"Our need for heroesis as timely asour most recentmoment of personaldoubt or despair."

TODAY'S FRESHMEN ARE part of the first generation to enter college after the collapse of communism and the end of the Cold War. After several generations of Cold War leaders who were perforce tough-minded realists, perhaps now we are prepared for an era of leaders who are idealists.

The term "idealist" is an old-fashioned one a person who seeks what Yeats called "perfection of the life, or of the work" but the need for heroes with the capacity to elevate our sights and ennoble our efforts is as timely as our most recent moment of personal doubt or despair.

At Convocation last fall I spoke to students about an idealist whose achievements make him a hero in my own life, the playwright Vaclav Havel, who was until last July president of Czechoslovakia.

Born in Prague in 1936, Havel worked briefly in a chemical laboratory while preparing himself for a life in the theater, first as critic and later as playwright. Havel's plays bear the special moral qualities of one who has observed with ironic wit the absurdities of political orthodoxy and the gibberish of bureaucratic hypocrisy.

When, in August 1968, the reforms of the Prague Spring were crushed by Soviet tanks, Havel broadcast to his countrymen, from an underground radio station, an urgent plea for resistance. While many other writers and artists chose to collaborate with the communist dictatorship, Havel did not, and for the next 20 years he vigorously opposed the totalitarian domination of his country. His criticism of the communist government for its suppression of human freedoms resulted in the banning of his plays, revocation of his passport, and repeated prison sentences. By December 1989, when the so-called Velvet Revolution succeeded in throwing off communist rule, Havel's longtime status as a dissident had given him a moral stature that stamped him as a symbol of civic courage and fresh ideas. As a result, he was catapulted into the presidency.

Archibald MacLeish wrote of Hemingway, derisively, that "Fame became of him." By contrast, fame did not become of Havel, nor did power seduce him. Last summer, after he lost a parliamentary vote on preserving the Czechoslovak union, Havel accepted the people's verdict and relinquished power as gracefully and unpretentiously as he had assumed it.

Central to Vaclav Havel's life both as a private and a public person has been a commitment to personal responsibility: the moral obligation of individuals to serve others and to recognize "the special radioactive power of the truthful word." In an arresting speech to a joint session of the United States Congress in 1990, he argued that politics was ultimately about die choices that individual men and women make not choices to exercise individual rights, but choices to accept individual moral responsibility.

Havel's capacity for stating moral truths in political terms has instructed us that the language of democratic leaders does not need to be fitted to sound bites or targeted at some lowest common denominator. When Havel asserts that "decency and courage make sense, that something must be risked in the struggle against dirty tricks," his words engage our imagination. When he writes, "Those who find themselves in politics therefore bear a heightened responsibility for the moral state of society," his words resonate in our souls.

There are other lessons, too, that may be drawn from Havel's example: that a respect for the power of language can breed a simple eloquence more mighty than armies; that leaders of modern nations who write their own speeches, rather than permitting others to do it for them, are much more likely to tell their fellow citizens the truth; that in mature men and women, conscience, morality, and idealism are of a piece.

If it is true, as Edmund Burke wrote, that "example is the school of mankind; they will learn at no other," Vaclav Havel is an elevating example for our students and the world of an idealist who taught us that intellectuals possess the stuff of political responsibility and personal greatness. Indeed, in all of contemporary politics, I know of no better example than Havel of the civilizing force and transcendent power of the liberal arts.

In closing, I urged the audience to consider the example of Vaclav Havel in personal terms. I said, "Who could have foretold, when Vaclav Havel was 18 years old, that he held in the smithy of his soul such potential for greatness? Who could have foretold then that, by virtue of his idealism and self-discipline, he would one day make a hallowing contribution not only to literature but also to freedom?

"Who can be certain now that some of you even as you feel young, untested, and apprehensive about what lies in store may not come, through hard work and destiny, to make contributions to your society that equal those of Vaclav Havel?

"Women and men of Dartmouth, few of your contemporaries stand in so auspicious a position as you to advance the human condition by idealism. Few have been granted talent and privilege in such generous measure as each of you has. What you make of that talent, what you do with that privilege, is a test of your character. Meeting that test, especially with the examples of your own heroes before you, is one of life's most satisfying achievements."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureFor The Sake Of Argument

February 1993 By Jay Heinrichs -

Feature

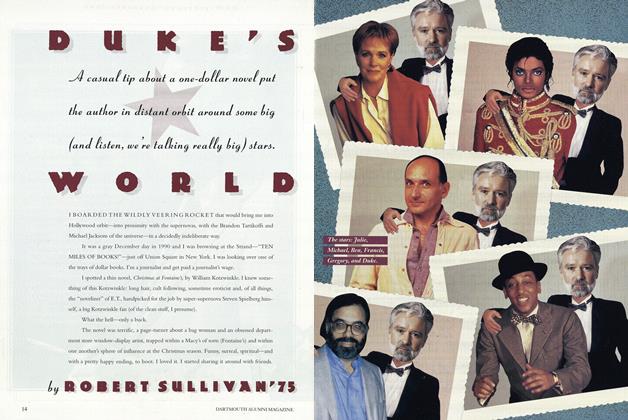

FeatureDUKE'S WORLD

February 1993 By ROBERT SULLIVAN '75 -

Feature

FeatureRoller Screaming

February 1993 By John Morton -

Feature

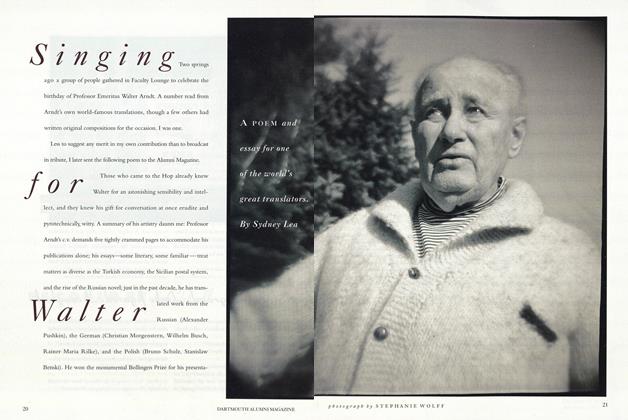

FeatureSinging for Walter

February 1993 By Sydney Lea -

Article

ArticleImagining the Orient

February 1993 By Douglas Haynes -

Class Notes

Class Notes1983

February 1993 By Kenneth M. Johnson

James O. Freedman

-

Cover Story

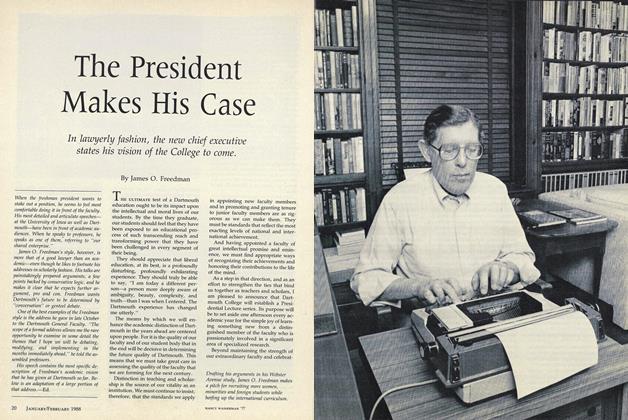

Cover StoryThe President Makes His Case

FEBRUARY • 1988 By James O. Freedman -

Article

ArticleCOACHES AND PRESIDENTS

OCTOBER 1990 By James O. Freedman -

Article

ArticleTHE PROFESSOR'S LIFE

FEBRUARY 1991 By James O. Freedman -

Article

ArticleON PERSONAL DISTINCTION

OCTOBER 1991 By James O. Freedman -

Feature

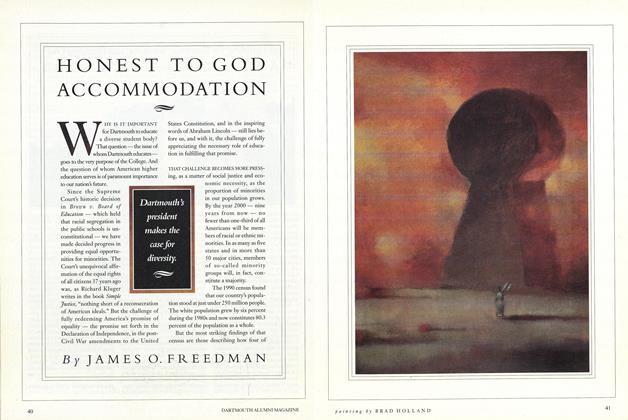

FeatureHONEST TO GOD ACCOMMODATION

OCTOBER 1991 By JAMES O. FREEDMAN -

Article

ArticleA Comprehensive Overhaul

October 1992 By James O. Freedman

Article

-

Article

ArticleCommencement June 16

March 1940 -

Article

ArticleAlumni Council Meeting

November 1946 -

Article

ArticleThayer School on Top

January 1956 -

Article

ArticleSign of the Times

JANUARY 1999 -

Article

ArticleHow Twain Turned Vaudeville on its Ear

MARCH 1989 By David Birney -

Article

ArticleThayer School

December 1944 By William P. Kimball '29