IT HAPPENS all the time. Students at a party talk, they connect, it is loud and hot, and they head for the door. They go up to his room... for some quiet, she thinks, and maybe something more. He thinks.. .well, she's in his room.

EARLY ONE MORNING last March a woman student colled thepolice to report that a knife-wielding stranger had broken intoher River Cluster dorm room and sexually assaulted her. Theincident sent shock waves through Dartmouth, jolting the Col-lege's long-felt sense of immunity from big-city problems. Butsomething else stirred in the aftermath of the reported attack.The assault had hit a nerve that was not only painful but pain-fully familiar. Within weeks of the River Cluster attack four otherDartmouth women came forward to claim that they had beenthe victims of .. ~wsexual assault— • stranger rape this time but rape by their classmates, their fellow Dartmouth students, their friends.

As with nationwide statistics on sexual assault, it is hard to tell if the incidence of rape is rising on campus or whether it's only the reports of rape that are increasing. Dean of Students Lee Pelton recently released statistics showing that since 1989 a yearly average of 21.3 sexual assaults or rapes, 4.3 attempted sexual assaults or rapes, and 8.3 cases of unwanted sexual contact have been reported to the College's Sexual Assault and Awareness counselor. Beneath that icebergs tip of reports there appears to be a much larger mass of bad experiences ranging from misunderstandings to out-and-out assault. In a 1986 survey of Dartmouth students Sociology Professor Robert Sokol found that 59 percent of women surveyed said they had experienced male attempts to engage them in sex play (fondling, kissing, petting) or sexual intercourse that they did not want. Sokol also found that 13 percent of men surveyed admitted to having attempted sex play when a woman did not want to, and six percent admitted having succeeded by overwhelming the woman with continual arguments and pressure. Master of Arts and Liberal Studies student Phyllis Riggs surveyed Dartmouth students in 1989 and found that 49 percent of the women said they had experienced unwanted sexual contact (which Riggs defined as kissing, fondling, or touching in a sexual or intimate way short of sexual intercourse) while at the College. Thirty-three percent said men had attempted intercourse with them against their will, while 11.5 percent experienced unwanted completed intercourse (defined as any form of sexual penetration). According to Riggs's survey, nearly all these episodes involved fellow Dartmouth students—not strangers, not people from other colleges—and almost no cases were reported to College officials.

The good news, if you can call it that, is that Dartmouth seems no worse than other colleges nationwide. In 1987 Kent State University psychologist Mary Koss published a survey of 6,159 students at 32 colleges and universities across the nation. They represented Ivy as well as state schools, large and small, urban and rural. She found that 44 percent of women had given in to unwanted sex play, 25 percent of women had been pressured into unwanted sexual intercourse, and nine percent had experienced unwanted sexual intercourse under the threat or use of physical force.

The bad news in Hanover is that some men at Dartmouth are sexually assaulting the women of Dartmouth. What is worse, a surprising portion of Dartmouth men don't seem to find this very disturbing. More than 86.2 percent of the men Riggs surveyed believed that women suffer no consequences from unwanted sexual contact, 84 percent of the men thought that unwanted attempted intercourse leaves no scars, and 44 percent of the men thought that unwanted completed intercourse results in no harm of any kind to the women involved.

But that may be changing. In an ongoing, seemingly spontaneous campus-wide discussion that began last winter term, increasing numbers of students started saying and saying it publicly—that something is wrong between the sexes at Dartmouth. Just as the Anita Hill—Clarence Thomas confrontation awakened national attention to sexual harassment, so the winter and spring term reports of sexual assaults at Dartmouth seem to have prompted students to confront the sexual-assault issue head on. Some 150 students, male as well as female, held two spring-term anti-rape rallies on the Green and in front of Parkhurst and marched to President Freedman's house to present the College Trustees with demands for greater safety, education, and counseling measures and stiffer penalties for assault. Students packed a large lecture hall for debates and talks about Dartmouth's social climate. Four female students got together and, calling themselves the Cassandra Project, performed student-written poetry and vignettes about sexual assault. Two male seniors organized a new group, Greeks Against Rape, as a conduit for educating fraternities and sororities about sexual assault. A group of women formed the Dartmouth Women's Initiative to deal with assault and other issues affecting women. Still other students birthed a new publication, Spare Rib, to examine gender issues on campus. Even for those students who never went near a rally or attended a meeting of Greeks against Rape or read Spare Rib, the issue of sexual assault was unavoidable. All they had to do was glance at headlines in The D to see that other students, both male and female, were keeping up a running commentary of opinion pieces, letters to the editor, and news stories on the topic. Then, too, as fate would have it, the College's Sexual Assault Awareness Week, which had been over a year in the planning, occurred right in the middle of spring term.

With growing momentum, sexual assault is moving out of secrecy and female silence and into the public eye. "I think more women are finding the courage to come forward,'' says Mary Childers, director of the Women's Resource Center. According to Dean of Students Lee Pelton, "We may be witnessing at Dartmouth a moment of empowerment for women. Women are saying we're at a point where we wish to claim our rightful position in this place we call Dartmouth." At a Dartmouth "town meeting" he convened in early April to discuss assault and related issues, Pelton put men squarely into the picture with a point-blank statement: "Rape will only stop when men stop doing it. This is a male social disease and men must take responsibility."

Not surprisingly, male reaction has been varied. Some men donned pins that proclaimed "Another Dartmouth man against rape." Members of Alpha Chi fraternity joined women in a Take Back the Night march down Webster Avenue. But, as Dave Murphy '9l wrote in Spare Rib, "Many men on campus claim that they are put on the defensive by the issues of sexual assault because they feel personally accused, as a man, whenever the topic is discussed." For his part, Dean Pelton thinks defensiveness is healthy. Only after seeing what people are defensive about, he says, can they move on to understanding why they feel that way. For members of Sigma Nu fraternity, however, there was no doubt about why they were feeling angry about the sexualassault issue. Brothers report having been derided as rapists when another brother suspended by the College for alleged sexual misconduct continued to live at the fraternity. At the time the house, next-door-neighbor to the president's residence, was independent of the College; officially, the student was off campus. When women students distributed posters warning other women of the suspended student's presence I on campus and outrightly calling him a rapist—many men were outraged. Similarly, posters that declared "Frats Rape" further polarized both sides of the issue. Yet, whether their reactions were defensive, angry, or empathic, "more people are putting themselves in the spectrum," said history and studio-art major David Yocum '92 last spring. He added: "Over the last two months the definition of what is mainstream is changing. The issue is more topical and more voices are being heard."

What is it that people see as they take this look in the institutional mirror? Although 45 percent of the students at Dartmouth are women, many of them say the place hasn't fully accommodated them yet—even after more than two decades of coeducation. Gone are the days of overt sexism with catcalls and whistles, protests against coeducation, and songs about "cohogs." Gone is the time when men spotlighted and screamed ratings at women as they walked into Thayer. But according to Marga Rahmann '77, who as associate director of the Hopkins Center has observed the campus and worked closely with students over several years, now such things happen behind closed doors rather than on public display. And, she says, "Women on campus fear violence." (A '94 fraternity member disputes this perception, saying that he has never heard women on campus actually state "I fear violence." But he nonetheless says that "most of them are cautious.") The fear—whether expressed verbally or behaviorally—is a disturbing continuum between past and present. There may be plenty of male bravado in such Dartmouth rallying calls as the old "Lock up your daughters, Dartmouth is in town again" or the 1960s banner "When better women are made, Dartmouth men will make them," or the still current "Cold Weather, Cold Beer, Cold Women," or the latest in the long line of such remarks: a 1991 fraternity beach party invitation reading "All whales will be harpooned." To a number of women, however, these cries and slogans are not just insulting, they are menacing. Some women cope by pretending that nothing is meant by the remarks. Spare Rib quoted an overheard comment by a woman student in Collis last winter: "Men make sexist jokes in front of me all the time, but I think I'm secure enough as a woman to ignore it instead of becoming offended." Maria Parks '94 says that when she lets men know that she is offended by their references to "chicks," "babes," and "skirts," their response is usually a patronizing "Take it easy. Calm down." In an opinion piece in The D spring term Julie Kenerson '92 publicly rejected the idea that it's the women who can't take a joke. "Some men argue that this [namecalling] is harmless, it doesn't really mean anything when men talk about women in this manner," she wrote. "An attitude that accepts—if not encourages sexual assault begins with things as simple as terminology. Men don't think that calling women 'chicks' or 'cracks' is a big deal; they don't think that it is a big deal that they feel women up. But it is."

Indeed, a number of women have told this magazine that the line between verbal and physical harassment is too often crossed and that women need to be warned of the dangers that await them. Thanalakshmi Subramaniam '92 recalls routinely having to pass fraternity row when she lived in the Choates. "You never know when drunken men will be verbally and sexually harassing," she says. She talks, too, of "friends who have gone to fraternity basements and within minutes are felt up by men they don't even know. Outside of fraternity basements they say they are nice men who wouldn't harm women." Nicole Clausing '92 says people avoid certain fraternities because they know friends who were raped there. According to Maria Parks, undergraduate advisors routinely advise women to steer clear of such fraternities. Students say first-year women are particularly vulnerable to harassment and unwanted sexual advances because as newcomers to the campus they are unsure of the unwritten social codes. Yet, even after freshmen year, points out Subramaniam, women—and men—labor under what she calls Dartmouth's rape myths: If I don't go into certain fraternities I'll be OK. These things happen to other people. He's a Dartmouth boy, so he wouldn't do it. He's an athlete, so he wouldn't do it. He's an all-American boy, so he wouldn't do it. He's in a good fraternity, so he wouldn't do it. If she's in a fraternity basement she's asking for it. If she's drunk she's asking for it. "No" means "Yes."

Dartmouth students are so special that they don't need to examine their own behavior.

The bottom line here is that men and women seem to have very different ideas about the rules of social interactions, the meaning of behaviors, and even the meaning of words. Adding to the confusion of conflicting attitudes and messages is the fact that some women do go to parties to "scam," to have an encounter of the sexual kind. Then, too, men say that some women give mixed messages: that women may say "no" but their body language may mean "yes." Increasingly, however, women are telling men that the "no means yes" scenario is rarely if ever more than male fantasy. "So you mean if a woman says no, I should stop?" one man asked after a Cassandra Project performance about sexual assault. The question revealed how far apart men and women often are in reading situations. But just as the radical feminist claim that all men are rapists is defiant and offensive shorthand for saying that a woman can never be sure who

among men will be a rapist, experts on sexual assault say that it is misguided in this post-sexual revolution age for men to assume that each woman who enters a fraternity basement or a bedroom is saying yes to sex—especially when the woman is saying no. "Don't rely on your ability to interpret non-verbal signals," is Mary Childers's advice to students.

It sounds simple enough: When in doubt, talk it out. And yet, speak to students on campus and what you'll hear is that, on the individual level, men and women don't do a whole lot of communicating about sex—or anything else. Angela Fung '92 will tell you about a friend of hers who was amazed that Fung and her boyfriend keep each other posted about their schedules, about such matters as what evenings they can or cannot have dinner together. If students have trouble communicating about such mundane topics, it is not surprising that, as Greeks against Rape cofounder Joshua Stein '92 reports, "There's usually not a lot of talking about sex." Instead there seems to be a general assumption among students that everyone is freely and fully sexually active. Various students report that young people feel pressure as early as their mid-teen years to participate in sex, a fact borne out by national surveys on adolescent sexuality. Although the threat of AIDS would seem to encourage people to know their partners well before jumping into sex, many students appear to engage in what psychiatrist Harry Beskind, an adjunct professor at the Dartmouth Medical School, calls a "genital handshake." It may be a onenight stand or the beginning of what passes for a relationship at Dartmouth. Greeks against Rape co-founder John Kim '92 describes a typical scenario: "You're in a frat basement, you have a few beers, a woman enters and you talk to her, you go to his or her room, have sex or go pretty far, and that's the beginning of a relationship." Heather McDaniel '92 explains in Spare Rib, "Generally, a relationship here lasts about three weeks: the first week with the man really into you, the middle week where you're kind of getting into him, and the last week where you're really into him and suddenly something goes wrong and then it's over with." Angela Fung reports: "There's a lot of casual sex or else it's like you're married. There's not much in between. People don't want to be seen holding hands or engaged in public displays of affection." Indeed, "Relationships are a big deal here," David Yocum. "People have sex to make believe they're having a relationship... There's a lot of intimacy before there's friendship." Psychiatrist Beskind puts a different interpretation on that scene: "They may be naked, but that's not intimacy."

Student cynicism about relationships reflects the obstacles in the way of longterm friendships during the Dartmouth years. The four-term Dartmouth Plan can prove especially disruptive, according to students. They may meet each other one term only to face upcoming separations that can last the next two and a half years. Steve Lough '87, back on campus for reunion last spring, reflects that it is unrealistic to think that college relationships will last because people expect that their future careers will drive them apart. Moreover, with an increasingly diverse student body, he says, there is less chance of finding people with the common interests that cement longterm relationships. Then there's the pressure at least some fraternities exert on men to choose "brothers over babes." As Matt Wilson '92 explains in Spare Rib, "I've felt the pressure to get out, because when I'm in a relationship I spend more time away from the house and I don't see my friends as much."

What does all this have to do with sexual assault?

It's one thing when these relationships or nonrelationships happen between consenting partners. But when one partner does not consent or is not capable of consent, it is quite another thing, according to lawyers: it is assault. Given that the social scene at Dartmouth revolves around fraternity parties where alcohol flows freely, it is easy to see how consent becomes an issue. "In nine out of ten cases of alleged sexual assault at least one person has been drinking," reports Mary Childers. Plying a woman with alcohol is a famous way of "getting a yes out," as University of Pennsylvania anthropologist Peggy Reeves Sanday discusses in Fraternity Gang Rape, a chilling examination of life at an unnamed university. Alcohol not only interferes with informed consent, it also makes it easy for people to deny that they may have coerced someone into unwanted sexual activity. Combine inebriation with what John Kim describes as extreme pressure to have sex and you have a recipe for assault. "If you leave a party together you're expected to have sex," Kim says. "Then people ask you about it and if you say no their answer is 'oh, that's too bad.'" Childers reports that students don't seem to realize that they don't have to act on every sexual impulse. "Ours is an increasingly sexualized culture," she says, explaining that "some people feel entitled to sex" and, even more disturbing, "some men are not trained to hear 'no.'"

Kim describes how men are socialized into this feeling of entitlement, adding that he feels he is an exception. "If you want to be cool you have to be manly, forceful, aggressive. Look at the 'successful' men: Donald Trump, Lee lacocca, Ross Perot. They don't take crap from anyone. Of course if a woman acts like this she's called a bitch, like Leona Helmsley and Ivana Trump." Under the influence of alcohol this attitude "sets up the perfect scenario for a rape to occur and the woman won't even realize it's rape, even though she will feel terrible and violated," says Kim.

No one knows precisely how often Dartmouth women fail to recognize sexual assault because of being drunkor, for that matter, being in a state of denial or ignorance. Liane Bromer '91 recalls that it wasn't until the College's sexual-assault counselor, Heather Earle, conducted a training session for undergraduate advisors on handling assault that she recognized her own experience of assault tor what it was and could finally make sense of the emotional turmoil she had been suffering. "I had all the symptoms assault victims suffer: depression, introversion, self-hatred, blame, crying and not knowing why," says Bromer. Part of the problem, she says, is that "for men and women there are different meanings of sex. Men see it as casual. Women are not supposed to have sexuality or have sexual needs. They're supposed to cater to the sexual needs of men. Some men push and plead and don't get it that no means no."

Men, too, may not be aware that they are engaging in sexual assault. "Everyone will say they're against rape, but when they act without thinking, it may be in ways that are rape and they don't realize it. They may be thinking of rape as a guy with a gun forces himself on a woman," explains John Kim. Agrees Joshua Stein, "In many cases men don't even know they're assaulting women." Then, too, "It's so easy for people to explain away issues they don't want to deal with by blaming problems on drunken behavior," says Thanalakshmi Subramanian.

Prompted by growing student consternation about sexual assault—and students' increasingly forthright discussions of behaviors and attitudes on campus the College is making it easier than ever for men and women to know what sexual assault is, how often it happens, and what the consequences are. On order of Dean Pelton, sexual-assault statistics and sanctions are now posted each term, without names or other identifying information. The College has revised yet again its Student Handbook information on what constitutes sexual misconduct. No matter how clearly the College states its positions, however, questions of interpretation will inevitably arise. When it is one persons word against another's, "there are a lot of gray areas," explains Mary Childers. Nonetheless the College's regulations are consistent with Dean Pelton's assertion that rape will only stop when individuals take personal responsibility rather than casting blame on drinking, on peer pressure, on fraternities.

Fraternities. A small but growing minority of women and men on campus have argued for some time now that the houseswhich continue to be the heart of Dartmouth social life—play a major role in making Dartmouth "rape-prone" by creating an atmosphere that condones sexual harassment and assault. The fraternity question surfaced early in spring term when a rally held in front of Parkhurst called for the abolition of fraternities. Trustees Chairman Ira Michael Heyman '51 assured rally participants, "The Trustees recognize that sexual assault is a serious matter which requires the full attention of the College." But Dean Pelton let it be known that the fraternity issue must be dealt with by the entire Dartmouth community, not just the administration.

Within the community, opinion is generally divided between those who think that the structure of fraternities encourages sexism and misogyny and those who think these attitudes exist and always will exist in the larger society, whether or not there are fraternities. Students passionately debated the issue throughout spring term, in specially scheduled sessions, in The Dartmouth, and in small groups. "This was the issue people talked about over lunch," David Yocum noted last spring. Part of the debate centered on an extensive Women's Studies paper Scott Straus '92 wrote analyzing sexist, misogynistic, and homophobic elements of pledge rituals. He stated his views in a formal on-campus debate and published a condensed version of his paper in the selfproclaimedly progressive student newspaper The Bug. Explaining that pledges are called wimps, faggots, and a variety of names referring to female genitalia, Straus argues that initiations and fraternity culture desensitize men to sexual assault and rape and institutionally sanction men to be abusive. He contends that "Pledges who find themselves disempowered and labeled 'feminine' must, in order to prove their fraternal worthiness, demonstrate their (hyper) masculinity in terms of heterosexual conquest, alcohol consumption, and disinterest in or animosity toward women." Greeks against Rape co-founder Joshua Stein calls Straus's arguments "far-fetched," yet readily states that there are abuses within the fraternity system that should be rectified. "Misogyny, sexism, racism, alcohol abuse, anti-intellectualism, and homophobia can be found throughout our society," fraternity member Alexander Kaplan '93 wrote in an opinion piece in The Dartmouth. "If the system were abolished, these problems would still exist at Dartmouth. The friendship and camaraderie, though, may be harder to come by."

Both sides agree, however, that much of Dartmouth's social scene takes place on allmale turf. According to critics of the Greek system, this puts women—and unaffiliated men—at a serious disadvantage. The fraternities can call the shots, from who gets served beer to what it means for a woman to be in a certain area. The members make the rules and don't have to inform anyone else. The resulting inequalities of power appear to be far-reaching; Jud Dean '92, who chose not to rush, estimates that 95 percent of the campus is affected by the Greek system. Women who say they feel intimidated at fraternity parties often go anyway. "Dartmouth has a reputation as a party school, so women assume as freshmen that that's what you're expected to do," Nicole Clausing told this magazine before graduation. "But people get disillusioned. The younger women are the ones who stay. I know I'm not there." John Dean '92 explains that first-year students are indeed the most vulnerable: "They don't know how to act, what their rights are. A girl in a basement doesn't know how to stand up to upperclassmen and is afraid of being known as a 'cold bitch' if she refuses." John Kim describes going to a sorority party and for the first time understanding the alienation many women—and non-affiliated men—experience at fraternity parties. "I felt like a real non-member," Kim says. "It's reassuring for me to have brothers present. I could understand what it must feel like to have large numbers of males around, to feel threatened."

Greeks and unaffiliateds alike agree that there is room for social change at Dartmouth, although their scenarios vary. "Even people in the system feel constrained and wish there was an alternative. I don't want to spend all my time in a fiat basement. There are more sides to my personality than that," explains Joshua Stein. He, like others, would like to see more College-sponsored social events, such as Casino Nights and dances. Some students—most notably Student Assembly President Andrew Beebe '93—have been calling for all houses to go coed or for the Greek system to metamorphose into coed social clubs which all students could join at will without any kind of rush. Kathleen Merrill '92 has suggested more affinity housing based on common interests in such areas as the arts or literature. The goal of such changes would be to provide "another way to meet people without elitism," says Liane Bromer. Even one of the harshest critics of the Greek system, Thanalakshmi Subramaniam, maintains that "By abolishing the Greek system we don't mean taking a blowtorch to Webster Avenue. We mean getting rid of the abuse."

Of course, most changes do not happen overnight. Some campus observers wonder whether the fracas over sexual assault will have graduated with the seniors who spoke out the most loudly about the issue. Over the summer some fraternity members told this magazine that they think sexual assault was the issue of the moment, and that the moment is past. That may turn out to be just wishful thinking. Already there are signs that student groups and College administrators will be keeping up a determined effort not only to keep the issue alive but to work out solutions as well. For example, faculty and student advisors are being trained to give personal support and guidance to students who bring charges or find themselves accused of sexual misconduct; some 200 students, male and female, turned out for the program, according to Mary Childers. Students, including members of a Student Assembly Task Force on Sexual Assault that was launched last spring, are working with administrators on ways to better educate first-year students about sexual assault without unduly frightening the women or alienating the men. Freshman trip leaders and undergraduate advisors are being more fully trained about communications between women and men. Members of the College's five-year-old Older and Wiser program, which links senior and first-year women, say they will be more explicit about sexual abuse in future. There is talk of creating an Older and Wiser organization for male students. Translating his conviction that men must provide education and role models for other men, Dean Pelton has been meeting with male faculty, coaches, and administrators to discuss sexual assault and other social issues. The Dartmouth Women's Initiative worked throughout the summer to plan activities that would keep sexual assault at the forefront of student awareness on into the year. Greeks against Rape similarly sponsored meetings over the summer and plans to keep going as a primary means of spreading the message about how to prevent sexual assault. "I wish that everyone here would turn the amazing powers of analysis they have for academic issues to personal issues," Angela Fung said last spring before graduation. That seems to actually be happening. Even so, there's no guarantee that sexual assault will ever be a thing of the past. But as Mary Childers says, "There are students who are eager to keep this from happening to another class of women."

In a 1989 survey byPhyllis Riggs, 4-9 percent of women saidthey had experienced"unwanted contact."

"This is a malesocial diseaseand men must takeresponsibility."Dean Lee Pellon

"The younger womenare the ones who stayat parties. I knowI'm not there."Nicole Clausing '92

Since the late eightiesstudents have heldmarches against rape.

"If you leavea party togetheryou're expectedto have sex."John Kim '92

"For men and women there are different meanings of sex. Men see it as casual."Liane Bromer '91

The DartmouthAnimal's symbolic deathwas sculpted in '69.

Nearlyall theseepisodesinvolvedfellowDartmouthstudents, andalmost nocases werereported toofficials.

winter, students startedsaying thatsomethingis wrongbetween thesexes atDartmouth.

Men and womenseem to havevery differentideas aboutthe rules ofsocial interaction, eventhe meaningsof words.

Manystudentsappearto engagein whatMed SchoolpsychiatristHarryBeskind callsa "genitalhandshake."

Menmay not beaware thatthey arecommittingsexualassault.

sides agreethat much ofDartmouth'ssocial scenetakes placeon allmale turf.

Someobserverswonderwhether thefracas oversexualassault willhave graduated withthe seniors.

KAREN ENDICOTT is this magazine's faculty editor.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

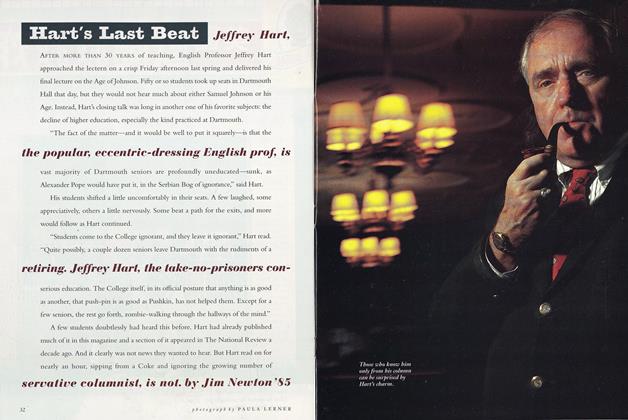

FeatureHart’s Last Beat

November 1992 By Jim Newton ’85 -

Feature

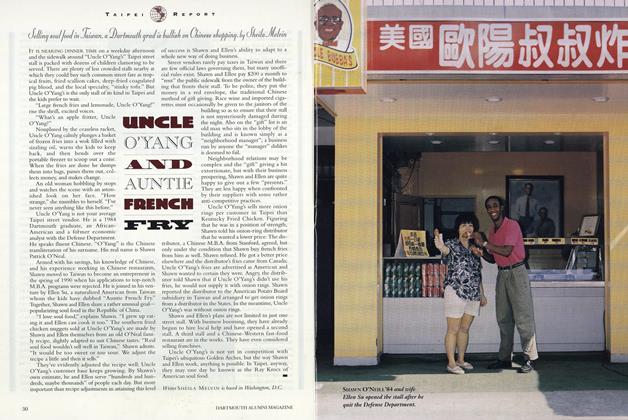

FeatureTaipei Report

November 1992 -

Article

ArticleIs Socialism Really Dead?

November 1992 By William L. Baldwin -

Article

ArticleDr. Wheelock's Journal

November 1992 By “E. Wheelock” -

Article

ArticleLessons of the Law

November 1992 By James O. Freedman -

Class Notes

Class Notes1985

November 1992 By Mark Stern

Karen Endicott

-

Article

ArticlePASS THE ICED NIETZSCHE

September 1993 By Karen Endicott -

Article

ArticleThe Daughters of Eve

October 1993 By Karen Endicott -

Article

ArticleDaedalus with a Power Glove

OCTOBER 1994 By Karen Endicott -

CLASSROOM

CLASSROOMPreparing for a Life in the Pits

Nov/Dec 2000 By Karen Endicott -

Article

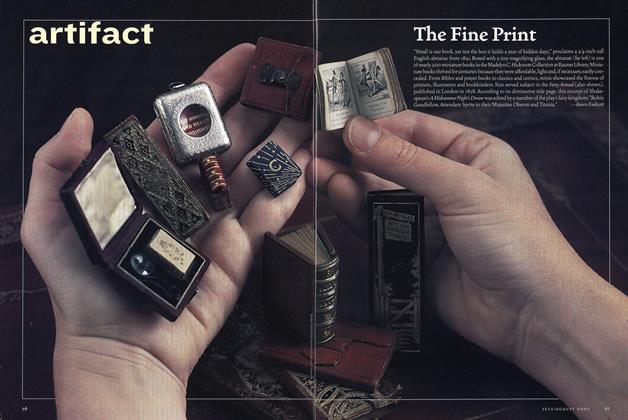

ArticleThe Fine Print

July/Aug 2002 By Karen Endicott -

Classroom

ClassroomThe Art and Science of Group Dynamics

Nov/Dec 2002 By Karen Endicott

Features

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryDartmouth’s Unknown History

JANUARY 2000 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryBAKER TOWER WEATHERVANE

MARCH | APRIL 2014 -

Cover Story

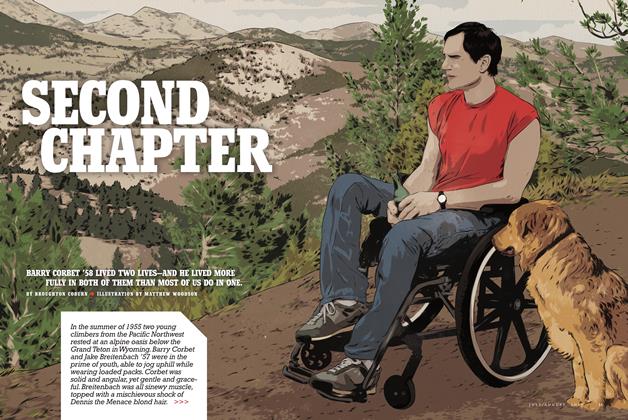

Cover StorySECOND CHAPTER

July/Aug 2013 By BROUGHTON COBURN -

Feature

FeatureA Course of Reading for Dartmouth Men

December 1955 By CHARLES C. MERRILL '94 -

Feature

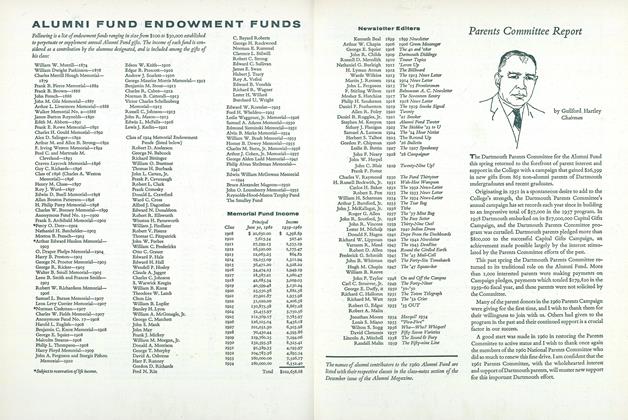

FeatureParents Committee Report

December 1960 By Guilford. Hartley -

Feature

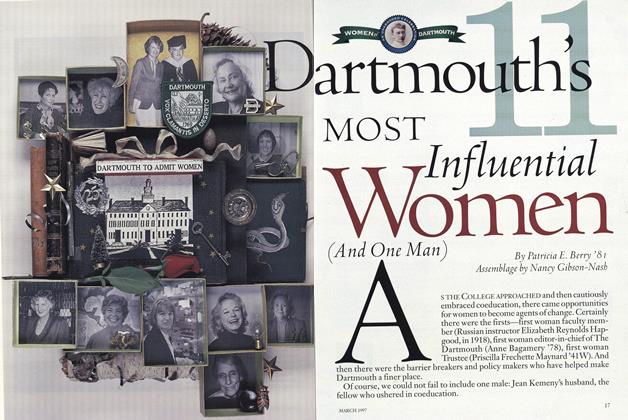

FeatureDartmouth's Most Influential Women Influential Women

MARCH 1997 By Patricia E. Berry '81