Nocturnal Jubilee

A naturalist tunes into voices crying out from the wilderness of the Second College Grant.

July/August 2005 Ted LevinA naturalist tunes into voices crying out from the wilderness of the Second College Grant.

July/August 2005 Ted LevinA naturalist tunes into voices crying out from the wilderness of the Second College Grant.

I AM A NATURALIST WHO HAS LIVED in the glow of Dartmouth College since 1977.1 arrived in the Upper Valley fresh from graduate school and eager to begin Work for a fledgling public science museum, the Montshire, which had evolved out of Dartmouth's own natural history collection, previously housed in Wilson Hall. During the 1980s I led numerous trips for the Montshire, including a three-day winter outing to the Second College Grant. Since that trip I had wanted to return in summer, when the green hills rock to the urgency of birds and frogs.

When I was a boy I went to summer camp on Lake Wen tworth in New Hampshire, where my mailing address, East Wolfeboro, suggested something vastly more remote than my home on Long Island. Camp bunks were named for features of the New Hampshire landscape- Ossipee, Pemigewasset, Saco, Chocorua, Kearsarge and so on. For two summers I stayed in the Umbagog bunk, though at the time I had no idea it was named for a wild, shallow lake that straddled the New Hampshire-Maine border, just south of the Second College Grant, which I also hadn't heard of.

Last June I finally visited the Grant again, where I was reminded of those bygone days at summer camp, when, for the first time, I had faced a landscape that seemed to extend to the very edge of the earth. I had that same expansive feeling as soon as I unlocked the main gate: I was surrounded by what Anne Morrow Lindbergh called the "green silence of wilderness": the swirl of wind, the purl of the river, the smell of evergreens, the amorous crooning of songbirds. The industry of mosquitoes.

After unpacking the van, just after noon, and settling into the Gate House for the weekend, my wife, Annie, and I sent our two boys upriver on a quest for moose (or, more likely, mergansers). The two of us walked the Dead Diamond Road, stretching our legs from three hours of driving, noting birds and their songs: parula warblers, redstarts, chestnut-sided warblers and olive-sided Flycatchers who sounded as though they were bellying up to the bar—quick, threebeers, quick, three beers. A broad-winged hawk circled above the Gorge Lookout, the white bands of its splayed tail glowing in the sunlight.

The rock face of the Diamond Peaks, which hosted nesting golden eagles as recently as 1962, stood hard against the northern skyline, a monument to raw forces that once convened across the Northeast. A hundred years ago I might have eavesdropped on gossiping wolves as their disembodied voices rose from the Peaks. Thus far, the 21st century belongs to eastern coyotes, whose high-pitched falsetto reminds me that nature abhors a void. Mountain lions, called catamounts in New England, no longer roam the Grant, but bobcats still do. Woodland caribou no longer wander down from Quebec, but moose have staged a comeback. Black bear never left. And, after a lengthy absence, perhaps as far back as the days of the last wolf, the sleek, arboreal pine marten—known as sable to furriers—has returned to hunt squirrels along the spindly limbs of the forest canopy. (One tore apart the porch of Gate Camp this last spring.)

At the management center we turned down the Swift Diamond Road. A mile or so beyond the junction, a bear rushed out of a thicket and then disappeared into the spruce and fir. Our sighting lasted just a nanosecond; the big and brown mammal kept low to the ground, lumbering but quick, and silent as smoke. For at least an hour we couldn't seem to think or talk about anything else. Even the snowshoe hare grazing along the shoulders of the road couldn't take our thoughts off the bear. Awoodland jumping mouse bounded by, and, like the bear, vanished in a moment. Jumping mice are deep-woods rodents, true hibernators (like woodchucks and bears) that rarely enter the domain of humans.

We returned to Gate Camp to discover that our boys had found a moose femur in the Dead Diamond—broken, river-smooth and green with algae. While we handled the bone a female common merganser flew downstream, an arrow of a duck, wings whirring with a stiff, mechanical efficiency.

At dusk we packed the boys in the van and cruised the Dead Diamond Road, windows open, listening to the voices of the night. The amphibian cacophony made me realize that the Grant is a mosaic of wetlands—vernal pools, marshes, swamps, peat lands, seeps, springs—that bind the Magalloway, the Dead Diamond, the Swift Diamond and all their tributaries into a fertile aqueous whole, and that the hills and peaks were merely islands in a sea of waterlogged earth. The din of frogs was everywhere; peepers mostly, spiced by the sweet trill of American toads and twang of green frogs.

At Osprey Marsh, somewhere beyond our range of vision, a snipe performed his courtship flight; the twitter of tail feathers, a counterpoint to the frog chorus, as the bird fluttered unseen in the gathering darkness. Equally hidden but much closer to the road, an American bittern called from a weft of reeds: oonk-a-lunk, oonk-a-lunk, a hollow, directionless sound as though the marsh itself was speaking.

Farther down the road, beyond the management center, the garble of peepers and the occasional voice of a toad rose from innumerable pools in dark, seemingly unbroken woods. The pools, catch basins for spring rain and snow melt, overflow in June and dry out in August, unless a tropical storm moves inland or a run of heavy thunderstorms water the earth. If, as novelist Hal Borland wrote, 'A dozen peepers make less than a human handful, but their voice can fill a whole evening," we had to have been parked amid a hundred dozen, perhaps a thousand dozen. We had to scream to be heard.

A mile or so beyond the ardent frogs, still well south of the Merrill Brook Cabin, I stopped the van and listened. The faint hooting of love-struck barred owls—who-cooks-for-you, who-cooks-for-you-all—rolled out of the distance. I had to strain to hear them above the frogs, above the wind and the river. Like the frogs, the owls must have had a lot on their minds, or at least a rush of hormones. Their calls were methodical and ceaseless, spaced just far enough apart for the meaning to sink in. Eventually, another pair answered the first. Living echoes.

The snipe, the bittern, the frogs, the owls—all were all part of the unseen parade of life that turned the Second College Grant into a nocturnal jubilee, and took me back to those days of discovery at summer camp on Lake Wentworth, when the world seemed infinitely larger and full of mystery.

TED LEVIN lives in Thetford, Vermont.His book Liquid Land won the 2004 JohnBurroughs Award for natural history writing.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

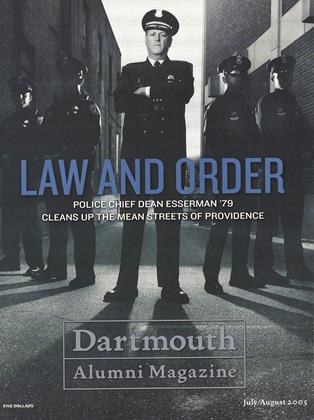

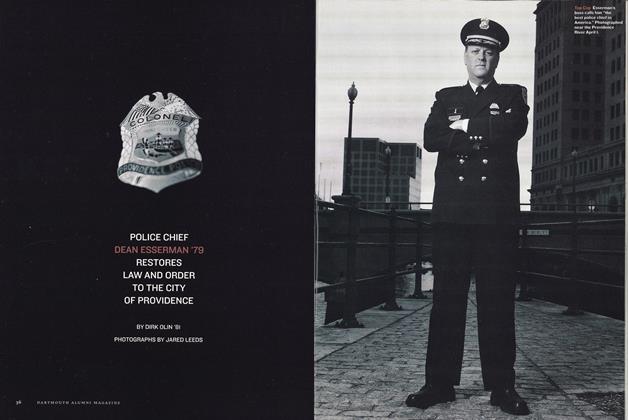

Cover StoryPolice Chief Dean Esserman ’79 Restores Law and Order to the City of Providence

July | August 2005 By DIRK OLIN ’81 -

Feature

FeatureMud, Madras and Madness!

July | August 2005 By Gina Barreca ’79 -

Feature

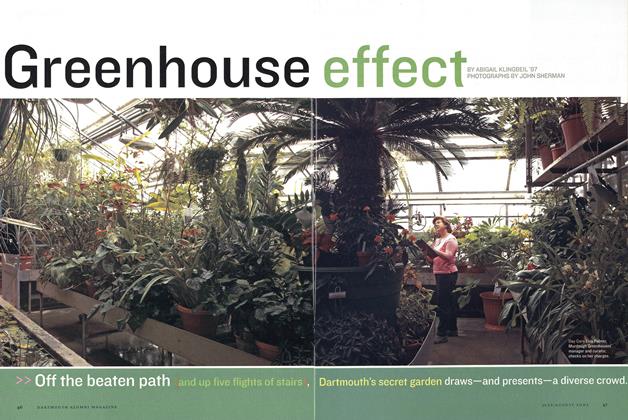

FeatureGreenhouse Effect

July | August 2005 By ABIGAIL KLINGBEIL ’97 -

Feature

FeatureNotebook

July | August 2005 By JOHN SHERMAN -

Feature

FeatureAlumni News

July | August 2005 By Thomas Vieth '80 -

FACULTY

FACULTYLearning Curve

July | August 2005 By James Heffernan

Ted Levin

OUTSIDE

-

OUTSIDE

OUTSIDEClimb Every Mountain

JANUARY | FEBRUARY 2016 By BRANDON DEL POZO ’96 -

OUTSIDE

OUTSIDEHarvard Leads the Way

Jan/Feb 2005 By Bryant Urstadt '91 -

OUTSIDE

OUTSIDESea Change

Jan/Feb 2009 By David McKay Wilson -

OUTSIDE

OUTSIDEThe Skipper

July/Aug 2009 By Sarah Tuff -

OUTSIDE

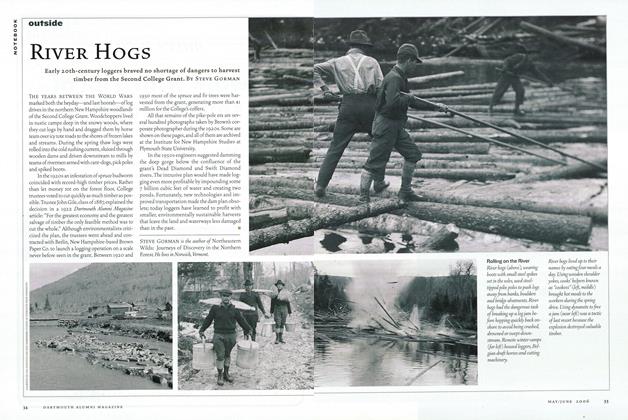

OUTSIDERiver Hogs

May/June 2006 By STEVE GORMAN -

OUTSIDE

OUTSIDENordic Exposure

JANUARY | FEBRUARY 2023 By Svati Kirsten Narula ’13