowledge even as it liberates one from the provincialism of self; which captures the heart even as it schools the mind; which provokes intellectual skepticism even as it binds one in lifelong loyalty.

I am struck, too, by the fact that each of the achievements most closely associated with John Dickey flowed from an unapologetic idealism: his guiding perception of the unique mission of the American liberal arts college, a mission he defined as making students "whole in both competence and conscience"; the Tucker Foundation, which he founded in order to help students transform their idealism into committed action; and the Hopkins Center for the Performing Arts, which he envisioned as a bustling "agora of the arts."

Beyond these were the creation of the Great Issues course, designed to focus the attention of seniors on forces shaping the country and the world; the effort to infuse a global perspective into Dartmouth's every endeavor; the founding of Dartmouth's Equal Opportunity Program; the assembling of a distinguished faculty of teacher-scholars; the reinitiation of a full-scale M.D. program at the nation's fourth-oldest medical school; and personal service as vice chairman of President Truman's Committee on Civil Rights, which in 1947 published the seminal report entitled To SecureThese Rights. This remarkable harvest of achievements grew out of John Dickey's idealism his well-spring of faith in the progress of mankind and his fundamental belief in the dignity of individual men and women.

Speaking to freshmen at Moosilauke Ravine Lodge in September 1973, he said, "Dartmouth was founded out of an immense idealistic impulse. Today it's a little fashionable... to throw off idealism, but Dartmouth is here...because Wheelock was not afraid of ideals. Dartmouth had a dedicated purpose."

President Dickey insisted that that purpose involved leadership: "the cultivation of a man possessing both the will of a cooperative spirit and the competence of a free mind." And that remains Dartmouth's purpose today. In recounting his achievements as a son and servant of Dartmouth, and as an over-mentor of an entire generation of leaders, we can take quiet comfort from the certainty that succeeding generations of Dartmouth men and women will forever seek to match his stride.

This essay is adapted from a eulogy President Freedman gave at a memorial service for President Dickey in Rollins Chapellast April.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

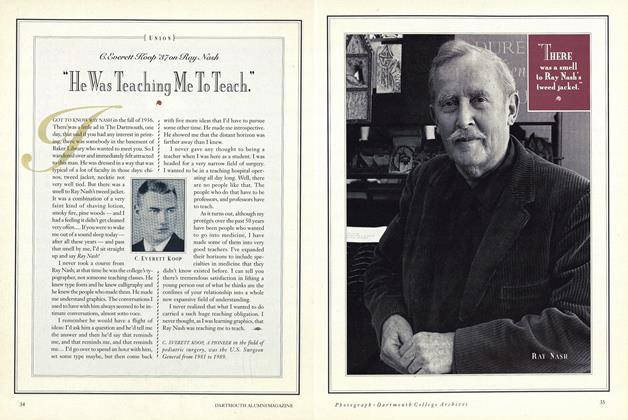

FeatureC. Everett Koop '37 on Ray Nash

November 1991 By Ray Nash -

Feature

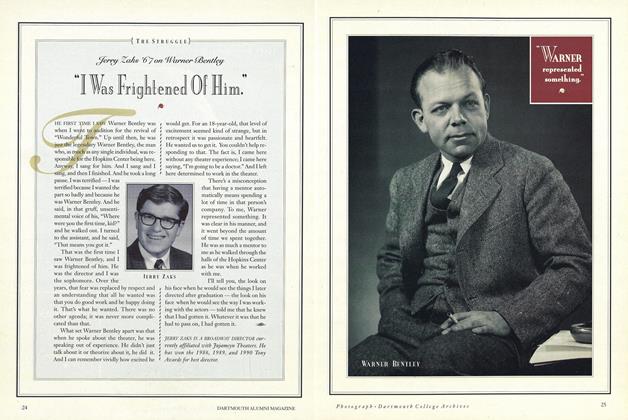

FeatureJerry Zaks '67 on Warner Bentley

November 1991 By Warner Bentley -

Feature

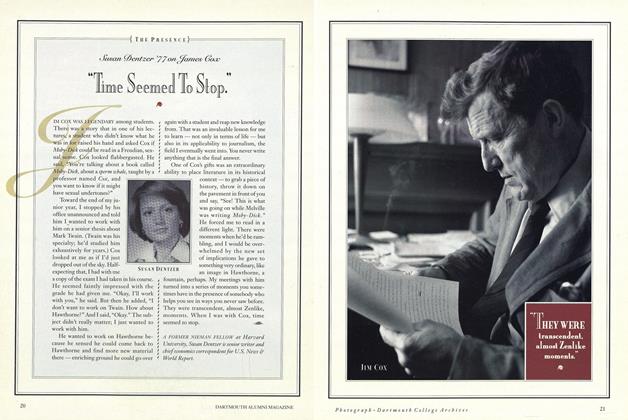

FeatureSusan Dentzer '77 on James Cox

November 1991 By Jim Cox -

Feature

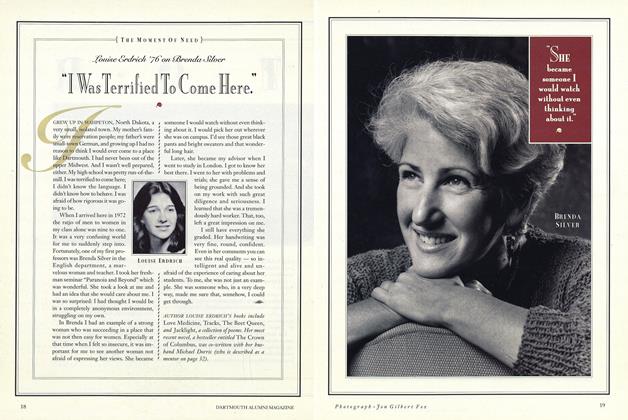

FeatureLouise Erdrich '76 on Brenda Silver

November 1991 By Brenda Silver -

Feature

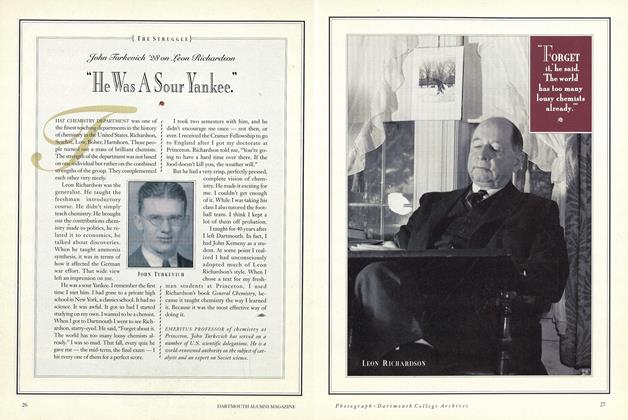

FeatureJohn Turkevich '28 on Leon Richardson

November 1991 By Leon Richardson -

Feature

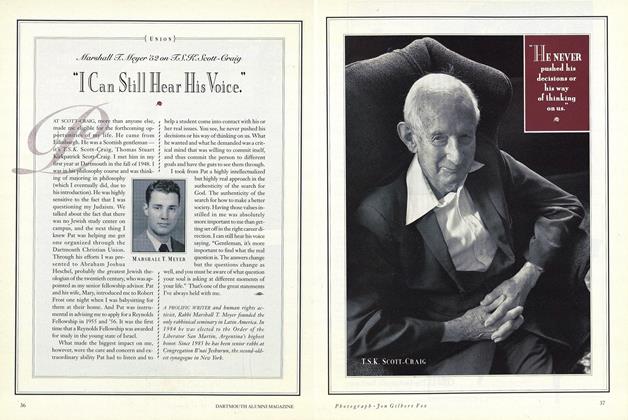

FeatureMarshall T. Meyer '52 on T.S.K. Scott-Craig

November 1991 By T.S.K. Scott-Craig

James O. Freedman

-

Article

ArticleTHE CONCEPT OF HEROISM

MAY 1991 By James O. Freedman -

Article

ArticleCompared to What

June 1992 By JAMES O. FREEDMAN -

Article

ArticleEssayists and Solitude

November 1994 By James O. Freedman -

Article

ArticleWhen Knowledge Cures

October 1995 By James O. Freedman -

Article

ArticleLibraries Unbound

JANUARY 1998 By James O. Freedman -

Feature

FeatureAn Honor, To a Degree

Sept/Oct 2002 By JAMES O. FREEDMAN