Forget Wet-Down and beanies. Orientation has gone from "The Dartmouth Hand-Book" to confronting the issues of racism, sexism, alcohol, and homophobia.

Few things demonstrate how a campus envisions itself better than the way it indoctrinates its freshmen. When the class of 1940 arrived on campus—in an era when Dartmouth was still ruggedly individualistic—the new students were pretty much on their own to figure out the lay of the land. Their "orientation" came in the form of a little tome published by Green Key, The Dartmouth HandBook, which contained College rules, lore, and advice. There was a free day before classes "for orientation work." And there were library tours.

These days the deans don't even much like the word "orientation." "It is impossible to completely 'orient' students, to provide direction for their entire college career, or even the next nine months," says Assistant Dean of Freshmen Tony Tillman. "The week is really geared towards their initial transition. We provide them with the necessary tools to help them address the challenges they'll meet." The first thing freshmen do is pick up their requisite computers, and they spend much of the rest of the week going to department open-houses and becoming acquainted with campus facilities. But at the end of the week freshmen are now required (or, in deanspeak, strongly urged ) to attend an expanded student-run evening program called "Social Issues at Dartmouth." Upperclassmen perform skits illustrating various social problems such as alcohol abuse, sexism, sexual abuse, racism, and homophobia. Then the freshmen go back to their dorms where their undergraduate advisors (UGAs) lead them in discussion of the skits.

Some alumni have wondered whether these socializing sessions are more propaganda than preparation. Last year the Alumni Council asked for an investigation of the program. Tillman defends the social sessions: "We're not telling anyone how to think or feel, but to respect themselves and their fellow classmates—to not become an obstacle to someone's education." Former Freshman Dean Diana Beaudoin points out that at crucial decision points the scenarios are often "freeze-framed" to generate discussion about how they should end.

Older alumni may always have found freshman week baffling. Thirties graduates who visited campus after the war would find that the traditional rites and hierarchy had been disrupted by relatively hoary freshmen who had been toughened in combat.

Then came the peaceful fifties, when the emphasis was on instilling conformity without coersion and strong-arm tactics.

The social consciousness of the sixties made the very concept of "class unity" seem parochial, and liberal student leaders freed the freshmen from the oppression of traditions like Wet Down and beanies.

With coeducation, an increasingly more diverse campus, and, later, the nation's growing intolerance of sexual assault and alcohol abuse, rules of behavior have become more complex. Orientation has taken on a new purpose: to make the freshmen sensitive to the social issues of the times.

In the early 1980s "social issues" at Dartmouth meant alcohol. An optional evening program called "Drinking (CH3CH2OH): It's up to you" featured students enacting "drinking dilemmas'" and engaging in Phil Donohue-type discussion. But the week also aspired to a loftier scope. A group consisting of faculty, students, and the dean of freshmen conceived a program in which faculty would assign a book for students to read before their arrival on campus and then offer theme lectures during orientation week. The program began in 1983 and continued for tour years to cover a wide range of topics. (The class of 89, for example, explored "Technology and Human Values through lectures on medical ethics, the power of computers, and the assigned reading was Zen and the Art ofMotorcycle Maintenance.) The program sought not only to introduce freshmen to global issues and critical thought but to provide for them a common intellectual experience that would transcend their differences, all in one week. It was a lovely idea, but it didn't work very well. "There were problems with both students and faculty not reading the book," explains Dean Beaudoin. "And figuring out what everyone should read was a more political decision than you would think." Indeed, witness the programs for the final two years: In 1986 the class of 1990's theme was "Diversity: Personal Difference and Cultural Change"; in 1987 the topic was a vaguely suggestive "Transitions," and the book was Lives of Girls and Women. As a failed exercise in promoting a humanist vision, the program dwindled to a circumspect approach to the social problems that were coming to light on campus. Today, the hardiest survivors of the eighties' freshman-week traditions are the socialissues skits.

Surveys taken of students after Freshman Week seem to show that the freshmen themselves like them. "I thought they were good," says Erin Green '94. "Nothing really surprised me—I wasn't thinking Oh my God this happens here?' But it was important to discuss those issues. I think the guys especially need to learn about dating issues."

What else does she remember about the week? "Meeting a lot of people I never spoke to again all year, and everyone traveling around in packs looking for the party.

Plus ca change...

Heather Killebrew is this magazine's alumni news editor. Sheadmits she didn't finish Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance before her freshman week.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureI Was A Freshman Trip Spy

September 1993 By Todd Balf -

Feature

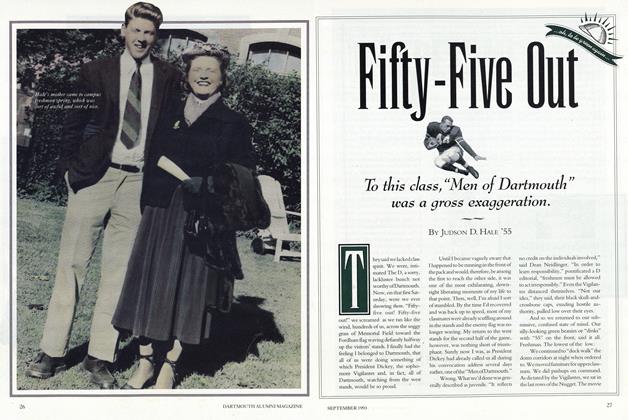

FeatureFifty-Five Out

September 1993 By Judson D. Hale '55 -

Feature

FeatureThe Next Bus Home

September 1993 By Regina Barreca '79 -

Feature

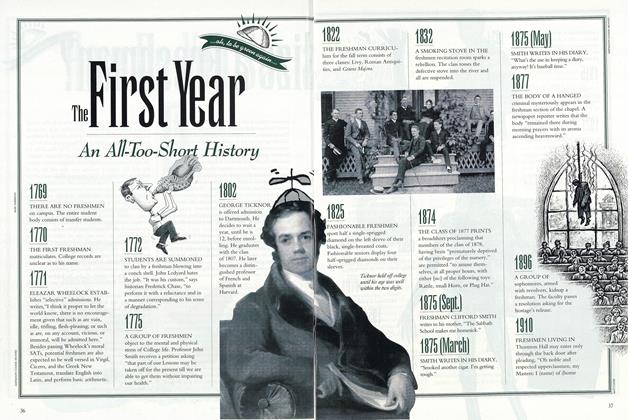

FeatureThe First Year

September 1993 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryThey have been called freshies, Pea Greeners, shmen a current phrase that cannot be uttered without sneering.

September 1993 -

Article

ArticleDr. Wheelock's Journal

September 1993 By "E. Wheelock"

Heather Killebrew '89

-

Article

ArticleA Historic Gift

SEPTEMBER 1991 By Heather Killebrew '89 -

Feature

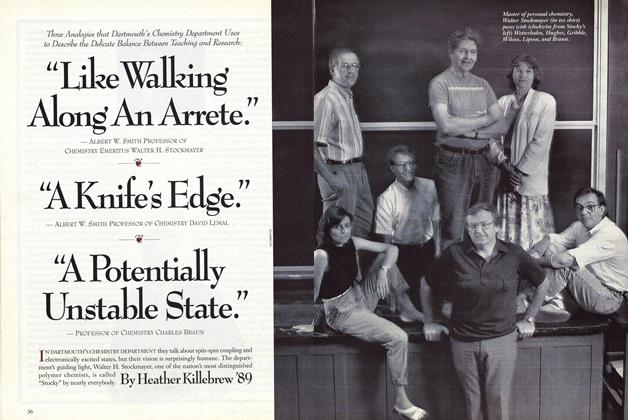

Feature"Like Walking Along an Arrete."

OCTOBER 1991 By Heather Killebrew '89 -

Article

ArticleTalk About Suspense

FEBRUARY 1994 By Heather Killebrew '89 -

Article

ArticleA Keeper of Sheep, by William Carpenter '62

April 1995 By Heather Killebrew '89 -

Article

ArticleOnce Upon a Time

NOVEMBER 1996 By Heather Killebrew '89 -

Feature

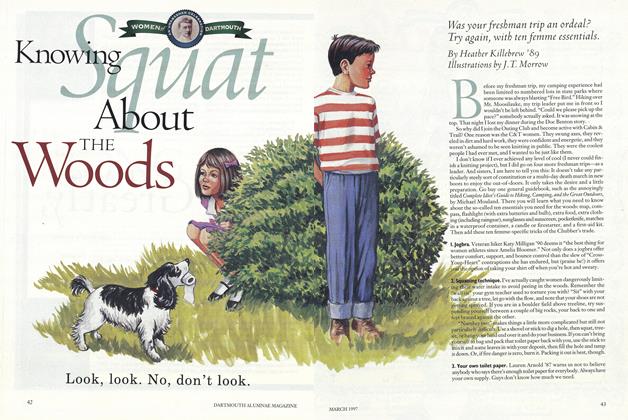

FeatureKnowing Squat About the Woods

MARCH 1997 By Heather Killebrew '89

Features

-

Feature

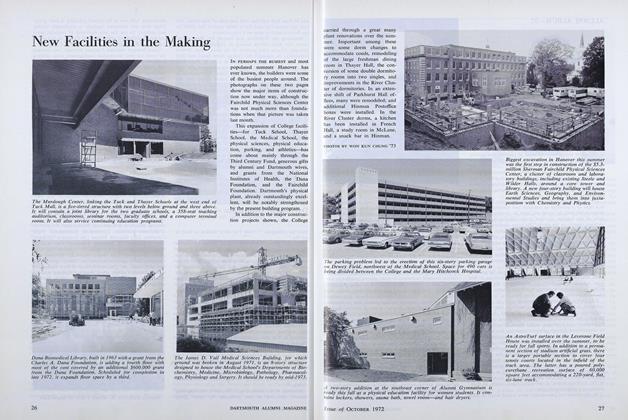

FeatureNew Facilities in the Making

OCTOBER 1972 -

Feature

FeatureFaces in the Gallery

MARCH 1978 -

Feature

FeatureThe Wallace Affair

JUNE 1967 By C.E.W. -

Cover Story

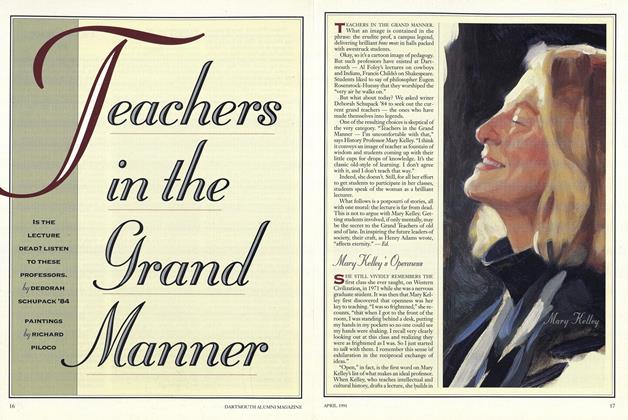

Cover StoryTeachers in the Grand Manner

APRIL 1991 By DEBORAH SCHUPACK '84 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryCanned Lit

MARCH 1995 By Maury Rapf '35 -

Feature

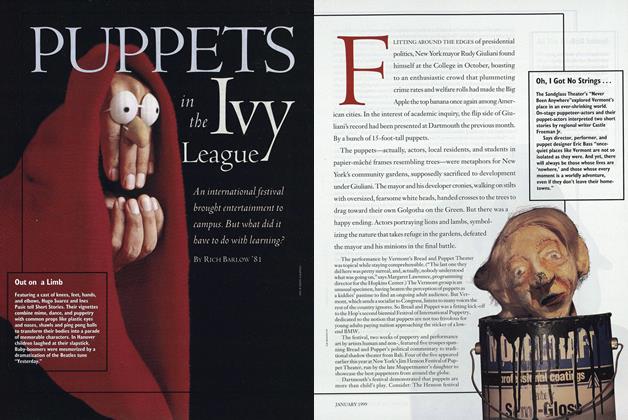

FeaturePuppets in the Ivy League

JANUARY 1999 By Rich Barlow '81