Aging Growing older,athletes tend to move in one of two directions: a little more wistful, or a little more wise.

SOME ARE CONTENDERS still: training for Olympic teams, doing what's never been done, run, climbed, or considered by the rest of us. To those on that leading edge, these thoughts may not mean much. They're offered instead to anyone who sweats without recognition and wonders why: the mass of us who still lead lives of labored respiration.

AT DARTMOUTH THE ISSUE (or so it seemed) was mind over matter. In pursuing sport, we found ourselveson hard granite rock face, on smooth water, on the boards, on the field and on the track, in the air and on ice and unforgiving snow. In our elemental struggles we experimented with the effects of oxygen deprivation at altitude, of lactic acid on muscle fiber, of bodies in motion through time and over distance.

We found creative, intricate ways to hurt ourselves on a regular basis. Whether we chose the camaraderie of organized sport, or a solitary pursuit, or the bacchanalia of the Beta basement, we learned quickly that bodily pain encourages the brain to produce beta endorphins: those morphine like substances that, more than making pain worth bearing, just about make life worth living. We came to believe, rightly or not, that there is no pleasure without pain.

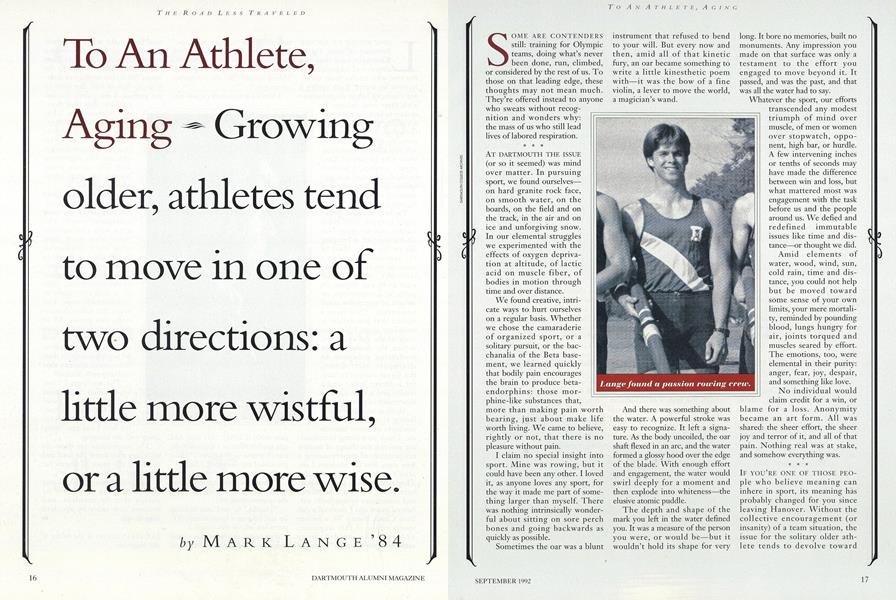

I claim no special insight into sport. Mine was rowing, but it could have been any other. I loved it, as anyone loves any sport, for the way it made me part of something larger than myself. There was nothing intrinsically wonderful about sitting on sore perch bones and going backwards as quickly as possible.

Sometimes the oar was a blunt instrument that refused to bend to your will. But every now and then, amid all of that kinetic fury, an oar became something to write a little kinesthetic poem with—it was the bow of a fine violin, a lever to move the world, a magician's wand.

And there was something about the water. A powerful stroke was easy to recognize. It left a signature. As the body uncoiled, the oar shaft flexed in an arc, and the water formed a glossy hood over the edge of the blade. With enough effort and engagement, the water would swirl deeply for a moment and then explode into whiteness the elusive atomic puddle.

The depth and shape of the mark you left in the water defined you. It was a measure of the person you were, or would be—but it wouldn't hold its shape for very long. It bore no memories, built no monuments. Any impression you made on that surface was only a testament to the effort you engaged to move beyond it. It passed, and was the past, and that was all the water had to say.

Whatever the sport, our efforts transcended any modest triumph of mind over muscle, of men or women over stopwatch, opponent, high bar, or hurdle. A few intervening inches or tenths of seconds may have made the difference between win and loss, but what mattered most was engagement with the task before us and the people around us. We defied and redefined immutable issues like time and distance or thought we did.

Amid elements of water, wood, wind, sun, cold rain, time and distance, you could not help but be moved toward some sense of your own limits, your mere mortality, reminded by pounding blood, lungs hungry for air, joints torqued and muscles seared by effort. The emotions, too, were elemental in their purity: anger, fear, joy, despair, and something like l ove.

No individual would claim credit for a win, or blame for a loss. Anonymity became an art form. All was shared: the sheer effort, the sheer joy and terror of it, and all of that pain. Nothing real was at stake, and somehow everything was.

IF YOU'RE ONE OF THOSE People who believe meaning can inhere in sport, its meaning has probably changed for you since leaving Hanover. Without the collective encouragement (or insanity) of a team situation, the issue for the solitary older athlete tends to devolve toward mind over does it matter.

It does, of course. Time and distance still conspire, but work their pain more privately. Now years and many miles have come between our present selves, the events we survived, and the teammates and coaches we shared them with. And yet somehow we don't really grow further apart at least not yet, and maybe not ever.

I rowed a single scull for a while after college, but never found the passion that I'd known in crews. Maybe it was because no one else was counting on me. The stakes didn't seem as high, the effort didn't matter as much. But what remained was something entirely new—a sense of play unthinkable in competitive circles.

Being lucky enough to live near a river with the office upstream in Washington, D.C., I rowed a scull back and forth to work for a while. No traffic. It was worth renting racks in two boathouses to glide underneath the fuming cars on the 14th Street Bridge in the morning, and past floodlit monuments at night.

For many of us, that sense of play still grows. There are new skills to be learned now, new ways to hurt yourself. Roller skiing, mountain biking, rockclimbing gyms in the winter's dark, skurfing (surfing on a ski boat wake), bungee-jumpingentire sports (well, pastimes) have emerged in the time since most of us did from Dartmouth. We go out. We learn them. Not with the same facility, maybe, but with at least as much enthusiasm, if bruises bear witness.

I've been bounced around the Columbia River gorge on a sailboard, rollerbladed up Colorado mountain passes, been beaten up in a triathlon, got saddle-sored on a bicycle across most of two continents, nents, and endured a wager that I could get up on a snowboard behind a ski boat in Florida and such tales pale beside those my friends can tell.

This sense of play in sport is something many of us never knew before. The whole thing is still some kind of achievement concept, but we have more excuses to achieve less now.

Injuries happen. We don't always remember how, and we don't recover quite as quickly. We use more liniment. Joe Namath speaks to us in ways he never did before. He promises to ease our pain. We actually come close to taking those ads for the "Abdominizer" seriously. Jane Fonda's starting to look pretty good. These are bad signs.

We talk more of a knee surgery or a shoulder injury than about any Fearful Opposition as though the body's deterioration is the real opponent. We watch with interest the emergence of new kinds of orthopaedic armor, knee braces, prescription protective eyewear all harbingers of our daily disability. Maybe we're just becoming differently abled, but I doubt it.

We bump into another Olympic year always a reminder of how good the best really are, and the best excuse there is to be a spectator. Skiers fly by in icy blurs of speed, sprinters explode out of the blocks so hard the earth may almost move, tiny gymnasts stubbornly bornly refuse to be overwhelmed by the gravity of their situation.

The couch threatens to overwhelm us. So we continue to go out and prove to ourselves, whether or not anyone else knows or cares, what it means simply to strive. The motivation is self-generating. We are all prime movers now.

In spite of a culture that encourages the avoidance of pain, we still plan vacations where much of our purpose is to hurt ourselves. In an era of sugar substitutes, spouse equivalents, and steroids, we still prefer to have some pain with our gain—still trying to live some significant part of our lives the hard way.

Muscles forget what minds remember. The oxygen uptake, VO2 max, glucose metabolism all that we used to take for granted takes just slightly longer now. The kick takes longer to wind up, the lactic acid longer to dissipate. But at least we can still count on our little friends the betaendorphins.

Growing older, athletes tend to move in one of two directionseither a little more wistful, or a little more wise. You begin to wonder whether much of your work is writ on water. Illusions of permanence give way to the beginnings of acceptance. Time is still the enemy, but it's measured not in the sweep of second hand, it's measured in years, and it throws a longer shadow.

We struggle half laughing at ourselves against this tyranny of time, this despair of distance. Time and distance: those are the terms. They're all we have. And so we give all we can, give until it hurts. And hope it is enough. a

Lange found a passion rowing crew.

Time IS STILL THE ENEMY, but it's measurednot in the sweep of secondhand, it's measured in years.

A former White House speech-writer, Mark LANGE now freelances andsweats in Boulder, Colorado.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureSecond Chances

September 1992 By Mary Cleary Kiely '79 -

Feature

FeatureFishing The River For A Monument

September 1992 By John Scotford '38 -

Feature

FeatureCommunion With The High Places

September 1992 By Andrew Daniels '85 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryChoices

September 1992 By Jay Heinrichs -

Article

ArticleDr. Wheelock's Journal

September 1992 By "E. Wheelock" -

Article

ArticleDEATH and DYING

September 1992 By Professor Sergei Kan

Features

-

Feature

FeatureInternational Catalyst

FEBRUARY 1967 -

Feature

FeatureHONORARY DEGREE CITATIONS

JULY 1972 -

Cover Story

Cover StorySartorial Splendor

April 1981 -

Feature

FeatureThe 1958 Commencement

July 1958 By C.E.W. -

Feature

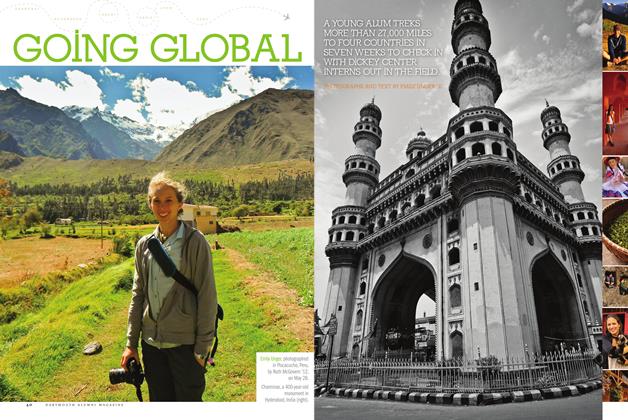

FeatureGoing Global

Nov - Dec By Emily Unger ’11 -

Feature

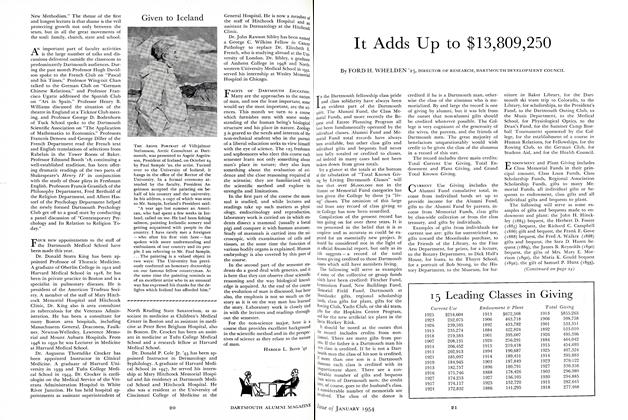

FeatureIt Adds Up to $13,809,250

January 1954 By FORD H. WHELDEN '25