Beyond the TajMahal and theTemple of Doomlie the truerportraits of India.

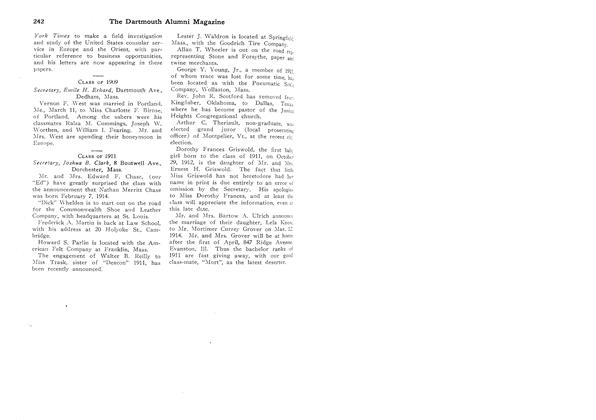

WHEN I ASK MY STUDENTS what they know of India at the beginning of my courses, many of them initially draw a blank. After I press them a bit, however, they come up with a multitude of images and assumptions about the subcontinent. India to them is a land of desperate poverty and a spiralling population, of the caste system and widow burning, of naked holy men and intense spirituality, of Indian princes and the Taj Mahal. Such images have become so powerfully entrenched in our culture that they overwhelm alternative images that would be essential to a well-rounded picture of South Asia. Few Americans think of India as having its own space and nuclear programs, an extensive higher education system, an industrial economy geared to consumer consumption, an agrarian economy whose growth consistently outstrips the expansion in its population, and the secondlargest middle class in the world.

Images, literary themes, and assumptions hundreds of years old have been reproduced so often that it is difficult for us to rethink our understandings of South Asian society. Moviegoers who watched "Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom" may not have realized how the story of the Thugs a group of bandits who supposedly worshipped the malevolent goddess Kali and engaged in human sacrifice had been the subject of dozens of books and many movies since the early nineteenth century. Today some historians argue that the Thuggee cult never existed except in the minds of the British rulers, who considered the widespread banditry of the early colonial period to be part of an organized conspiracy with a sinister cultural character.

Thus, to understand South Asia, or any other non-Western society for that matter, it is useful first to "unlearn" much of what our culture has taught us about that society. One means to such unlearning is to explore the idea of India as it has been generated and reproduced in European literature, scholarship, and visual media from the sixteenth century to the present.

This process of imagining the Orient has gone through four major phases during the past 500 years. During the first phase, which we might call the Age of the Marvelous, the chief images of South Asia came from the accounts of travelers of the sixteenth, seventeenth, and eighteenth centuries. These adventurers, mostly traders, missionaries, and emissaries from the European courts, portrayed India as a land of fantastic wealth, with barbarous rulers and abhorrent social practices.

During the second phase, the Age of Orientalism of the late eighteenth century, scholars and painters began to take an increased interest in capturing India for their European audiences. Scholars learned Sanskrit, Persian, and the vernacular languages and found in India a rich intellectual tradition that they felt was worthy of their admiration. Artists relayed to Europe paintings of beautiful landscapes and impressive architecture. But the Orientalists based their understandings on religious texts and on great monuments (such as the Taj Mahal) rather than on the lived reality of ordinary human beings, and in the process created an image of India as exotic, otherworldly, and spiritual. Moreover, they usually contrasted an imagined Golden Age of the past with what they felt to be the social degradation of the Indian present.

The third phase of imagining the Orient was the heyday of the British empire during the late nineteenth century. The European sense of racial and cultural superiority had reached its height; stereotypes of Indian backwardness, divisiveness, and incapacity for self-rule were bolstered by colonial science and anthropology. British officials amassed information on the "tribes and castes" of India that continues to shape stereotypes of particular groups today. Ethnographers developed elaborate theories of racesome attempted to relate cranial measurements to behavioral patterns and intelligence; photographic images supposedly confirmed their findings. Rudyard Kipling's writings projected the era's imperial sense of self-confidence.

In the fourth phase, the Age of Modernity from the period between the world wars to the present many of the most overt racial stereotypes of the previous period have given way, but Europeans and Americans continue to judge India by standards of what is modern and "progressive," and often find the country wanting. Thus, in the work of V.S. Naipaul and many other current writers, India is seen as a traditional society whose time-honored beliefs and customs hinder movement into the modern age.

In each of these four phases, India has been interpreted in light of the larger ideological preoccupations of the time; but Westerners in each period continuously built upon the intellectual and cultural foundations provided by its predecessors. I hope that after examining the development of these European images, students will constantly question the images they receive in film, popular novels and in the news about India and about the world's other societies and social groups. ("Prof's Choice " appears on page 40.)

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

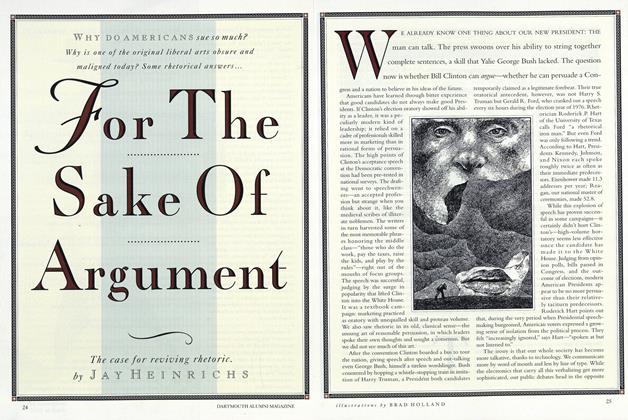

FeatureFor The Sake Of Argument

February 1993 By Jay Heinrichs -

Feature

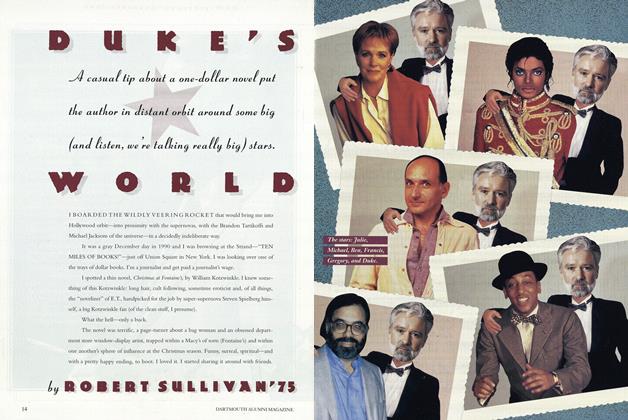

FeatureDUKE'S WORLD

February 1993 By ROBERT SULLIVAN '75 -

Feature

FeatureRoller Screaming

February 1993 By John Morton -

Feature

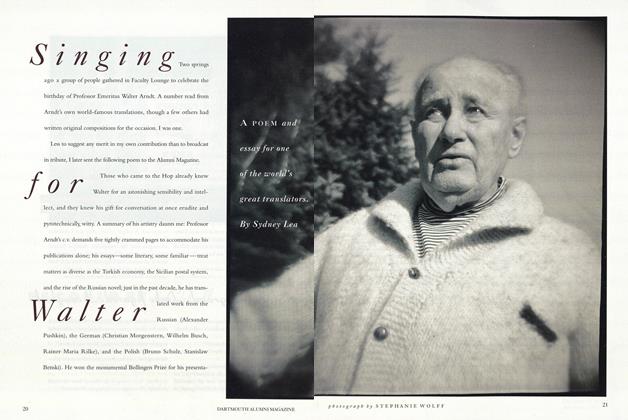

FeatureSinging for Walter

February 1993 By Sydney Lea -

Article

ArticleThe Idealist a Leader

February 1993 By James O. Freedman -

Class Notes

Class Notes1983

February 1993 By Kenneth M. Johnson