" When it comes to death ...we are all dealing with the unknown. "

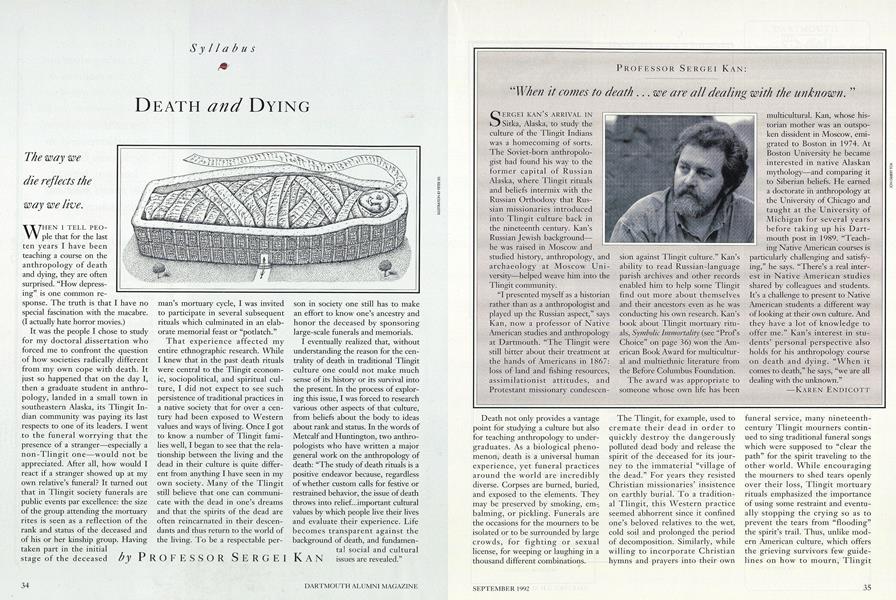

SERGEI KAN'S ARRIVAL IN Sitka, Alaska, to study the culture of the Tlingit Indians was a homecoming of sorts. The Soviet born anthropologist had found his way to the former capital of Russian Alaska, where Tlingit rituals and beliefs intermix with the Russian Orthodoxy that Russian missionaries introduced into Tlingit culture back in the nineteenth century. Kan's Russian Jewish backgroundhe was raised in Moscow and studied history, anthropology, and archaeology at Moscow University helped weave him into the Tlingit community.

"I presented myself as a historian rather than as a anthropologist and played up the Russian aspect," says Kan, now a professor of Native American studies and anthropology at Dartmouth. "The Tlingit were still bitter about their treatment at the hands of Americans in 1867: loss of land and fishing resources, assimilationist attitudes, and Protestant missionary condescension sion against Tlingit culture." Kan's ability to read Russian language parish archives and other records enabled him to help some Tlingit find out more about themselves and their ancestors even as he was conducting his own research. Kan's book about Tlingit mortuary rituals, Symbolic Immortality (see "Prof's Choice" on page 36) won the American Book Award for multicultural and multiethnic literature from the Before Columbus Foundation.

The award was appropriate to someone whose own life has been multicultural. Kan, whose historian mother was an outspoken dissident in Moscow, emigrated to Boston in 1974. At Boston University he became interested in native Alaskan mythology and comparing it to Siberian beliefs. He earned a doctorate in anthropology at the University of Chicago and taught at the University of Michigan for several years before taking up his Dartmouth post in 1989. "Teaching Native American courses is particularly challenging and satisfying," he says. "There's a real interest in Native American studies shared by colleagues and students. It's a challenge to present to Native American students a different way of looking at their own culture. And they have a lot of knowledge to offer me." Kan's interest in students' personal perspective also holds for his anthropology course on death and dying. "When it comes to death," he says, "we are all dealing with the unknown."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureSecond Chances

September 1992 By Mary Cleary Kiely '79 -

Feature

FeatureFishing The River For A Monument

September 1992 By John Scotford '38 -

Feature

FeatureTo An Athlete, Aging

September 1992 By Mark Lange '84 -

Feature

FeatureCommunion With The High Places

September 1992 By Andrew Daniels '85 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryChoices

September 1992 By Jay Heinrichs -

Article

ArticleDr. Wheelock's Journal

September 1992 By "E. Wheelock"

Karen Endicott

-

Article

ArticleProfessor of Economics William L. Baldwin

NOVEMBER 1992 By Karen Endicott -

Article

ArticleHold that Curriculum

June 1993 By Karen Endicott -

Article

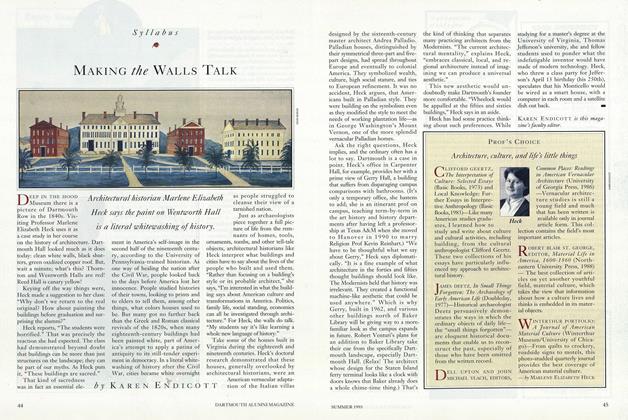

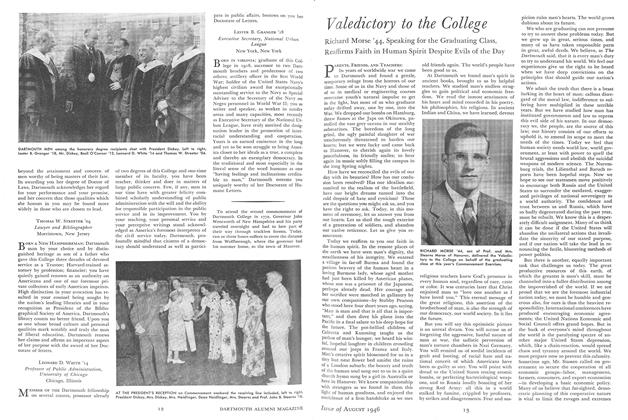

ArticleMaking the Walls Talk

June 1993 By Karen Endicott -

Article

ArticlePatient Talk

September 1993 By Karen Endicott -

Article

ArticleSound Words

FEBRUARY 1994 By Karen Endicott -

Article

ArticleFilling The Power Vacuum

June 1994 By Karen Endicott

Article

-

Article

ArticleFootball Captain Elected

January, 1911 -

Article

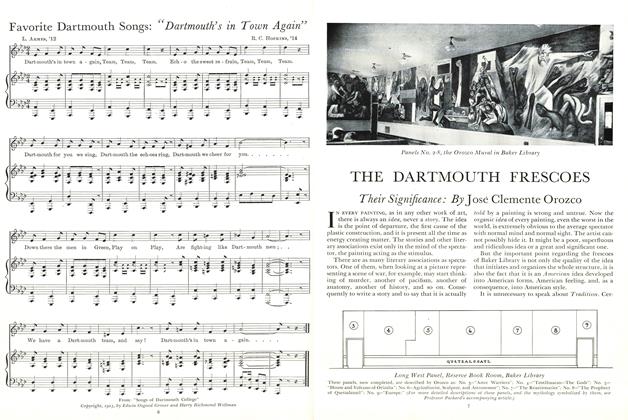

ArticleFavorite Dartmouth Songs: "Dartmouth's in Town Again"

November 1933 -

Article

ArticleParting Counsel

August 1946 -

Article

ArticleThe Faculty

February 1939 By E. P. K. -

Article

ArticleDiary of a Commuter

DECEMBER 1965 By L.G. -

Article

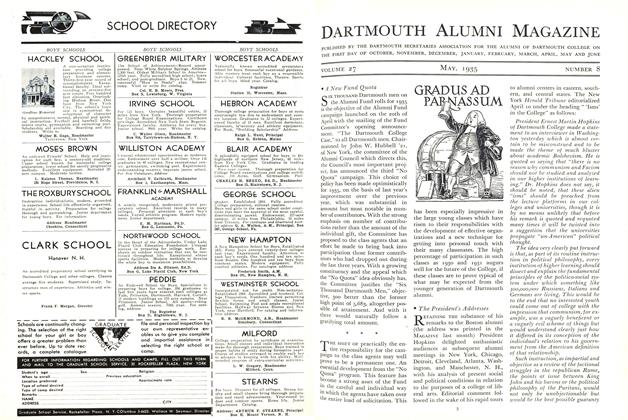

ArticleThe President's Addresses

May 1935 By The Editors