"By transcending themselves in their work, they found themselves again in the human community beyond."

WHEN TALKING WITH ALUMNI, I AM often struck by the personal nature of their memories of this place. As often as not, the stories alumni tell me have to do with the classroom, and the education they received from professors that went beyond courses. They speak to me of Professor of Sociology Emerita Elise Boulding, whose work in war and peace studies recently

earned her a nomination for the Nobel Prize; of the late Professor of Government Eugen Rosenstock Huessy, who developed a rich moral philosophy in the face of rising fascism; and of Walter Stockmayer, Albert W. Smith Professor of Chemistry Emeritus, who considered teaching as important to his life as his ground breaking work in polymers.

In short, they speak to me of academic heroes men and women who transcended their roles and were living examples for the moral lives of their students.

Heroes set standards for what it means to be a whole human being. I would like to tell you about two men who have been exemplars for me, who have been a source of my own vision of what the Greeks called exercising vital powers along lines of excellence.

One of these persons was my teacher at Yale Law School, Alexander M. Bickel, whose untimely death in 1974 is still an occasion for mourning. The other was my first employer, Thurgood Marshall, the leading civil rights lawyer of his generation.

Alexander Bickel was a teacher and scholar, a man of the book, an elegant intellectual who challenged and deepened our understanding of the function of law in a democratic society. Thur good Marshall was a pragmatic lawyer and earthy tactician, a dynamic mobilizer of men and women, a man of action who devoted his extraordinary talents to the most important law-reform effort of the twentieth century.

Professor Bickel advanced the law by the development of theory. Justice Marshall advanced the law by the perfection of practice. Each, in his own way, addressed the larger, humane questions that infuse law and life with significance.

From Alexander Bickel I learned, as he had learned from Edmund Burke, that adherence to the time-tested processes of the legal order, however frustrating they may sometimes seem, is more important to the practice of statecraft than is the achievement of any momentary political result. Justice Marshall taught me the indispensability of legal craftsmanship and the moral obligation to put that craftsmanship in the service of a significant public cause. In his case, that cause was the achievement of an integrated society, based upon the central value of our legal and political system equal justice for all citizens. Through his actions as well as his words, Justice Marshall taught me that a citizen's finest opportunity is not to make money and not to seek fame, but to ally both self and talents with an idea whose time has come. Alexander Bickel and Thur good Marshall represent two different strands in American culture the contemplative and the active strands that we should admire in equal measure.

Both of these men dedicated themselves to public lives of effective citizenship and to the achievement of a more just society. Both refined their private selves by wide reading and never-ending reflection upon the nature of a democratic commonwealth and of a free people's institutions. By mastering their own discipline, both men transcended it. By transcending themselves in their work, they found themselves again in the human community beyond.

Professor Bickel and Justice Marshall teach us, by their example, that the processes of managing a democratic society and of conducting a moral life are each dynamic ones. They are processes that require a continuing dialogue about which of our inherited values are bedrock and which are merely convenient and conventional a dialogue between the generations that have come before and our own generation; a dialogue between our own generation and the generations that will come after; a dialogue between our public selves and our private selves.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

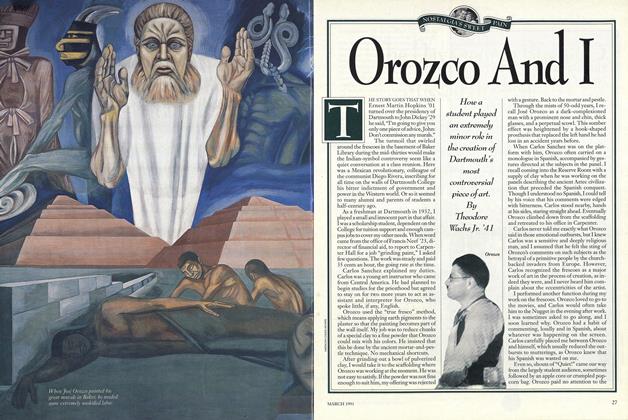

FeatureOrozco And I

March 1991 By Theodore Wachs Jr. '41 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryMiraculously Builded In Our Hearts

March 1991 By Judson D. Hale '55 -

Feature

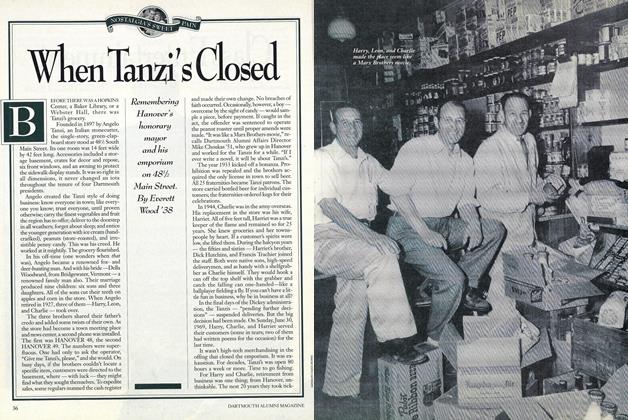

FeatureWhen Tanzi's Closed

March 1991 By Everett Wood '38 -

Feature

FeatureAn Unofficial (And, For That Matter, Not Altogether Pertinent) History of Dartmouth

March 1991 -

Feature

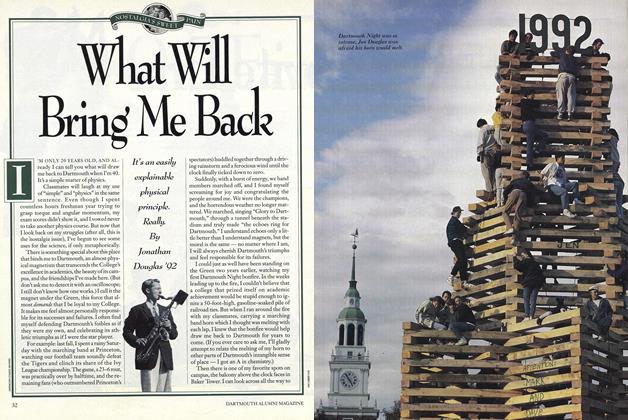

FeatureWhat Will Bring Me Back

March 1991 By Jonathan Douglas '92, Richard Hovey -

Feature

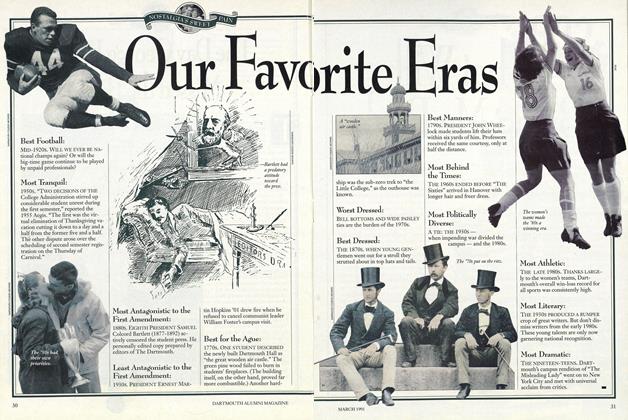

FeatureOur Favorite Eras

March 1991

James O. Freedman

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryIs "The College" a College?

December 1988 By James O. Freedman -

Feature

FeatureHONEST TO GOD ACCOMMODATION

OCTOBER 1991 By JAMES O. FREEDMAN -

Article

ArticleA Comprehensive Overhaul

October 1992 By James O. Freedman -

Article

ArticleThe Idealist a Leader

February 1993 By James O. Freedman -

Article

ArticleNothing Less Than a Hero

April 1993 By James O. Freedman -

Article

ArticleTowering Silences

APRIL 1997 By James O. Freedman

Article

-

Article

ArticleTHE TIE THAT BINDS A COLLEGE CLASS

January 1917 -

Article

ArticlePRESIDENT LOWELL'S RESIGNATION

January 1933 -

Article

ArticleHall of Famer

APRIL 1983 -

Article

ArticleAbout Twenty-Five Years Ago

December 1932 By Hap Hinman '10 -

Article

ArticleThayer School

MARCH 1972 By J.J. ERMENC -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

MAY 1971 By JOEL ZYLBERBERG '72