Not so long ago, they were the truest signs of Dartmouth's May.

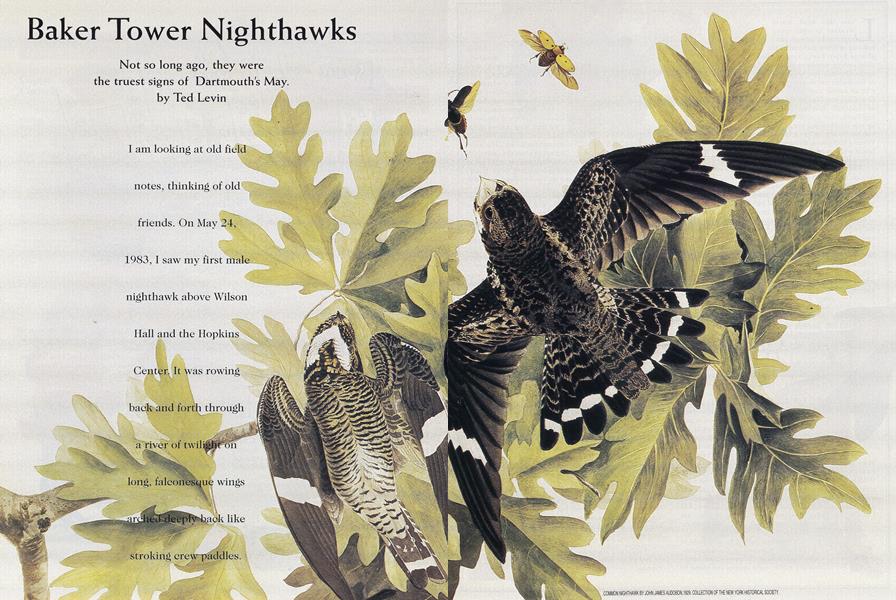

I am looking at old field notes, thinking of old friends. On May 24, 1983, I saw my first male nighthawk above Wilson Hall and the Hopkins Center. It was rowing back and forth through a river of twilight on long, falcohesque wings arched deeply back like stroking crew paddles.

Later that week, warm weather brought more nighthawks through campus—six or seven gathered in the glow of Baker Tower, circling, cirling, circling, mouths open, trolling for moths. One male rose beyond the range of floodlights and then plunged down with an audible snap. I stood at mid-Green, a voyeur fixed on the courtship of another species. First one nighthawk, then a second flew straight up into blackness and plunged earthward beyond the library like a kamikaze pilot. When a bird passed through the lights, its broad white wing bars, one per wing, just beyond the crook, flashed in a semaphore flight.

Only the male nighthawk dove for love. Each time he reached the end of his dive and checked his descent, his stiff primary flight feathers the long, tapered feathers that extend from the outer half of the wing snapped and vibrated like a tuning fork. The air boomed with love notes. The object of all this attention sat like stone on the gravel roof of Kiewit or Mary Hitchcock Hospital, watching, listening, internalizing the performances of each participant. After several swoops toward the female, the male landed, out of view, her.

Fanning his white-banded tail, rocking back and forth and inflating his white throat, he would try to seduce her. But the courtship ritual appeared only to bore the female, who flew away without acknowledgment or fanfare. Not to be denied, the male nighthawk pursued her, back into the lights of Baker Tower, calling incessantly, peent,peent, peent. The entire performance was repeated more than a dozen times, and eventually ended, either that night or a few days later, in copulation on Kiewit. Once their bond had solidified, the female would lay two eggs on the roof and begin incubation, and her mate, fresh from his nuptial triumph, would continue diving and booming until the eggs hatched.

Nighthawks are not always gravel-roof nesters. They nest, on occasion, in gardens, on bare patches in the middle of meadows, and in areas recently burned. I once heard them calling in northeastern Maine, above the spires of spruce and fir north of Lubec. A forest fire had cleared a tract of land in the Moose Horn National Wildlife Refuge, and nighthawks had found the site. I have discovered nighthawk eggs in the cobbles of west Texas and watched the birds coursing above South Dakota shortgrass, where they nested in bison wallows. Along the wooded Connecticut Valley, however, I found them in town, on rooftops, raining their nasal notes down on urban landscapes.

Nighthawks belong to the family of birds called nightjars or Caprimulgids, which consists of 67 species distributed across the globe; eight species are found in North America. Although they superficially resemble a whippoorwill (another Caprimulgid), nighthawks can be separated from other members of the family by their long pointed wings and lack of rictal bristles around the mouth. The name nighthawk is the standard English name for three species of Caprimulgids in the genus Chordeiles. The common nighthawk, circling Baker Tower, nests from southern Yukon east to Newfoundland and south through north-central Mexico.

I used to walk across the Green every spring in the middle of May to see if the nighthawks had returned from the Neotropics. I looked forward to our meetings, the annual homecoming. If the evening was cool, few flying insects loitered around the floodlights, and certainly no nighthawks, which are drawn to the light out of crepuscular skies. By June, though, the season would have ripened, the nighthawks arrived.

One evening I decided to meet the nighthawks on their own terms, high above the Dartmouth campus in the crown of Baker Tower. The sky darkened as the hands on the clock moved to the eight and the twelve. I braced myself for the bell, for the crush of sound, my back against the tower, my feet wedged in the white railing, every muscle in my body tight, as though waiting for an injection. Then the bell rang. And rang. And rang...but the sound was not nearly as crippling as I'd expected the blare, in fact, seems louder when heard from below, say at mid-Green, having somehow gathered perspective as it races toward town. Neither the nighthawks nor I flinched.

Later in the evening, a sudden drop in temperature scattered the birds, forcing them to forage closer to the ground, away from the tower. I heard peents out of the blackness. I imagined they swept above the tree tops, their mouths wide, swallowing insects. Once I thought a bird was headed for my perch, its voice close, over Rollins Chapel. I strained the night with my binoculars and found nothing. Peent,peent, and peent again, the voice faded away from campus, away from Hanover.

That was then. Now, whenever I cross the Green on a spring evening, I still look north, hoping to see amorous male nighthawks rising and diving against the incandescence of the Baker Library tower. Sadly, I have been disappointed. Nighthawks abandoned their nest sites on the gravel roofs of Kiewit and the old hospital four years ago and have vanished from the summer skies of downtown

Hanover. Spring nights have lost an expression and a visual feast. I have lost more: an old friend has gone away.

Ted Levin is a naturalist and writer living inVermont.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

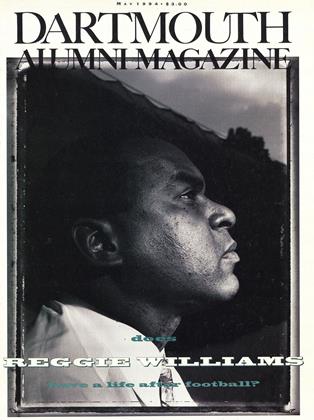

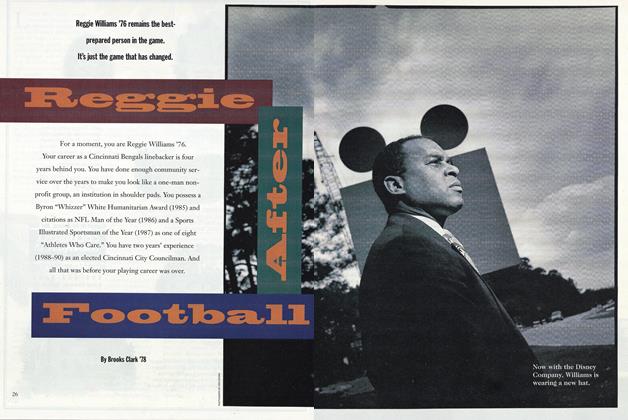

Cover StoryReggie After Football

May 1994 By Brooks Clark '78 -

Feature

FeatureCOOL STUDIES

May 1994 By KAI SINGER 95 -

Article

ArticleDr. Wheelock's Journal

May 1994 By "E. Wheelock" -

Article

ArticleWhy the Novel Matters

May 1994 By Karen Endicott -

Class Notes

Class Notes1975

May 1994 By W. Blake Winchell -

Article

ArticleWorries of a President

May 1994 By James O. Freedman

Ted Levin

Features

-

Feature

FeatureME Candidate

MARCH 1967 -

Feature

FeatureParadise Lost or Paradise Regained?

December 1978 -

Feature

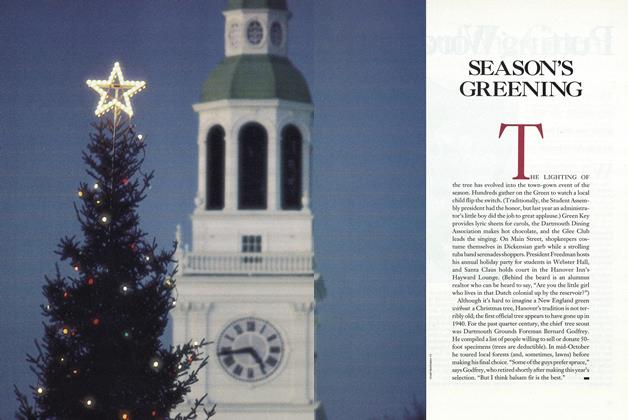

FeatureSEASON'S GREENING

December 1989 -

Feature

FeatureBIG JUMP

Winter 1993 By David Bradley ’38 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe Innovative Economist

JANUARY | FEBRUARY 2021 By MIKE SWIFT -

Cover Story

Cover StoryVoices Crying In The Wilderness

JUNE 1990 By The Editors