To get the other Ivy schools to reinstate their banished geography departments, what we need is a good war.

ONE OF THE GREATEST CURSES and pleasures of my life is being a geographer. The curse: Do you have any idea how many times I am asked to name the capital of Kentucky (I don't even care) or how many people pick me as their partner in Trivial Pursuit or Jeopardy?

The pleasure: Practicing real geography, using and teaching geographical skills to solve real problems, and understanding the world around me. More of this later.

It always amazes me how a discipline as old and distinguished as geography came to be so misunderstood through the centuries. Granted, there are some who have not succumbed to the terrible simplification of geography which has reduced it to a boring recitation of names of places and products and lists of the longest, biggest, highest, ad nauseam.

Geography's beginnings are truly ancient and venerable, dating probably to the earliest member of the species Homo erectus, who was concerned with getting back to the home cave from a hunting trip or determining from which direction the wind usually blew in order to build the family shelter more effectively. The first acknowledged geographer was the Greek scholar Thales (624-547 B.C.), followed by his student Anaximander (610-546 B.C.). They were occupied with weighty questions about the where of things and why they were there, and whether the changes within those places were predictable.

Geography literally means "earth description." To elaborate a bit, it is the description and explanation of where things are on earth and why—the why of where. The early geographers were concerned with how the earth was shaped and how to determine where they were on it. They were also interested in earth's location in relation to the other chunks of matter orbiting in space and, consequently, they became excellent measurers, geometers, and were generally very numerate. They measured and mapped the earth and the heavens and, when they found places that were missing, they explored, calculated, and worried. In exploring, they added unknown places to the maps but, more important, they brought these unknown places into the known system of places. They kept making new maps because places were added to the maps and the places they mapped became more closely connected to each other as the world used their maps. Thus, the places and the things in them continually changed and kept on changing—even their names. Geography and maps were in constant motion, which is why, to this day, memorizing places and their names (remember Leningrad) and the things in them is not a very clever thing to do.

There are a number of generalizations derivable from the foregoing. Clearly, geography is an old art and in its evolution it has spawned many new disciplines—geodetic science, cartography, geomorphology, to name a few. Second, and even more important, genuine geography is the art and science of place (or location, if you prefer), which raises the questions: where is it, why is it there, and why and how does it change?

Given this rapid explanation of geography's origins and meaning, why would we ask, "What is the capital of Ohio?" Ohio's capital, incidentally, has changed at least three times because the geography of Ohio has changed. Why would we ask, "Where is Yugoslavia?" Would you ask a mathematician for the square or cube root of 127.721? The mindless memorization of places and place names, like memorizing square roots or memorizing events for every year of the nineteenth century, is silly and useless unless there is some relevant question or problem associated with the places, the year, or a number. Geographers in the nineteenth century were not so much interested in the city that produced the most silk hats. They were more interested that the invention of the silk hat led to the formation of many small lakes and bogs in the United States, because there was now a reduced demand for beaver furs and the reprieved beavers set about their normal business of reshaping geography. Instead of asking what is the capital of Japan or united Germany, modern geographers find much more exciting the question: "How closely connected are these two capitals and how can we measure the degree of connectivity between these two places?" You can measure connectivity with such data as finding the number of minutes of international telecommunication traffic (MiTTs,) or measuring the amount of foreign direct investment between these places, or any other number of flows across space connecting these places. Places and the flows between them are the significant geographical issues which allow us to determine how and why places change, how intensely places interact, whether the connections between them are becoming stronger or weaker, whether the flows are one-sided or equitable or....

To repeat: geography is the art and science of place, but its value can only be appreciated if the questions posed about places and location are important and if they are geographic questions. During my tenure as Geographer of the United States, my staff's geographic analysts addressed a long list of questions relevant to U.S. foreign policy. Some of the analyses we provided to the Secretary of State included the following:

Where was the United States vulnerable to terrorist. Where was the United States vulnerable to terrorist attacks (based on mapping such attacks over time), and where were future attacks most probable?

Was there a geographical pattern to the spread of AIDS, and, if so, did the disease diffuse in ways that affected the United States? (The answer was yes; the primary danger was a Third World heterosexual pattern of diffusion to which the country was vulnerable on its southern flank. The U.S. policy of repatriating Haitians may well be driven by this geographical issue.)

" Do there exist geographies of refugees, of hunger, of piracy? With appropriate spatial analysis, is it possible to predict their future spatial patterns and changes?

A myriad of similar significant questions were posed and analyzed geographically—questions about the origin, processing point, and flow of cocaine; places of water shortage, and potential conflict; the geography of famines; and more.

Any cursory examination of the globe readily reveals that the world, at all scales, is divided, demarcated, separated in some form or another into distinct places by boundaries. The places take the form of neighborhoods, towns, counties, provinces, states, corn belts, countries, the Middle East, and on and on.

These separating lines, in fact, border on (pun intended) evil, given the hostility they create and the damage they frequently cause. Such boundaries include most of the international political boundaries around the world, past and present.

For example, the Great Wall of China, an enormous engineering feat that cost thousands upon thousands of human lives and countless pain, was a total failure. Its only effectual function has been its recent attractiveness to foreign tourists and their money. Similarly, Hadrian's Wall, the Berlin Wall, and the Iron Curtain were negative, destructive, and, basically, failures. The U.S.-Mexican boundary represents an excellent example of a miserable and ineffective barrier. American threats to build walls and moats and fly dirigibles over the boundary are as silly as the Great Wall of China. As long as the "joining plane" between Mexico and the United States is conceptualized as a "separating plane," as geographers put it, there will be no permanent solution to the problem of Mexican illegal immigration. The solution lies not in the strengthening of the boundary but rather in a joint solution to the Mexican economic problems that generate the migrants. In the long run, such a solution may even be cheaper, less tension-producing, and surely more permanent than bigger and better fences.

Since the 1950s the practice of drawing boundaries has spread in earnest to the seas and the earth's oceans. The water bodies have been crisscrossed with territorial sea boundaries and exclusive economic zones as well as claims, counterclaims, and disputes over islands, straits, and what areas belong to whom, all of which give many geographers steady employment. The maritime delimiting process has also created strife: Colonel Kaddaffi's "line of death" in the Gulf of Sidra; the U.S.-Soviet (now Russian) dispute over their maritime boundary in the Bering Sea; armed conflict over the Spratly Islands by China and Vietnam with Malaysia, Philippines, and Brunei watching with claim slips in hand; and literally hundreds of other maritime boundary and island disputes around the world.

To be fair, however, some countries have recently begun to rethink boundaries and disaggregate some of the functions of a boundary. Boundaries may be viewed as having layers of functions—customs, immigration, trade and tariff, military. The European Economic Community has been going though a process of joining its boundaries in terms of some functions—tariffs, labor movements, and so on. Each country will still maintain many of its own boundary functions—immigration laws, political sovereignty, and the like. Indeed, the trend to separate boundaries into functional layers or subsets is a positive one but results in newly bounded places—in the case of Western Europe, the E.C.—and retains many of the separations between members while creating a new economic boundary with the rest of the world.

In contrast, the collapse of the Cold War and the machinations over a prospective new world order has sparked the sovereignty aspirations of ethnic groups and nations; the result has been a surge of splintering movements breaking up currently existing states. From Slovakia to Slovenia, from Tartarstan to Ossetia, and from Quebec to the Kurdish areas, clamors over new and old boundaries are being made to delimit new places.

The real solution for the problem of bounded space with barriers of various kinds, however, is complex. What must precede a solution is a psychological change in the way boundaries are perceived and understood. The zones where countries meet should be viewed as joining places, zones of opportunity and cooperation, places where states and people may come together. They must be viewed as even more than mending walls, as places where differences can be diminished and interaction encouraged and applauded! The great poet Robert Frost wrote in amazement about the common perception of boundaries as separators:

There where it is we do not needthe wall:

He is all pine and I am appleorchard.

My apple trees will never get acrossAnd eat the cones under his pines, I tell him.He only says, 'Good fences make good neighbors.'Spring is the mischief in me, and I wonderIf I could put a notion in his head:'Why do they make good neighbors?

Before I built a wall I'd ask to knowWhat I was walling in or walling out,And to whom I was like to give offense.Something there is that doesn't love a wall,that wants it down.'

PERHAPS IN TIME WE WILL REALIZE that walls and fences, like all human-created devices, require rethinking and new forms. Perhaps someday we all will look at boundaries as zones that bring places and peoples together to share ideas and cultures and goods. Perhaps someday spring will be the mischief in us all!

As Frost showed, one can apply geographical knowledge to very personal and local questions. For example, buying a home can be done with geographical intelligence or indifference. A local realtor will usually tell a client that the three crucial factors in selecting a home are "location, location, location!" Perhaps, but commissions certainly matter and the preferred location, from the point of view of the realtor, is her own sales territory. Buying a home requires spatial (real, geographic) information. After selecting the general region in which you must find a home, you should have or acquire information about the crime rates by neighborhood—for instance, the drainage and flood areas, and the radon emission rates by area. When the important and frequent destinations for the family are known—such as office and school—information on the road system and public transport is necessary. Very important from an economic point of view are data on housing costs and, especially, appreciation rates by neighborhood. Knowing which areas have peaked in value or are on the way up can result in a brilliant investment. Most of these data can be gathered from local officials such as the police station or the local newspaper. The information may not be readily available, but it can be collected and used and the more we demand such geographical information the sooner it will be readily available and we will be properly geographically informed.

Let's now change our scale and examine a set of geographical questions at the international level. The collapse of the Soviet Union and the end of the Cold War have led to the remarkable creation of new geographies for the newly created countries which were once republics of the USSR. The old Soviet Union, and the Russian Empire which preceded it, were, in fact, a collection of disparate places (e.g., Estonia, Georgia, Uzbekistan), most of which had been at some earlier time kingdoms or emirates or some other type of independent entity. At some point these places were forced into a foreign state, Russia or the USSR, and their geographies—that is, their connections with other places—radically changed. For each of these places, new connections were created with Moscow and the many places contained within the Soviet Union's international boundary. All new flows moved over these new connections, including the migrations of Russians, the flows of Communist Party authority, new economic flows, all of which radically altered these newly incorporated places. New "Soviet" geographies were created.

Since the collapse of the old Soviet Union, the former republics and even places within Russia and within some of the other republics have been rapidly breaking or at least loosening their connections to Moscow and the old Soviet system of places. They are all rapidly establishing new connections with new places beyond the old Soviet international boundary. The new Baltic states, Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania, have turned their countries westward and are reconnecting with former places of contact. Trade, aid, culture, and all other flows are being created with western European countries and North America. The former Central Asian republics—Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Turmenistan, Uzbekistan, and Tadjikistan—are radically creating new internal and external "geographies." They are receiving many hours of television programming each day from Turkey, copies of the Koran from Saudi Arabia, imams from Iran, and aid from all of these new connections as well as from Pakistan. Trade and investment flows have been stimulated by entrepreneurs from the West, Korea, Japan, and many other parts of the world. Yes, these former Soviet places are changing the names of their countries, capitals, and other cities; in most cases they are bringing back the former names, but the important geographic changes are in the new connections and the new flows to these renamed places. Knowing how and where these new connections are being established is critical geographical information for businesses, intelligence services, and diplomats around the globe. Good geographical analysis can provide insights, understanding, and even some prediction regarding the creation of these "new geographies."

The training of geographers is thus crucial to a country's management. As an academic discipline in America, geography dates from the late nineteenth century. The first geography courses in America were probably taught by scholars at Dartmouth, Princeton, Yale, and Columbia. The emphasis then was mainly on physical geography, but, by World War I, geographers increasingly studied socioeconomic phenomena and, especially, politics, which gave rise to the first studies in geopolitics. One of President Woodrow Wilson's close advisors in the postwar peace negotiations was a noted geographer, Isaiah Bowman. He later became the president of Johns Hopkins University, where a fine department of geography still prospers.

There is an old saw in our discipline—war is good for geography—which can be readily verified. Both World Wars led to the amassing of geographers in great numbers in the government to provide advice and counsel. Serenity seems to lull governments and universities and lead them to devalue geography and reduce the number of practitioners and departments. Relative peace and economic constraints led to the closing of many geography departments in the United States during the seventies and eighties. Geography departments were vulnerable. They were small and had few defenders in the increasingly competitive academic environment where new and sexy fields were emerging—environmental science, AfricanAmerican studies, etc.

Here at Dartmouth, wisdom and intellectual honesty have prevailed and geography has been an important part of the curriculum for more than 220 years. Ours is the only department in the Ivy League (although most other Ivy schools have geographers on their faculty), and we can boast of being one of the best in the country The geography faculty at Dartmouth includes remarkable people such as Bob Huke '48, who has taught Dartmouth students for more than 30 years and is one of the world's experts on agricultural geography and rice. Research by department faculty ranges from analyses of the regional need for emergency services to the geographical distribution of acid rain in New England to the spatial diffusion of AIDS. The department has also recently developed a new high-tech mapping and spatial-dataanalysisllatheb—the Rahr Lab, named for Guido Rahr '51, who has provided support to the department.

Yes, geographers still make maps. Computer cartography and complex geographical information systems (GISs) allow analysts to create layer upon layer of spatial information, from topography to land-use to population density. GISs not only display information but also predict impacts of proposed projects or developments. In essence, geographers can produce predictive spatial models of communities, counties, states, and countries.

And so we've come a long way from Thales, from measuring the earth and finding unknown places to measuring changes in places and rediscovering old places that change and renew themselves or die because of the processes that connected them.

The cliche about time is that those who are ignorant of history are doomed to repeat its mistakes. Similarly, those who are ignorant about geography and memorize capitals are doomed to live less interesting lives in places they don't understand, and die of boredom. Know your place!

Invention of the silk hat led to the formationof many smalllakes and bogsin the United States.

The U.S. policy of repatriating Haitians may wellbe driven by thepattern of thespread of AIDS.

American threats to build walls on the Mexicanboundary are assilly as the GreatWall of China.

Serenity seems to lull governments anduniversities andlead them todevalue geography.

GEORGE DEMKO is director of the Rockefeller Centerfor Public Policy and author of The Why of Where: Adventures in Geography.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureCure1 For The Common Cold2 Proven3 At Dartmouth4!

December 1992 By TIG TILLINGHAST '93 -

Cover Story

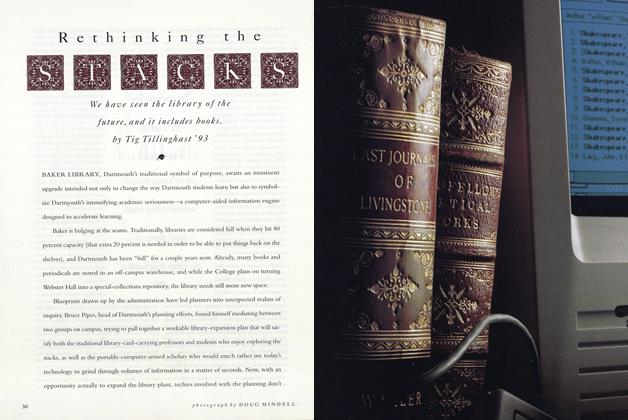

Cover StoryThe Library Culture

December 1992 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe Ether Library

December 1992 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryRethinking The Stacks

December 1992 By Tig Tillinghast '93 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryWith Hard-bound Books, Who Needs Digital?

December 1992 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryTechnology Now and in the Future

December 1992

Features

-

Feature

FeatureSUMMER TEMPO IS GO-GO-GO

OCTOBER 1965 -

Feature

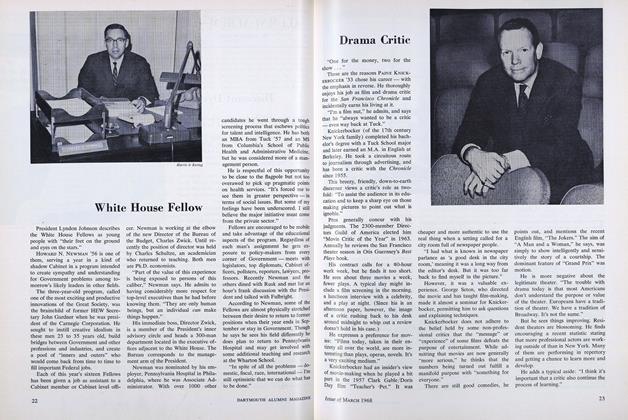

FeatureWhite House Fellow

MARCH 1968 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryWe Are Not Your Indians

APRIL 1997 By Arvo Mikkanen '83 -

Feature

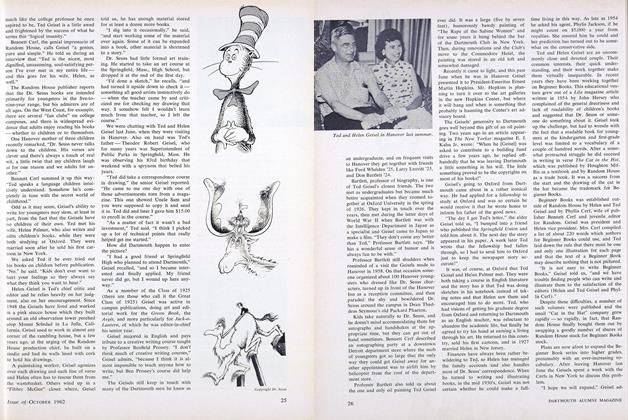

FeatureDr. Seuss

OCTOBER 1962 By CLIFFORD L. JORDAN '45 -

Feature

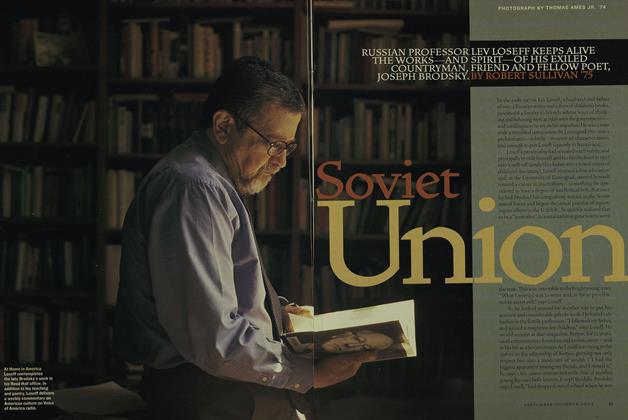

FeatureSoviet Union

Sept/Oct 2005 By ROBERT SULLIVAN ’75 -

Feature

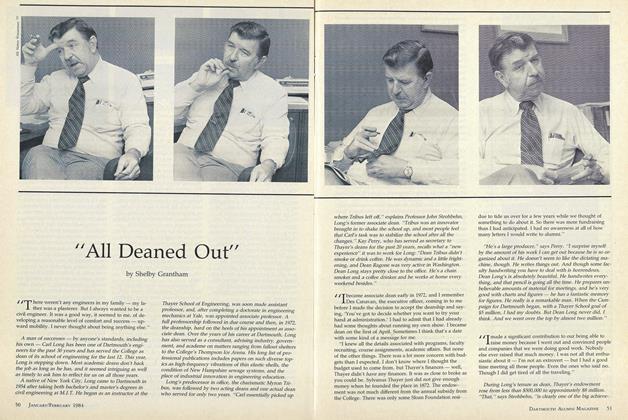

Feature"All Deaned Out"

JANUARY/FEBRUARY 1984 By Shelby Grantham