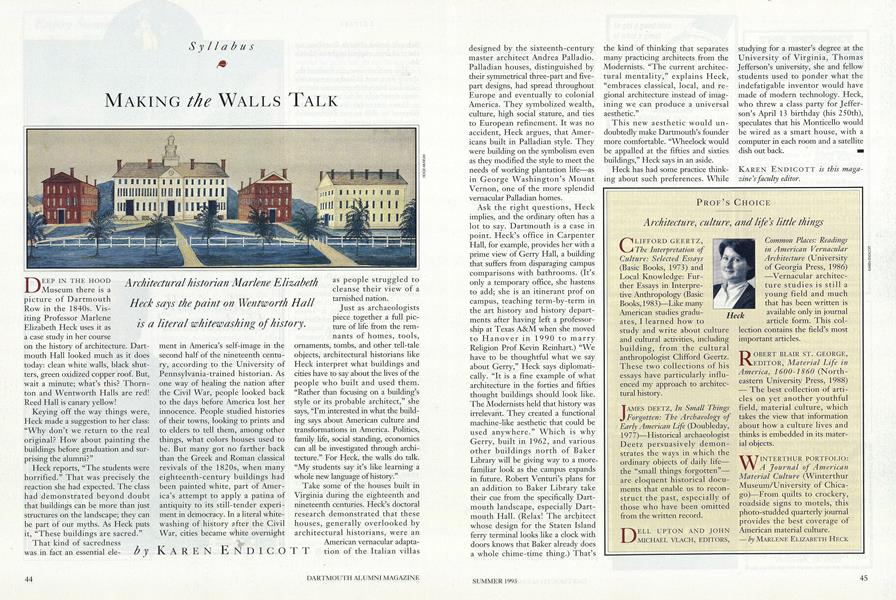

Deep in the hood Museum there is a picture of Dartmouth Row in the 1840s. Visiting Professor Marlene Elizabeth Heck uses it as a case study in her course on the history of architecture. Dartmouth Hall looked much as it does today: clean white walls, black shutters, green oxidized copper roof. But, wait a minute; what's this? Thornton and Wentworth Halls are red! Reed Hall is canary yellow!

Keying off the way things were, Heck made a suggestion to her class: "Why don't we return to the real original? How about painting the buildings before graduation and surprising the alumni?"

Heck reports, "The students were horrified." That was precisely the reaction she had expected. The class had demonstrated beyond doubt that buildings can be more than just structures on the landscape; they can be part of our myths. As Heck puts it, "These buildings are sacred."

That kind of sacredness was in fact an essential element in America's self-image in the second half of the nineteenth century, according to the University of Pennsylvania-trained historian. As one way of healing the nation after the Civil War, people looked back to the days before America lost her innocence. People studied histories of their towns, looking to prints and to elders to tell them, among other things, what colors houses used to be. But many got no farther back than the Greek and Roman classical revivals of the 1820s, when many eighteenth-century buildings had been painted white, part of America's attempt to apply a patina of antiquity to its still-tender experiment in democracy. In a literal whitewashing of history after the Civil War, cities became white overnight as people struggled to cleanse their view of a tarnished nation.

Just as archaeologists piece together a fall picture of life from the remnants of homes, tools, ornaments, tombs, and other tell-tale objects, architectural historians like Heck interpret what buildings and cities have to say about the lives of the people who built and used them. "Rather than focusing on a building's style or its probable architect," she says, "I'm interested in what the building says about American culture and transformations in America. Politics, family life, social standing, economics can all be investigated through architecture." For Heck the walls do talk. "My students say it's like learning a whole new language of history."

Take some of the houses built in Virginia during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Heck's doctoral research demonstrated that these houses, generally overlooked by architectural historians, were an American vernacular adaptation of the Italian villas designed by the sixteenth-century master architect Andrea Palladio. Palladian houses, distinguished by their symmetrical three-part and fivepart designs, had spread throughout Europe and eventually to colonial America. They symbolized wealth, culture, high social stature, and ties to European refinement. It was no accident, Heck argues, that Americans built in Palladian style. They were building on the symbolism even as they modified the style to meet the needs of working plantation life as in George Washington's Mount Vernon, one of the more splendid vernacular Palladian homes.

Ask the right questions, Heck implies, and the ordinary often has a lot to say. Dartmouth is a case in point. Heck's office in Carpenter Hall, for example, provides her with a prime view of Gerry Hall, a building that suffers from disparaging campus comparisons with bathrooms. (It's only a temporary office, she hastens to add; she is an itinerant prof on campus, teaching term-by-term in the art history and history departments after having left a professorship at Texas A&M when she moved to Hanover in 1990 to marry Religion Prof Kevin Reinhart.) "We have to be thoughtful what we say about Gerry," Heck says diplomatically. "It is a fine example of what architecture in the forties and fifties thought buildings should look like. The Modernists held that history was irrelevant. They created a functional machine-like aesthetic that could be used anywhere." Which is why Gerry, built in 1962, and various other buildings north of Baker Library will be giving way to a more, familiar look as the campus expands in future. Robert Venturi's plans for an addition to Baker Library take their cue from the specifically Dartmouth landscape, especially Dartmouth Hall. (Relax! The architect whose design for the Staten Island ferry terminal looks like a clock with doors knows that Baker already does a whole chime-time thing.) That's the kind of thinking that separates many practicing architects from the Modernists. "The current architectural mentality," explains Heck, "embraces classical, local, and regional architecture instead of imagining we can produce a universal aesthetic."

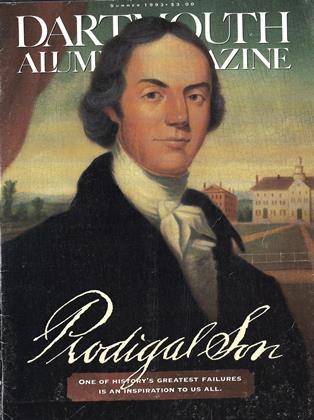

This new aesthetic would undoubtedly make Dartmouth's founder more comfortable. "Wheelock would be appalled at the fifties and sixties buildings," Heck says in an aside.

Heck has had some practice thinking about such preferences. While studying for a master's degree at the University of Virginia, Thomas Jefferson's university, she and fellow students used to ponder what the indefatigable inventor would have made of modern technology. Heck, who threw a class party for Jefferson's April 13 birthday (his 250 th), speculates that his Monticello would be wired as a smart house, with a computer in each room and a satellite dish out back.

A rchitectural historian Marlene Elizabeth Heck says the paint on Wentworth Hall is a literal whitewashing of history.

Karen Endicott is this magazine faculty editor.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryThis Man Scanndalized Eleazar Wheelock

June 1993 By Jerold Wikoff -

Feature

FeatureTHE PEMI AFFAIR

June 1993 By KIRK SIEGEL'82 -

Feature

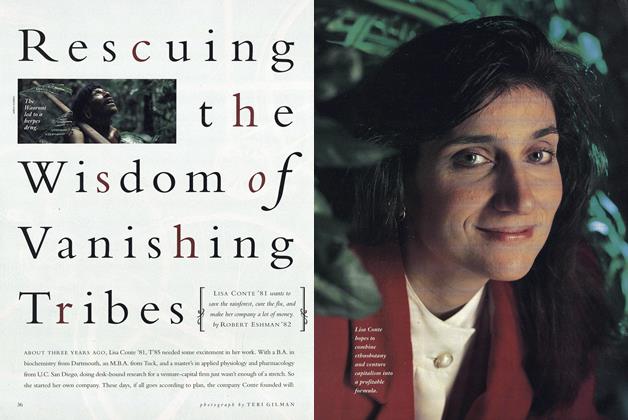

FeatureRescuing the Wisdom of Vanishing Tribes

June 1993 By Robert Eshman '82 -

Feature

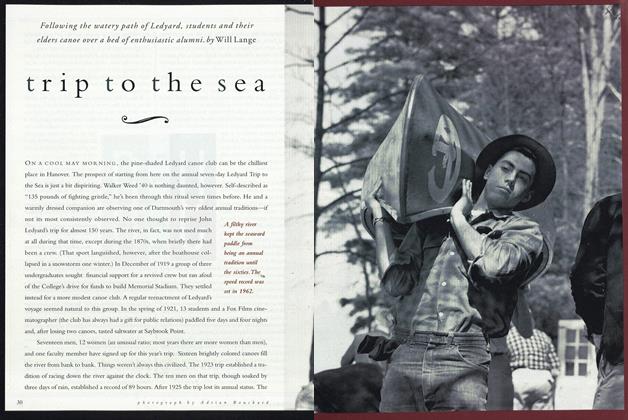

FeatureTrip to the sea

June 1993 By Will Lange -

Feature

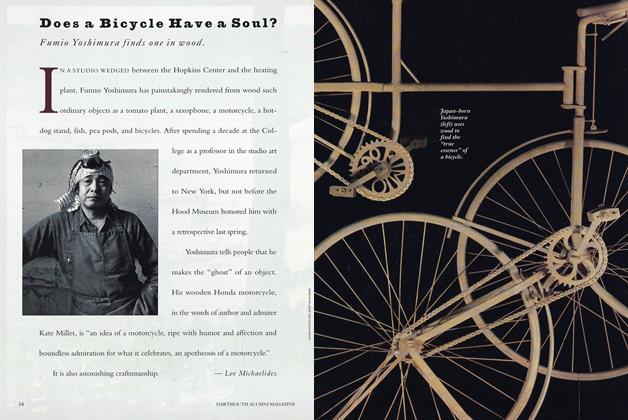

FeatureDoes a Bicycle Have a Soul?

June 1993 By Lee Michaelides -

Article

ArticleDr. Wheelock's Journal

June 1993 By "E. Wheelock"

Karen Endicott

-

Article

ArticleJoining the Queue

May 1993 By Karen Endicott -

Article

ArticleSlesnick by the Numbers

SEPTEMBER 1994 By Karen Endicott -

Article

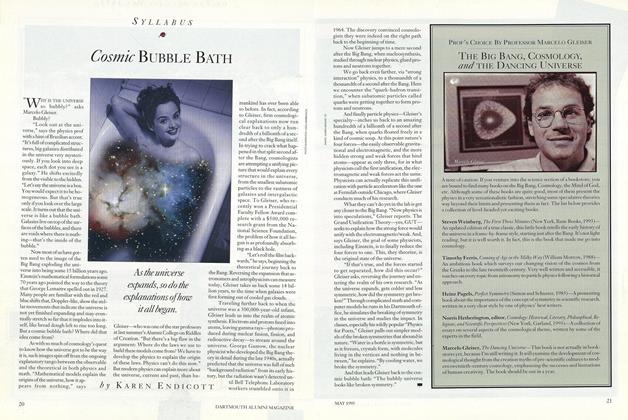

ArticleCosmic Bubble Bath

May 1995 By Karen Endicott -

Article

ArticleHISTORY THAT WON'T FLY

May 1995 By Karen Endicott -

Article

ArticleCopper Crown

October 1995 By Karen Endicott -

Interview

Interview"A Diversity of Ideas"

July/Aug 2003 By Karen Endicott