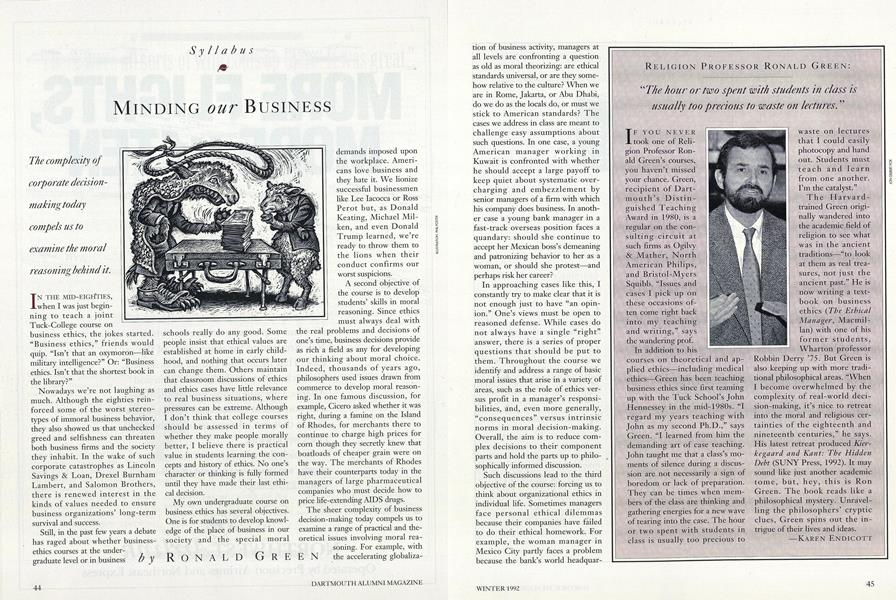

The complexity of corporate decision-making today compels us to examine the moral reasoning behind it.

IN THE MID-EIGIHTIES, when I was just beginning to teach a joint Tuck-College course on business ethics, the jokes started. "Business ethics," friends would quip. "Isn't that an oxymoron—like military intelligence?" Or: "Business ethics. Isn't that the shortest book in the library?"

Nowadays we're not laughing as much. Although the eighties reinforced some of the worst stereotypes of immoral business behavior, they also showed us that unchecked greed and selfishness can threaten both business firms and the society they inhabit. In the wake of such corporate catastrophes as Lincoln Savings & Loan, Drexel Burnham Lambert, and Salomon Brothers, there is renewed interest in the kinds of values needed to ensure business organizations' long-term survival and success.

Still, in the past few years a debate has raged about whether business-ethics courses at the undergraduate level or in business schools really do any good. Some people insist that ethical values are established at home in early childhood, and nothing that occurs later can change them. Others maintain that classroom discussions of ethics and ethics cases have little relevance to real business situations, where pressures can be extreme. Although I don't think that college courses should be assessed in terms of whether they make people morally better, I believe there is practical value in students learning the concepts and history of ethics. No one's character or thinking is fully formed until they have made their last ethical decision.

My own undergraduate course on business ethics has several objectives. One is for students to develop knowledge of the place of business in our society and the special moral demands imposed upon the workplace. Americans love business and they hate it. We lionize successful businessmen like Lee lacocca or Ross Perot but, as Donald Keating, Michael Milken, and even Donald Trump learned, we're ready to throw them to the lions when their conduct confirms our worst suspicions.

A second objective of the course is to develop students' skills in moral reasoning. Since ethics must always deal with the real problems and decisions of one's time, business decisions provide as rich a field as any for developing our thinking about moral choice. Indeed, thousands of years ago, philosophers used issues drawn from commerce to develop moral reasoning. In one famous discussion, for example, Cicero asked whether it was right, during a famine on the Island of Rhodes, for merchants there to continue to charge high prices for corn though they secretly knew that boatloads of cheaper grain were on the way. The merchants of Rhodes have their counterparts today in the managers of large pharmaceutical companies who must decide how to price life-extending AIDS drugs.

The sheer complexity of business decision-making today compels us to examine a range of practical and theoretical issues involving moral reasoning. For example, with the accelerating globalization of business activity, managers at all levels are confronting a question as old as moral theorizing: are ethical standards universal, or are they somehow relative to the culture? When we are in Rome, Jakarta, or Abu Dhabi, do we do as the locals do, or must we stick to American standards? The cases we address in class are meant to challenge easy assumptions about such questions. In one case, a young American manager working in Kuwait is confronted with whether he should accept a large payoff to keep quiet about systematic overcharging and embezzlement by senior managers of a firm with which his company does business. In another case a young bank manager in a fast-track overseas position faces a quandary: should she continue to accept her Mexican boss's demeaning and patronizing behavior to her as a woman, or should she protest—and perhaps risk her career?

In approaching cases like this, I constantly try to make clear that it is not enough just to have "an opinion." One's views must be open to reasoned defense. While cases do not always have a single "right" answer, there is a series of proper questions that should be put to them. Throughout the course we identify and address a range of basic moral issues that arise in a variety of areas, such as the role of ethics versus profit in a manager's responsibilities, and, even more generally, "consequences" versus intrinsic norms in moral decision-making. Overall, the aim is to reduce complex decisions to their component parts and hold the parts up to philosophically informed discussion.

Such discussions lead to the third objective of the course: forcing us to think about organizational ethics in individual life. Sometimes managers face personal ethical dilemmas because their companies have failed to do their ethical homework. For example, the woman manager in Mexico City partly faces a problem because the bank's world headquarters (1) hasn't properly prepared her for the unique Mexican cultural environment (as some would say), or (2) hasn't done its job of establishing uniform standards for the treatment of women managers (as others might argue). Wherever one comes out on the specifics, this case has an organizational as well as an individual dimension.

I like to end all my teaching in business ethics with a case entitled "The Parable of the Sadhu," written several years ago by Wall Street executive Buzz McCoy about an unsettling experience he had during an expedition in the Himalayas. McCoy and his trekking companions faced a difficult decision.

Another group had left them with a Hindu holy man, a sadhu, who had been found lying unconscious in the snow. McCoy and his companions were forced to ask themselves: should they give up the culminating experience of their six-month-long trek to bring the sadhu all the way back to civilization, or was it enough that they saw the sadhu down to a safer place on the mountainside?

On the surface, this case has nothing to do with business. It raises eternal questions about our moral responsibilities to others—am I my brother's or sister's keeper?—and it reminds us of age-old religious texts and teachings. Yet the case is also about business. As McCoy makes clear, it is a parable about individual ethical responsibility in large organizations. Why, in the context of a group, do nice people—McCoy himself is an elder in the Presbyterian Church—sometimes do things that violate their deepest values and cause regret for years to come?

From the safety of the classroom we confront the kinds of ethical challenges Buzz McCoy faced.

Developing reasoning skills and thinking about tough cases in advance is one way of avoiding mistakes when students move from the classroom to the icy mountainsides of the real world.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

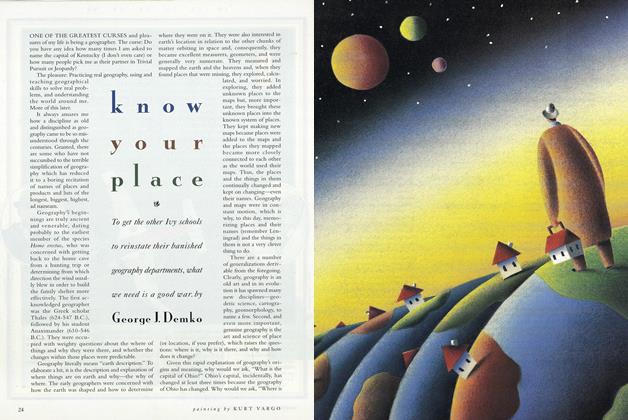

FeatureKnow Your Place

December 1992 By George J.Demko -

Feature

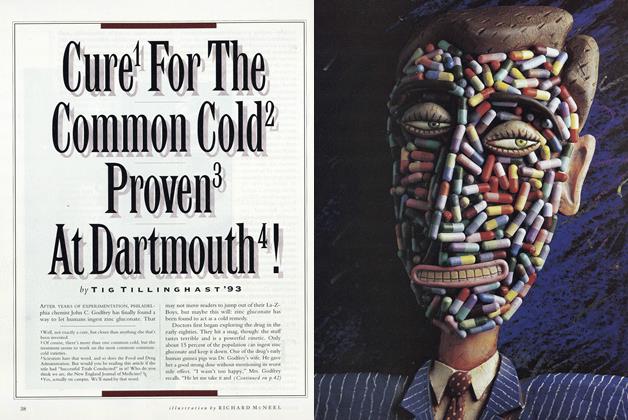

FeatureCure1 For The Common Cold2 Proven3 At Dartmouth4!

December 1992 By TIG TILLINGHAST '93 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe Library Culture

December 1992 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe Ether Library

December 1992 -

Cover Story

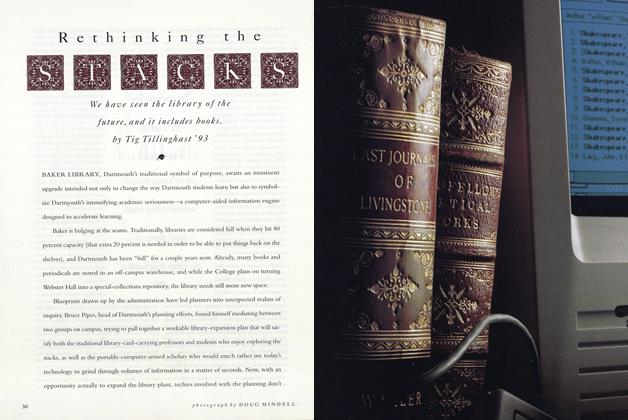

Cover StoryRethinking The Stacks

December 1992 By Tig Tillinghast '93 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryWith Hard-bound Books, Who Needs Digital?

December 1992

Article

-

Article

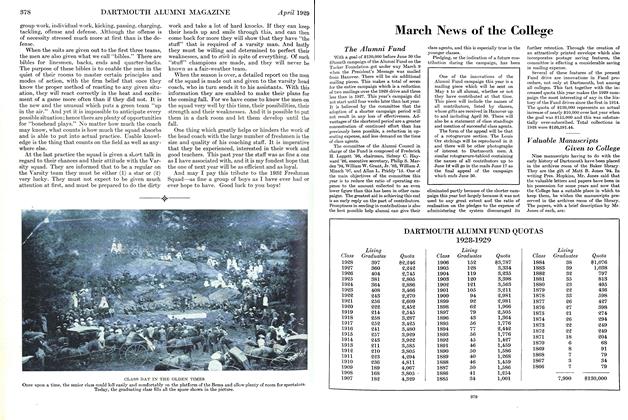

ArticleValuable Manuscripts Given to College

APRIL 1929 -

Article

ArticleSenior Fellows Named

May 1933 -

Article

ArticleThe Computer as Librarian.

FEBRUARY 1967 -

Article

ArticleTwo new Trustees elected

MAY 1984 -

Article

ArticleProfessor John A. Menge: Will Dartmouth be Facing a Budget Crisis Like Stanford and Yale?

MAY 1992 -

Article

ArticleAudacious Questions

MAY 1984 By Laurie Kretchmar '84