"Professors are entitled to feel that rapture, to recognize that their teaching will create a ripple of influence that will be felt in the lives of students years after graduation."

SOMEONE HAS ACCURATELY DEFINED A college president as a person who shuttles between God and Mammon. Long days are spent preaching the hallowed ideals of academe while seeking the financial means of bringing them into reality. It is only at night in my study (whose quiet usually belies Fraternity Row's unruly reputation) that I can give myself over to the professorial side of my vocation.

Few readers of this column will be surprised to hear that a college president's job is a demanding one. But the impression that many people have of faculty is less accurate. Viewed from outside, the life of a professor seems sheltered from everyday reality, a haven for those too delicate and sensitive to succeed in the workaday world. Few understand that the life of a professor is a difficult and lonely one. It is a life of privilege, to be sure. But it has its costs.

The first is the continuous straggle to learn afresh what remains fundamental about a discipline that is always evolving, while bringing that knowledge to life in the minds of new students.

One of the themes of Carl Sandburg's autobiography, Always the Young Strangers, is the renewal of society in every generation by the emergence of "young strangers"—young people who have the ability to lead their contemporaries to renew the values that sustain our culture. In the course of a semester, professors have only so many opportunities to reach those young strangers. A carelessly read term paper, a poorly conceived assignment, a flatly delivered lecture any shortcoming in our instruction—wastes an opportunity. That is why we must work for so many hours on courses we are teaching for the second, third, or even the twentieth time.

A second cost is tie struggle to compress a host of protean and unruly tasks into a single day. In the absence of a clear boundary separating vocation from avocation, teaching from scholarship, creative effort from routine chores, no block of time can be protected from a flood of conflicting but equally legitimate demands.

Consider the quandary created by three unscheduled hours between classes on a given afternoon. Should a conscientious professor spend those hours refining the next classroom presentation, checking on new library acquisitions, catching up with reading in professional journals, doing research for a new article, double-checking a dubious experimental result, drafting a committee report, conferring with students who need extra attention, writing letters of recommendation, preparing a budget for a grant application, or revising the syllabus for next semester's course? Indeed, those golden unscheduled hours, so apparently free in prospect, are in actuality already oversubscribed before the day begins.

A third cost—one that can never be paid in full—is the responsibility to create new knowledge, whether in the library, the laboratory, or the studio. Because the search for knowledge is open-ended, there can be no point of conscientious rest.

But just as the costs of a life of scholarship and teaching are largely invisible outside the academic community, so are its unique rewards. Surely the most substantial is what Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. called "the secret isolated joy of the thinker, who knows that, a hundred years after he is dead and forgotten, men who have never heard of him will be moving to the measure of his thought." Holmes called that satisfaction "the subtle rapture of a postponed power." At the close of long days of work, at the conclusion of long years of scholarly solitude, professors are entided to feel that rapture, to recognize that their teaching will create a ripple of influence that will be felt in the lives of students years after graduation.

Still, professors, like all others whose identity is closely tied to their professional achievements, also need immediate and tangible gratification. In a period of intensified competition for limited financial resources, presidents as well as professors must understand that the measure of the scholar's thought is the source of an institution's vitality and the standard by which it must judge itself. Nothing else, not even the most lavish favors granted by Mammon, has value except as a means to that end.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

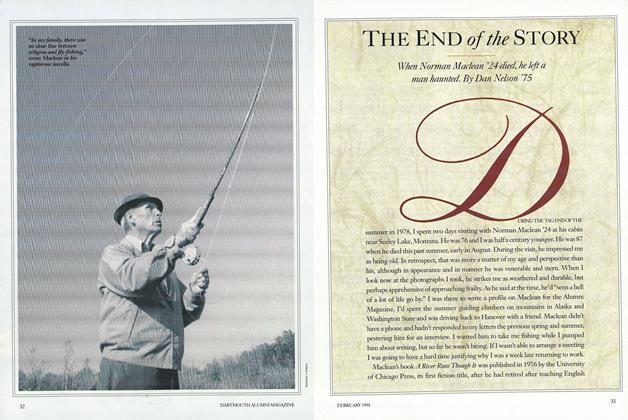

FeatureThe End of The Story

February 1991 By Dan Nelson '75 -

Feature

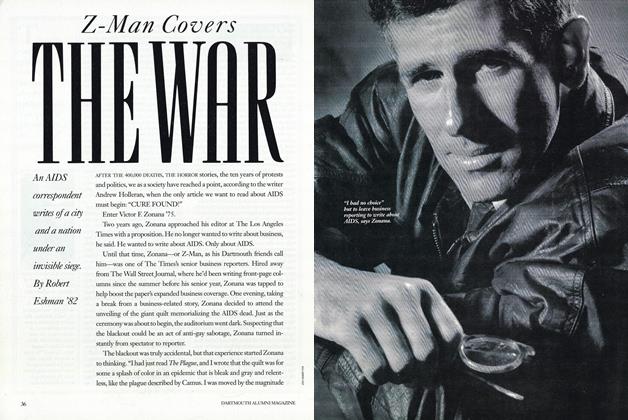

FeatureZ-Man Covers The War

February 1991 By Robert Eshman '82 -

Feature

FeatureOUR PASSIONATE PREFERENCE

February 1991 By Joseph D. Mathewson '55 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryNow For The Hard Part

February 1991 By Jay Heinrichs -

Feature

FeatureWHO OWNS DARTMOUTH?

February 1991 By Joe Boldt '32 -

Feature

FeatureIs Harvard Becoming More Like Dartmouth?

February 1991

James O. Freedman

-

Article

ArticleTHE PASSIONS OF SCIENCE

December 1990 By James O. Freedman -

Article

ArticleMY HEROES

MARCH 1991 By James O. Freedman -

Article

ArticleThe Human Scale

September 1992 By James O. Freedman -

Article

ArticleWorries of a President

May 1994 By James O. Freedman -

Article

ArticleObligations of the Educated

September 1995 By James O. Freedman -

Article

ArticleSkepticism and the Refined Mind

SEPTEMBER 1996 By James O. Freedman