From the Page to the Stage

An innovative drama class makes playwrights and actors out of undergraduates.

Mar/Apr 2002 Karen EndicottAn innovative drama class makes playwrights and actors out of undergraduates.

Mar/Apr 2002 Karen EndicottAn innovative drama class makes playwrights and actors out of undergraduates.

In the black-walled dimness of the Hopkins Centers Warner Bentley Theater, 15 students pull chairs into a semicircle and face their collective challenge: an empty stage. They have 10 weeks to write, rehearse and perform a play in front of a live audience.

"Lets get started," says visiting drama professor Kathleen Dimmick in a commanding voice that drowns out the students' pre-class chatter. Dimmick, a seasoned actor, director and dramaturge, and her longtime collaborator, playwright Quincy Long, have come to Dartmouth from New York for the summer to teach "Drama in Performance." They have brought along something crucial: an idea for a play.

No student could have been prepared for what Dimmick and Long had in mind. They wanted students to write a play about the nations proposed missile defense system—and link it to James Fenimore Coopers classic 1826 frontier tale, The Last of the Mohicans. But wait, there's more. The play would have production numbers, including several songs and a ballet (this was in the light-hearted days before 9/11). And the whole class would write all the elements of the play.

Dimmick and Long knew they had thrown down an enormous gauntlet, especially for many first-time actors. But this was for a class, not just for fun, and they wanted to challenge students. "In the past, students often wrote monologues, twocharacter plays or short plays written by two or three students. It's easier to put that kind of thing together," says Dimmick outside of class. "We didn't want that. We're sick to death of personal memoir plays. We wanted an ensemble piece."

But missile defense? It's not exactly an obvious theme for a play. "We wanted a contemporary issue that students could respond to," says Dimmick. "Missile defense was in the news. It seemed so out landish. President Bush's advisors are sober, sane people. We were curious why they were behind this," says Long.

Why add in The Last of the Mohicans? "Plays need an objective correlative-something to bounce the main idea off of," says Long. But what does Cooper s tale possibly have in common with star wars? "Each is about the domination of a frontier," says Dimmick.

As for production numbers: They would offer moments of comedy or melodrama and creative surprises in the pace of the play. "We wanted songs from the get-go," says Long.

With their work cut out for them, the students plunge into research. They read Coopers novel and bone up on ballistic missiles. The professors invite experts to clue students in on matters crucial to the play: government professor Allan Stam on star wars, English professor Don Peases take on Cooper's novel as an idealogical support for the relocation of Indians in 19th-century America, and film prof Michael Hanitchak '73 on stereotyped portrayals of Native Americans.

Even with this background, the students puzzle over how to jump from Native Americans to missile defense. They pitch ideas. They argue. It seems impossible for 15 people to agree on anything. Then Jeff Pauker '03, an economics major, presents an outline for a two-act play. It calls for a bumbling president from Texas who tries to sell the country on the need for missile defense via a puppet show based on The Last of the Mohicans. "The class was jazzed. There was some heat. It seemed fun," says Long.

The students break into groups to write the various scenes of the play. "Don't worry about different writing styles at this point. We'll work on the transitions later," Dimmick assures them. "You must have confidence that when you work in small groups you'll come up with something great." Long tries to ease anxieties. "This isn't something you're going to sell to Hollywood for big bucks," he reminds them, "but its a good idea for a play."

During the next two weeks the groups draft and revise scenes. They write song lyrics, choreograph a dance number and devise a marionette show. A music major volunteers to play the piano for the play. The students figure out their prop and costume needs. Finally, they,have a 41-page script caWed Mohican Missile Time.

Act I opens in a missile control center, where two technicians calmly type at computer consoles, launching missiles. The president, his advisors and his two teenaged daughters enter. The president lays out his fears about nuclear attack (expressed in part via a dream/dance number set to the music of Benjamin Britten's WarRequiem), then grabs his daughter s homework reading, The Last of the Mohicans. The book is about protecting the innocent, he says, adding, "I'm a simple man, people. I like simple stories. And so do the American people. And I believe there's a way to communicate the importance of missile defense to them through this story." His daughters suggest doing that through a puppet show. "What just happened?" one of his stunned advisors asks the others.

The puppet show happens in Act 11, set at an elementary school. Five puppeteers drag limp marionettes—played by students—onto the stage, then pull invisible strings to steer them through Coopers tale. The puppets break free, and—to make a long story short—an Indian rejects Coopers myth-making, and a generals daughter refuses to believe in missile defense. New scene: Pollsters quick-talk the schoolkids who saw the puppet show into support for star wars. Final scene: A happy president sings "Blue Skies" with his daughters as missiles dance into position to shield the first family from demonstrators.

Over the next few weeks Dimmick and Long direct the students through rehearsals. They work out the kinks as they go. Refining a central element of the play, they help Scott Rutherford '03 transform his portrayal of the president from a caricature to a character—a decent guy who loves his daughters, respects his advisors and cares about his country. "He has to seem real to us," Dimmick says. She and Long coach Rutherford to sound less like a stand-up comic delivering one-liners. "When you come to a period, don't let the momentum die. Don't let the energy drop," Long tells him.

At each rehearsal the profs take notes and offer advice. After one run-through, Dimmick seats herself onstage and reads out her list: "Almost everyone needs to work on volume; focus your lines out. Keep opening up to the audience. You need to know your lines cold. You need to get the rhythm of the cue line into your line; that's how the comedy will get its rhythm."

In addition to critique, there's encouragement. "That line is getting better," Long tells Kamil Walji '03. "It's all that practice," Walji replies. "That's what the theater is—practice," says Dimmick.

Finally it is opening night, the first of two performances. Some 50 people sit in the audience. Several are friends of the cast members. Others are members of the New York Theatre Workshop, which is in residency at the Hop. The lights go up onstage and something happens: The play comes together. The actors get most of their lines and their comic timing right. They sing and dance with gusto. The play's absurdities get laughs. When the applause comes, it's more than just polite.

After a second and final performance, the cast meets with members of the New York Theatre Workshop and Dartmouth's theater department for a post-mortem. "You made me laugh and you made me think," a theater department administrator tells the students. "It's unusual to have substance in plays these days, even rarer to do political satire," comments one New York Workshop member. The students, still sky-high, speak up as well. "I was completely shocked it came together. We had 15 scripts at first. It was so frustrating. We spent the whole time fighting about everything. We had to take the punches and roll with them," says Benjamin Mills '03. "The biggest thing I got out of this class was the ensemble experience. We played off everyone's talents," says Walji.

In her Hop office at the end of the term, Dimmick reflects on her evolving view of the impact of such collaborations. "I now firmly believe that for students to be able to work together on an ensemble piece is extremely important," she says. "Students today can have an oddly intense attachment to isolation, aided by their computers. The play encouraged them to collaborate, as painful as that is. They had to all do it together. That's valuable not just as theater but as a human activity."

Show Biz Theater pros Long andDimmick (at right) lead studentsthrough a "puppet show" rehearsal.

COURSE: Drama 65: "Drama in Performance" PROFESSORS: Kathleen Dimmick and Quincy Long PLACE: Warner Bentley Theater, five hours per week, plus rehearsals GRADE BASED ON: Attendance and participation READING: The Last ofthe Mohicans by James Fenimore Cooper

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

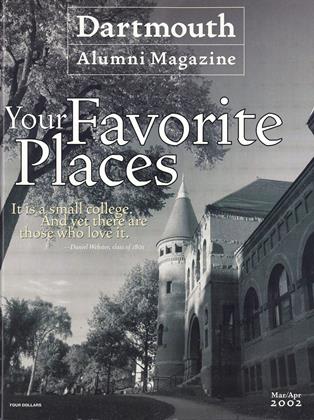

Cover Story

Cover StoryFavorite Places

March | April 2002 -

SEEN AND HEARD

SEEN AND HEARDNewsmakers

March | April 2002 -

PERSONAL HISTORY

PERSONAL HISTORYMeasure of the Mind

March | April 2002 By Robbing Barstow ’41 -

Article

ArticleEarly Decision

March | April 2002 By President James Wright -

Class Notes

Class Notes1980

March | April 2002 By Wade Herring, Carol Willard -

Class Notes

Class Notes1987

March | April 2002 By Jonathan Silverman

Karen Endicott

-

Article

ArticleHistory Professor Douglas Haynes

February 1993 By Karen Endicott -

Article

ArticleProfessor Katharine Gingrass-Conley:

May 1993 By Karen Endicott -

Article

ArticlePatient Talk

September 1993 By Karen Endicott -

Article

ArticleHISTORY THAT WON'T FLY

May 1995 By Karen Endicott -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorYou could say a woman started it all.

MARCH 1997 By Karen Endicott -

CLASSROOM

CLASSROOMCode of Life, Codes of Conduct

Sept/Oct 2000 By Karen Endicott

Classroom

-

CLASSROOM

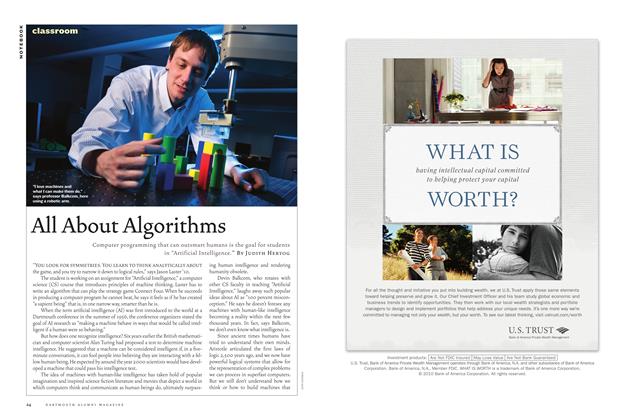

CLASSROOMAll About Algorithms

Sept/Oct 2010 By Judith Hertog -

CLASSROOM

CLASSROOMReality Show

NovembeR | decembeR By JUDITH HERTOG -

Classroom

ClassroomLearning By Doing

May/June 2004 By Julie Sloane ’99 -

Classroom

ClassroomThe Human Condition

Sept/Oct 2004 By Julie Sloane ’99 -

CLASSROOM

CLASSROOMPreparing for a Life in the Pits

Nov/Dec 2000 By Karen Endicott -

CLASSROOM

CLASSROOMWhy the Play’s Still the Thing

May/June 2001 By Karen Endicott