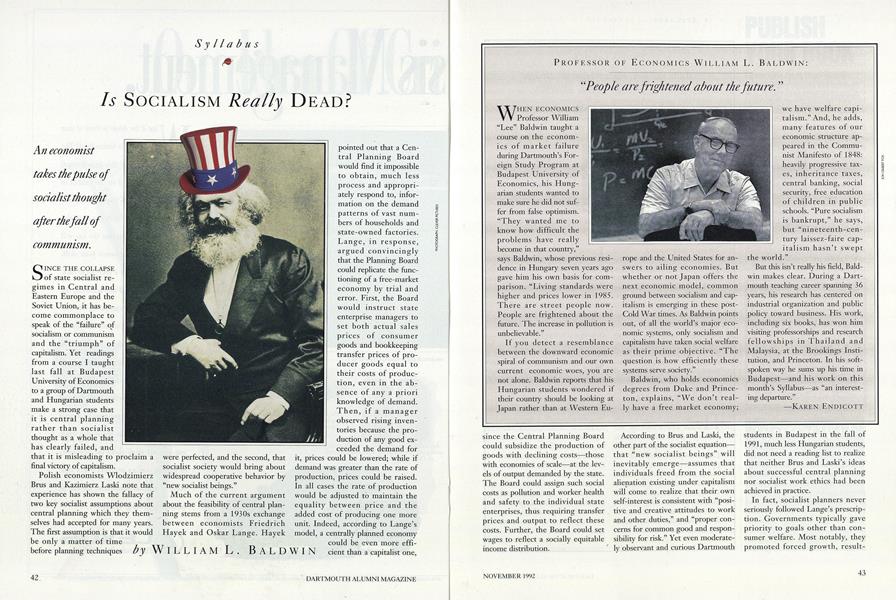

An economist takes the pulse of socialist thought after the fall of communism.

SINCE THE COLLAPSE of state socialist regimes in Central and Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union, it has become commonplace to speak of the "failure" of socialism or communism and the "triumph" of capitalism. Yet readings from a course I taught last fall at Budapest University of Economics to a group of Dartmouth and Hungarian students make a strong case that it is central planning rather than socialist thought as a whole that has clearly failed, and that it is misleading to proclaim a final victory of capitalism.

Polish economists Wlodzimierz Brus and Kazimierz Laski note that experience has shown the fallacy of two key socialist assumptions about central planning which they themselves had accepted for many years. The first assumption is that it would be only a matter of time before planning techniques were perfected, and the second, that socialist society would bring about widespread cooperative behavior by "new socialist beings."

Much of the current argument about the feasibility of central planning stems from a 1930s exchange between economists Friedrich Hayek and Oskar Lange. Hayek pointed out that a Central Planning Board would find it impossible to obtain, much less process and appropriately respond to, information on the demand patterns of vast numbers of households and state-owned factories. Lange, in response, argued convincingly that the Planning Board could replicate the functioning of a free-market economy by trial and error. First, the Board would instruct state enterprise managers to set both actual sales prices of consumer goods and bookkeeping transfer prices of producer goods equal to their costs of production, even in the absence of any a priori knowledge of demand. Then, if a manager observed rising inventories because the production of any good exceeded the demand for it, prices could be lowered; while if demand was greater than the rate of production, prices could be raised. In all cases the rate of production would be adjusted to maintain the equality between price and the added cost of producing one more unit. Indeed, according to Lange's model, a centrally planned economy could be even more efficient than a capitalist one, since the Central Planning Board could subsidize the production of goods with declining costs—those with economies of scale—at the levels of output demanded by the state. The Board could assign such social costs as pollution and worker health and safety to the individual state enterprises, thus requiring transfer prices and output to reflect these costs. Further, the Board could set wages to reflect a socially equitable income distribution.

According to Brus and Laski, the other part of the socialist equation that "new socialist beings" will inevitably emerge—assumes that individuals freed from the social alienation existing under capitalism will come to realize that their own self-interest is consistent with "positive and creative attitudes to work and other duties," and "proper concerns for common good and responsibility for risk." Yet even moderately observant and curious Dartmouth students in Budapest in the fall of 1991, much less Hungarian students, did not need a reading list to realize that neither Brus and Laski's ideas about successful central planning nor socialist work ethics had been achieved in practice.

In fact, socialist planners never seriously followed Lange's prescrip- tion. Governments typically gave priority to goals other than con- sumer welfare. Most notably, they promoted forced growth, result- ing in unwarranted and imbalanced investment at the enterprise level, irreconcilable inconsistencies among various parts of the overall plan, and disregard for the cumulative environmental degradation that has now reached crisis proportions in many areas.

Further, whatever the technical feasibility of implementing Lange's scheme may have been, the incentive structure of a planned economy did not produce the requisite "new socialist beings." Rather, attitudes of managers, planners, and workers alike became epitomized in the oftquoted quip, "under socialism we pretend to work and they pretend to pay us." Enterprise managers saw less career value in maximizing efficiency than in maximizing the size of the enterprise or the number employed, since size enhanced both the apparent importance and responsibility of their positions and the social cost to the state of allowing the enterprise to fail. Planners, in turn, poured new funds into shoring up the weakest and least efficient enterprises, rather than admit to being wrong, about their prospects. Workers in overstaffed enterprises, with no fear of layoffs or plant closings, could see no relationship between their effort and their reward.

Yet even with these shortcomings, central planning was far from an absolute failure. In the post-World War II era, particularly in the earlier years, the socialist nations of Central and Eastern Europe experienced rapid rates of economic growth and industrialization. Standards of living did rise far above pre-war levels. These achievements came at high cost, however, as current consumption was held down to finance what proved to be the inappropriate growth of large-scale basic and heavy industry. Further, bureaucratic conservatism and poor initial investment choices favoring mature industries retarded technological innovation and productivity growth.

The result, of course, is that socialism's postwar economic performance has lagged behind otherwise comparable market-oriented nations—as can be seen in the rates of growth in per capita income and living standards in East versus West Germany, Czechoslovakia versus Austria, Hungary versus Spain, or Bulgaria and Romania versus Greece.

What, then, is left of socialism? Although the term has been widely discredited, debate persists in Hungary and other formerly socialist nations as to the validity of fundamental principles of socialism other than central planning. Brus and Laski, for example, while welcoming the passing of the former repressive, frequently brutal, and increasingly corrupt political order, persist in viewing a socialist economy as ethically superior toalthough less efficient than—a capitalist one. They note, with regret, that in Hungary and neighboring nations such aspects of socialism as low but adequate minimum income levels and old-age pensions for all, plentiful and readily available lowcost housing, assured employment, and free medical care have been lost or harshly attenuated during the transition with no assurance that they will ever be restored.

On the other side of the ethical debate, Hungary's best-known economist, Janos Kornai, defended his strong ethical preference for a free economy grounded in a democratic political system, just as the transition process was beginning in earnest across Central and Eastern Europe. Such a society, Kornai contends, promotes such values as protection of private property, rule of law, individual initiative, entrepreneurship, and fair competition, all of which, he observes, are incompatible with the dulling of personal incentives resulting from socialism.

But is Karl Marx really turning over in his grave yet? In Marx's vision, which American economist Joseph Schumpeter praised as the most compelling in the history of economic thought, nineteenth century-style competitive laissez-faire capitalism—the capitalism Marx observed and analyzed—would inevitably evolve into monopoly capitalism, be wracked with increasingly severe periodic crises along with impoverishment and alienation of the working class, collapse, and be succeeded by socialism. Precisely the reverse form of succession is taking place in the industrialized and midlevel developed countries of Central and Eastern Europe. But Marx, with his prophecy of monopoly, unemployment, and impoverishment in capitalist societies, would surely have recognized and perhaps thought he understood the parallels between his own predictions and painful symptoms of the current transition period—soaring prices in the privatized but often still monopolized sectors, loss of jobs and economic security, and a rise in poverty. Many Central and Eastern Europeans today, imbued since childhood with Marxist thought, may well consider Marx's prophecy vindicated, rather than interpret their suffering as a temporary, factional dislocation.

Ironically, an unwitting menace to that transition may be the Western advisers, both official and selfappointed, who are flocking to Budapest, Prague, and Warsaw with messages of economic salvation through an immediate "cold turkey" plunge into a free-enterprise economy with far fewer economic security programs and public control of the private sector than these advisers have ever known in the modern welfare capitalist systems of their home countries. This danger is particularly acute in light of the perhaps unavoidable political instability sweeping through the formerly socialist nations. No doubt Karl Marx, like the rest of the world, would have been a fascinated onlooker.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryThen lings get ugly

November 1992 By Karen Endicott -

Feature

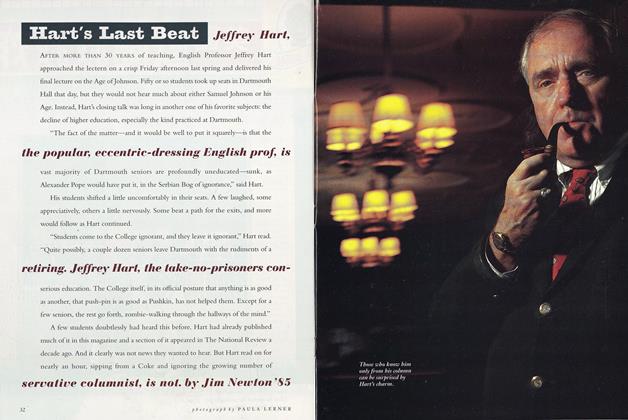

FeatureHart’s Last Beat

November 1992 By Jim Newton ’85 -

Feature

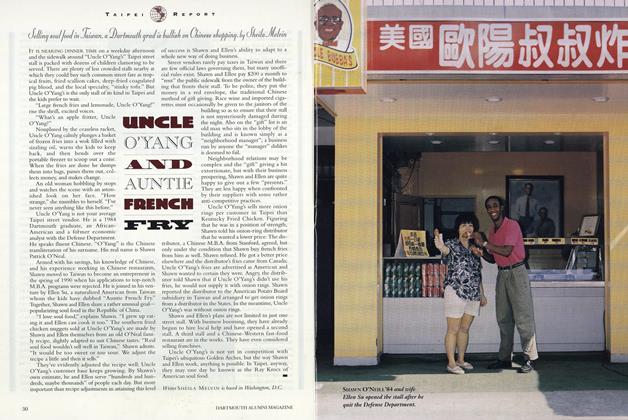

FeatureTaipei Report

November 1992 -

Article

ArticleDr. Wheelock's Journal

November 1992 By “E. Wheelock” -

Article

ArticleLessons of the Law

November 1992 By James O. Freedman -

Class Notes

Class Notes1985

November 1992 By Mark Stern

William L. Baldwin

Article

-

Article

ArticleThe Primary Concern

January 1940 -

Article

ArticleHonored for Service

May 1946 -

Article

Article$12,615

September | October 2013 -

Article

ArticleDARTMOUTH'S FLOOD WORK SALUTED IN SO. CAROLINA

JANUARY, 1928 By "Katherine Dozier -

Article

ArticleJapan

JUNE 1977 By JOSIAH STEVENSON IV '57 -

Article

ArticleCooperative, Not Courageous

January 1941 By The Editor.