"Far from an official institutional statement, it was a personal, even idiosyncratic letter."

IT IS NOW THREE months since the class of 1996 arrived on the Hanover Plain. They came to Dartmouth from around the world, from 26 nations, from all 50 states and the District of Columbia, and from 815 secondary schools—1,088 individuals of intellect, idealism, and imagination. Nearly one-third are valedictorians or salutatorians; their records show them to be one of the most academically promising classes in Dartmouth's history.

In August I sent all the members of the incoming class a letter welcoming them to Dartmouth. Far from an official, institutional statement, it was a personal, even idiosyncratic letter offering a little advice and wishing them every satisfaction and success. I told them that as Dartmouth students they will have before them—in faculty and facilities-the best tools in the world with which to achieve a liberal education. Their task, I explained, was, as St. Thomas Aquinas wrote, "to contemplate and bring to others the fruit of your contemplation." No endeavor, at this stage in their lives, is more important. But they have limited time as undergraduates in which to do so—12 terms, 35 courses. I encouraged them to use that time wisely, demanding the best of themselves, taking the fullest advantage of all that the College has to offer.

I pointed out that they have just two summers and one other leave term before they are graduated, and I encouraged them to think of those three terms as that most treasured possession: time—time to work to contribute toward paying their educational expenses, time to read good books and to write in private moments of reflection, time to contemplate the values by which they wish to guide their lives, time to explore career possibilities, geographic locations, and life directions that beckon. Even as they begin their college careers, it is not too early to consider and discuss with others how they might best use these precious terms.

Finally, I encouraged them to take time for two activities that will help them profit fully from Dartmouth.

First, I said to each of them, take a quiet hour or two and set down-perhaps in the form of a letter to yourself—the reasons why you are coming to Dartmouth, the goals you hope to accomplish at college, and the values and aspirations that matter most to you as you begin this four-year segment of your life. These personal reflections, memorialized in writing for later review, may, in the months and years to come, serve as a fixed point against which to measure your growth and accomplishments—or perhaps a signpost to put you back on course.

Second, I advised, read good books. Among those that have mattered most to me are InvisibleMan by Ralph Ellison, one of the finest American novels since World War II; The Complete Stories by Flannery O'Connor, a brilliantly crafted set of fictions with grotesque and redemptive themes; A YellowRaft in Blue Water by adjunct Dartmouth Professor Michael Dorris, a moving coming-of-age novel of Native American life; JohnKeats by Walter Jackson Bate, a brilliant biography that depicts that youthful poet's extraordinary personal growth; The Children of Lightand the Children of Darkness by Reinhold Neibuhr, a dispassionate consideration of the relationship between human nature and democratic culture; and The Call of Stories by Robert Coles, a collection of thoughtful essays that explore the humane connection between teaching and the moral imagination.

The class arrived to a prematurely autumnal campus soon after they received my letter. Almost nine-tenths of the class came to Dartmouth early to participate in the DOC Trips. Orientation Week, which followed, afforded the students an opportunity to come to know their way around the College, its resources and hidden treasures. How much the students glean from this place will depend upon how well they know it and how much they themselves put into it. As Robert Frost, class of 1896, wrote in "At Woodward's Gardens," "It's knowing what to do with things that counts."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureKnow Your Place

December 1992 By George J.Demko -

Feature

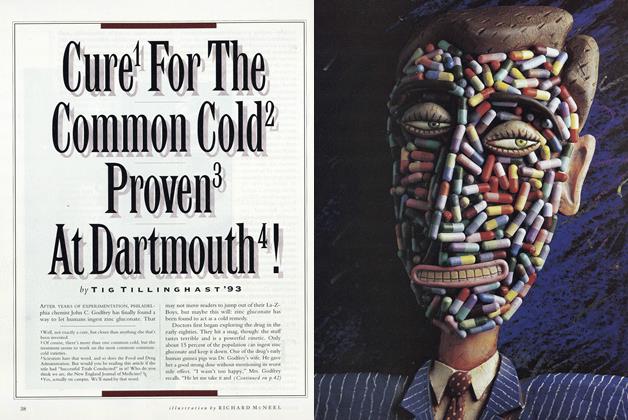

FeatureCure1 For The Common Cold2 Proven3 At Dartmouth4!

December 1992 By TIG TILLINGHAST '93 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe Library Culture

December 1992 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe Ether Library

December 1992 -

Cover Story

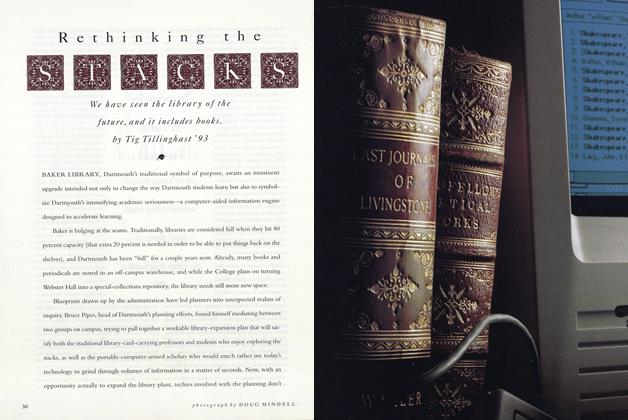

Cover StoryRethinking The Stacks

December 1992 By Tig Tillinghast '93 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryWith Hard-bound Books, Who Needs Digital?

December 1992

James O. Freedman

-

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorPresents Accounted For

June 1994 -

Article

ArticleCOACHES AND PRESIDENTS

OCTOBER 1990 By James O. Freedman -

Article

ArticleTHE SENSE OF PLACE

SEPTEMBER 1991 By James O. Freedman -

Article

ArticleON PERSONAL DISTINCTION

OCTOBER 1991 By James O. Freedman -

Article

ArticleThe Idealist a Leader

February 1993 By James O. Freedman -

Article

ArticleStaying Out of the Groove

SEPTEMBER 1997 By James O. Freedman

Article

-

Article

ArticlePRESIDENT HOPKINS PRAISES THE "WORK-HIS-WAY" STUDENT

January 1921 -

Article

ArticleGleanings

February 1935 -

Article

ArticleCommencement Dates

February 1937 -

Article

ArticleAssociate Dean at Tuck

MARCH 1972 -

Article

ArticleAll This And Coffee, Too

January 1976 By CLIFF JORDAN '45 -

Article

ArticleD.O.C. of Boston

January 1942 By Francis C. Ryder '50.