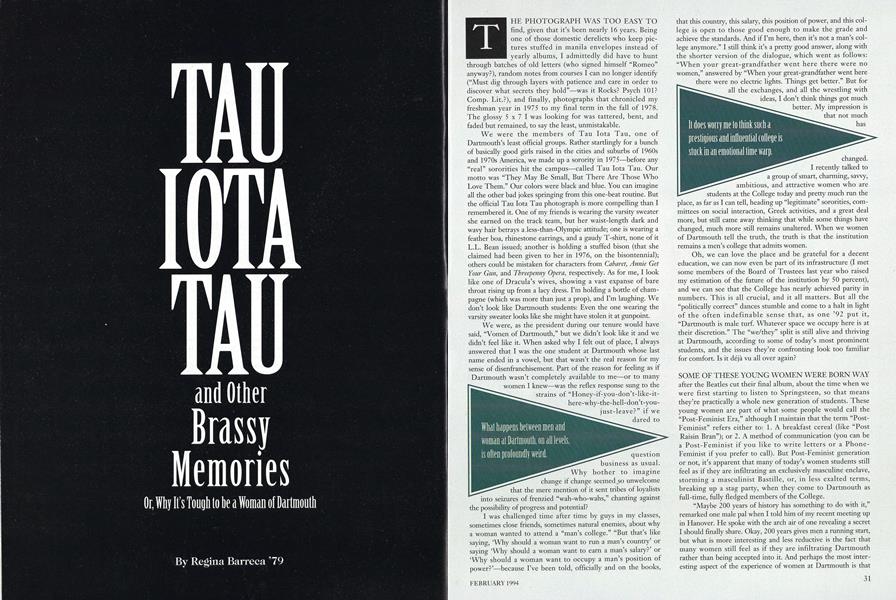

TAU IOTA TAU and other Brassy Memories Or, Why It's Tough to be a Woman of Dartmouth

THE PHOTOGRAPH WAS TOO EASY TO find, given that it's been nearly 16 years. Being one of those domestic derelicts who keep pictures stuffed in manila envelopes instead of yearly albums, I admittedly did have to hunt through batches of old letters (who signed himself "Romeo" anyway?), random notes from courses I can no longer identify ("Must dig through layers with patience and care in order to discover what secrets they hold"—was it Rocks? Psych 101? Comp. Lit.?), and finally, photographs that chronicled my freshman year in 1975 to my final term in the fall of 1978. The glossy 5x71 was looking for was tattered, bent, and faded but remained, to say the least, unmistakable.

We were the members of Tau lota Tau, one of Dartmouth's least official groups. Rather startlingly for a bunch of basically good girls raised in the cities and suburbs of 1960s and 1970s America, we made up a sorority in 1975—before any "real" sororities hit the campus—called Tau lota Tau. Our motto was "They May Be Small, But There Are Those Who Love Them." Our colors were black and blue. You can imagine all the other bad jokes springing from this one-beat routine. But the official Tau lota Tau photograph is more compelling than I remembered it. One of my friends is wearing the varsity sweater she earned on the track team, but her waist-length dark and wavy hair betrays a.less-than-Olympic attitude; one is wearing a feather boa, rhinestone earrings, and a gaudy T-shirt, none of it L.L. Bean issued; another is holding a stuffed bison (that she claimed had been given to her in 1976, on the bisontennial); others could be mistaken for characters from Cabaret, Annie GetYour Gun, and Threepenny Opera, respectively. As for me, I look like one of Dracula's wives, showing a vast expanse of bare throat rising up from a lacy dress. I'm holding a bottle of champagne (which was more than just a prop), and I'm laughing. We don't look like Dartmouth students: Even the one wearing the varsity sweater looks like she might have stolen it at gunpoint.

We were, as the president during our tenure would have said, "Vomen of Dartmouth," but we didn't look like it and we didn't feel like it. When asked why I felt out of place, I always answered that I was the one student at Dartmouth whose last name ended in a vowel, but that wasn't the real reason for my sense of disenfranchisement. Part of the reason for feeling as if Dartmouth wasn't completely available to me or to many women I knew was the reflex response sung to the strains of "Honey-if-you-don't-like-it- here-why-the-hell-don't-you- just-leave?" if we dared to business as usual. Why bother to imagine change if change seemed so unwelcome that the mere mention of it sent tribes of loyalists into seizures of frenzied "wah-who-wahs," chanting against the possibility of progress and potential?

I was challenged time after time by guys in my classes, sometimes close friends, sometimes natural enemies, about why a woman wanted to attend a "man's college." "But that's like saying, 'Why should a woman want to run a man's country' or saying 'Why should a woman want to earn a man's salary?' or 'Why should a woman want to occupy a man's position of power?' because I've been told, officially and on the books, that this country, this salary, this position of power, and this college is open to those good enough to make the grade and achieve the standards. And if I'm here, then it's not a man's college anymore." I still think it's a pretty good answer, along with the shorter version of the dialogue, which went as follows: "When your great-grandfather went here there were no women," answered by "When your great-grandfather went here there were no electric lights. Things get better." But for all the exchanges, and all the wrestling with ideas, I don't think things got much better. My impression is that not much has Changed.

5$ BH I recently talked to a group of smart, charming, savvy, ambitious, and attractive women who are students at the College today and pretty much ran the place, as far as I can tell, heading up "legitimate" sororities, com- mittees on social interaction, Greek activities, and a great deal more, but still came away thinking that while some things have changed, much more still remains unaltered. When we women of Dartmouth tell the truth, the truth is that the institution remains a men's college that admits women.

Oh, we can love the place and be grateful for a decent education, we can now even be part of its infrastructure (I met some members of the Board of Trustees last year who raised my estimation of the future of the institution by 50 percent), and we can see that the College has nearly achieved parity in numbers. This is all crucial, and it all matters. But all the "politically correct" dances stumble and come to a halt in light of the often indefinable sense that, as one '92 put it, "Dartmouth is male turf. Whatever space we occupy here is at their discretion." The "we/they" split is still alive and thriving at Dartmouth, according to some of today's most prominent students, and the issues they're confronting look too familiar for comfort. Is it deja vu all over again?

SOME OF THESE YOUNG WOMEN WERE BORN WAY after the Beatles cut their final album, about the time when we were first starting to listen to Springsteen, so that means they're practically a whole new generation of students. These young women are part of what some people would call the "Post-Feminist Era," although I maintain that the term "Post-Feminist" refers either to: 1. A breakfast cereal (like "Post Raisin Bran"); or 2. A method of communication (you can be a Post-Feminist if you like to write letters or a Phone-Feminist if you prefer to call). But Post-Feminist generation or not, it's apparent that many of today's women students still feel as if they are infiltrating an exclusively masculine enclave, storming a masculinist Bastille, or, in less exalted terms, breaking up a stag party, when they come to Dartmouth as fall-time, fully fledged members of the College.

"Maybe 200 years of history has something to do with it," remarked one male pal when I told him of my recent meeting up in Hanover. He spoke with the arch air of one revealing a secret I should finally share. Okay, 200 years gives men a running start, but what is more interesting and less reductive is the fact that many women still feel as if they are infiltrating Dartmouth rather than being accepted into it. And perhaps the most inter- esting aspect of the experience of women at Dartmouth is that they tend to feel less at home and less welcome as the years progress. "When we were freshman, everyone just sort of hung out together," explained one '92. "But now that I'm a senior, what I see is the sexes dividing, with men and women of the same class spending less and less time together. It's a segregated experience. I see my sorority sisters, and I see my own boyfriend, but as for a really integrated social world, no, it just doesn't happen anymore. The men get more and more into their fraternity life, and they tell themselves that this is the last time they'll get to hang out with the boys, and so they do. But it's like the place becomes a boys' school over again by senior year, with them siting around drinking or going hiking. They put up a big emotional sign saying 'no women allowed.' It affects the atmosphere of the institution."

"It's not like we want to take anything away from them," interrupted a '93. "But what comes across is the fear that women will divert attention from the 'male-bonding' they want to do, and that our very presence on campus is unwelcome. They're afraid, I think, that their male buddies will think that they want to spend time with women and so will make fun of them for being 'wimps' or something." "What gets me," interjected a smiling junior, "is that we go out of our way to make the guys feel welcome, and they don't reciprocate. The guys just read over the freshman book every year you know that they call it the 'Shmenu? Rhymes with menu? Geddit? and pick out whoever they think are the cutest girls, invite them to parties. These guys get to date a new set of faces and personalities every year. Can you imagine what a sorority would face if the women picked out the hunkiest guys from the freshman book and invited them over for a raucous party? Good luck."

"One version of the typical Dartmouth man," explained a senior, wearily, "wants to power-boot with his buddies because he thinks this might be the last chance he gets to have a good time. And power-booting constitutes a good time." While this sense of life in Hanover doesn't surprise me, it does worry me to think such a prestigious and influential college is stuck in an emotional time warp, with history bound to repeat itself literally ad nauseam.

No, no, of course you can't legislate people's emotional lives, and you can't make them spend time with folks they don't want to be with, and you can't automatically stop the social life of an Ivy League institution from resembling a C.Y.O. dance, with girls lined up on one side of the gym and guys lined up on the other. No, of course not. And, of course, Dartmouth has a great deal to offer; it certainly changed my life. I learned to speak up and speak out, occasionally to my detriment, but often to my advantage. There were enough excellent professors to outweigh the ones who drank beer during class in order to show they were one of the boys (this really happened, folks, remember?), and these excellent professors not only taught well, they inspired us to go out and make trouble.

What happens between men and women at Dartmouth, on all levels, is often profoundly weird. Sometimes it becomes weirder in retrospect. I remember learning the words to "Dartmouth's in Town Again, Run Girls Run" on my freshman trip but I thought they were talking about other girls, so I laughed along. Here these guys were, explaining the gender-dynamics of my col- lege to me in no uncertain terms, but I thought they were kidding me and so I didn't listen to the words carefully. There I was, "Ha, ha, aren't you witty," when there was no joke. I see now that there never were any "Other" girls, that no women deserved worse treatment than ourselves. I see, too, that instructing women to run and hide from the vast tide of Dartmouth manhood hid deep fear and frustration held by many men, which could only be issued forth in these bastardized college songs under the camouflage of a "gag." These gags, of course, were meant to shut us up, and in most cases they did. You shut up because you didn't want to seem like a bad sport, or a disloyal student, or a priggish "female" who couldn't get a laugh out of life. From what I hear, much of the same routine goes on today. When I asked this group of current

students whether they'd heard the "Run, Girls, Run" version of "Dartmouth's In Town Again," a few admitted that they had; I suspect the others might have heard it, too, but were embarrassed on behalf of the College to say so out loud. Granted, it is a step in the right direction—l never heard the song sung any other way except during concerts at the Hop.

The issues that women have confronted, and that continue to confront women in terms of dealing with Dartmouth, cross class, ethnic, and generational lines. But when the women students of today talk about a sense of being removed from the heart of the College, we should pay attention to the underlying issues they raise. I've taught more than a thousand students during the last eight years at two major universities, and the guys there don't want to stop spending time with the women during senior year. Young men and women don't spend as much time sniffing around each other, fearful that they're being excluded, co-opted, trapped, or damaged as they do in Hanover. They have their own personal issues to deal with, God knows, and I hear enough about broken hearts and terrible relationships to confirm that boys and girls often don't play well together.

But these matters are not institutionalized along gender lines and supported—however unwittingly by the college they attend. The University of Connecticut does not play a particularly significant role in how its women and men interact. When

the College football team gets to sing "Men of Dartmouth" on the field before play even when no one else does, when "cohog" is a phrase heard not only by women in 1975 or even 1985 but by women of the class of 1995 then there's a problem of an inherited nature. You know of inherited problems like something out of Strindberg's Ghosts, for example.

But there is hope. When I participated in a seminar two years ago concerning whether humor was still possible, I returned to Dartmouth for the first time since I graduated in 1978. When Tau lota Tau first sent an obviously playful letter to the Daily Dartmouth about our intentions to start up a sorority, we heard two responses: Why didn't these women have the courage to use their real names? (We had indeed used our real names), and, quite violently, Why are they making fun of our fun? It was a defeating moment. In 1992 I told my Tau lota Tau story and was greeted with laughter and understanding, and not as I feared, with the recurrence of sanctimonious rancor. At the end of the evening, a distinguished man several years my senior came up to me and said, "When my great-grandfather went here, there were no women. When I went here, there were no women." I braced for a cutting remark. "I never realized how much we were missing." We shook hands, and parted as part of a Dartmouth community that even I, skeptic and lifetime member of T au lota Tau, could embrace.

question

It does worry me to think such a prestigious and influenlial college is stuck in an emotional time warp.

These excellent professors not only laught well, they inspired us to go out and make trouble.

We don't look like Dartmouth students: even the one wearing the varsity sweater looks like she might have slolen it at guopoinl.

Regina Barreca, author of They Used to Call Me Snow White...But I Drifted (Penguin, 1992) is an associate professor ofEnglish at the University of Connecticut. Her latest book, Perfect Husbands & Other Fairy Tales), was published last fall byHarmony Books, along with Untamed and Unabashed: Women's Humor in Literature (Wayne State University Press.)She is currently completing The Penguin Book of Women's Humor.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

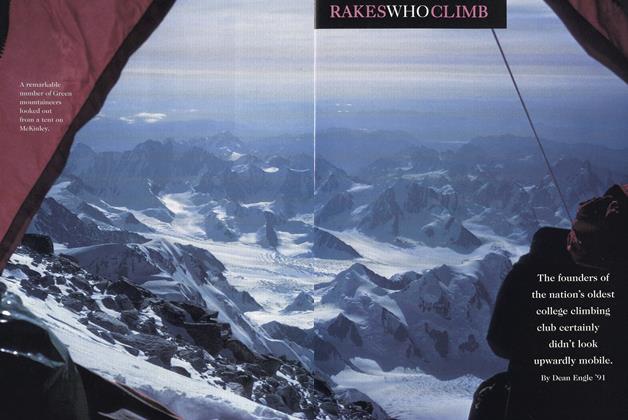

FeatureRAKES WHO CLIMB

February 1994 By Deab Engle '91 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryA leading poet argues that, whether consciously or unconsciously, we all breathe art's air.

February 1994 By Donald Hall -

Feature

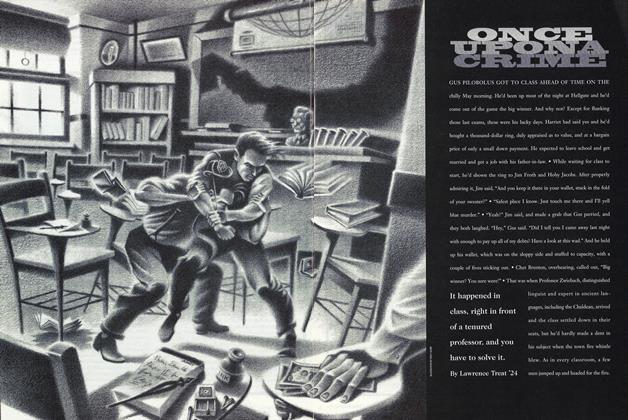

FeatureONCE UPON A CRIME

February 1994 By Lawrence Treat '24 -

Feature

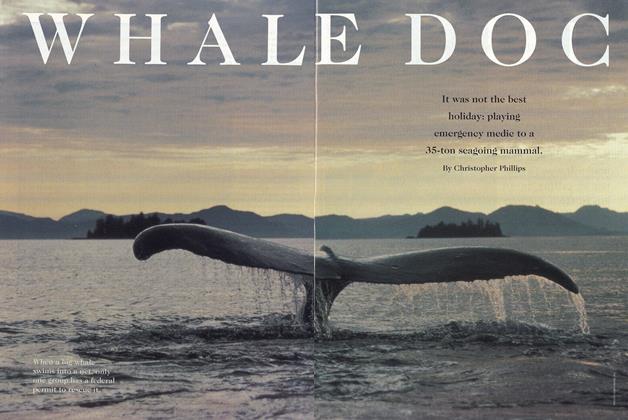

FeatureWHALE DOG

February 1994 By Christopher Phillips -

Article

ArticleDr. WHEELOCK'S JOURNAL

February 1994 By "E. Wheelock" -

Article

ArticleA Year and a Tree, Both Rededicated

February 1994

Regina Barreca '79

-

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorWhither the Greeks?

MAY 1999 -

Feature

FeatureThey Used to Call Me Snow White... But I Drifted

June 1992 By Regina Barreca '79 -

Feature

FeatureThe Next Bus Home

September 1993 By Regina Barreca '79 -

Feature

FeatureAfter Eleven Commencing

June 1995 By Regina Barreca '79 -

Feature

FeatureAfter the FALL

JANUARY 1998 By Regina Barreca '79 -

Feature

FeatureMoney and Luck

MARCH 1999 By Regina Barreca '79

Features

-

Feature

FeatureThe Medical School

April 1975 -

Feature

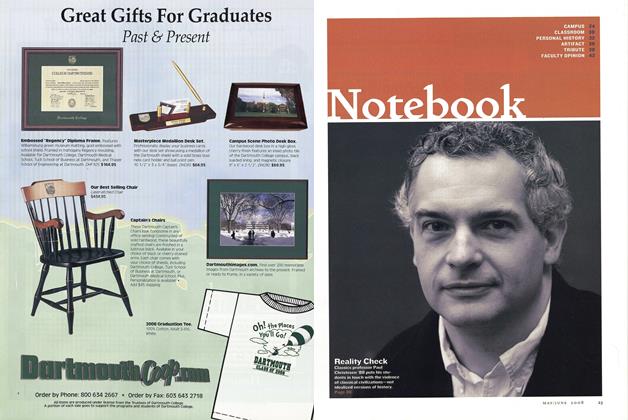

FeatureNotebook

May/June 2008 -

Feature

FeatureDartmouth's Faculty Policies

February 1954 By DONALD H. MORRISON '47h -

Cover Story

Cover StoryColumbia Hailed

MARCH 1995 By Eddie Chamberlain '36 -

Feature

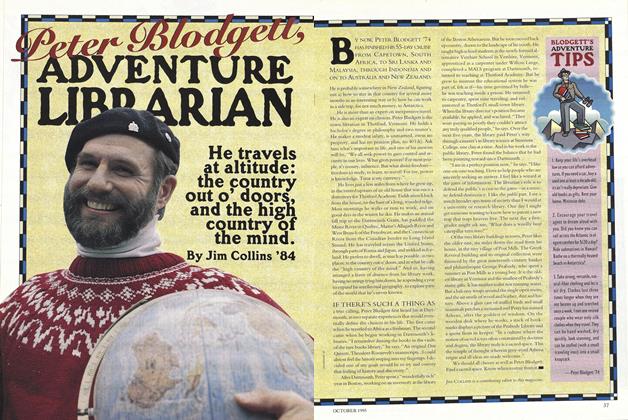

FeaturePeter Blodgutt, Adventure Librarian

October 1995 By Jim Collins '84 -

Feature

Feature"All Deaned Out"

JANUARY/FEBRUARY 1984 By Shelby Grantham