Art excerpt from They Used to Call Me Snow White... But I Drifted (Viking and Penguin)

When I started my first year as a student at Dartmouth College, there were five men for even' woman. 1 thought I had it made. Dartmouth had only recently admitted women, and the administration thought it best to get die alumni accustomed to the idea by sneaking us in a few at a time. With such terrific odds in my favor socially, how could I lose? I'd dated in high school and although I wasn't exactly Miss Budweiser I figured I'd have no problem getting a date every Saturday night. But I noticed an unnerving pattern. I'd meet a cute guy at a party and talk for a while. We would then be interrupted by some buddy of his who would drag him off to another room to watch a friend of theirs "power boot" (the local vernacular for "projectile vomiting'") and I realized diat the social situa- tion was not what I had expected.

Then somebody explained to me that on this campus "they think you're a faggot if you like women more than beer." This statement indicated by its very vocabulary die advanced nature of the sentiment behind it. It a guy said he wanted to spend the weekend with his girlfriend. for example, he'd be taunted by his pals who would veil in beery bass voices "Whatsa matter with you, Skip? We're gonna get plowed, absolutely blind this weekend, then we're all gonna power-boot. And you wanna see that broad again? Whaddayou, a faggot or something?"

It turned out the male-female ratio did not prove to be the marvelous bonus 1 had anticipated. But still I figured that the school was good enough to justify- spending the next four years getting down to studying and foregoing a wild social life. I thought it would all work out, diat at least I would be accepted in my classes as a good student and get through the next couple of years without too much worry or trouble. Okay, 1 told myself, I could live with that, and found in fact dating guys from other schools to be a healthy practice anyway.

But the real shock came in the classroom where I was often one of two or three women in the group. One professor, I remember, always prefaced calling on me or any other woman in the class by asking, "Aliss Barreca, as a woman, what is your reading of the text?" I was profoundly embarrassed to be asked my opinion as a woman, since it seemed somehow less authoritative than being asked my opinion as a student or as a "general' reader. At first, I jokingly replied that I would be happy to answer '"as a person," but that it was hard for me to answer as a woman. When die professor didn't so much as smile, I knew that tactic wouldn't work. Every time I raised my hand to answer a question, I was asked my opinion as a woman. It frustrated and angered me, because I wanted to be treated as an individual and not as a representative of a group. It took months to understand that in the eyes of this teacher, I'd always be a "Miss" rather than just another, ordinary student. When I realized that there was no alternative, I figured I'd go with it, exaggerate the situation enough so diat I could at least enjoy myself. So I started prefacing every answer with the phrase, "'As a woman, I think Shakespeare means...," "As a woman, it strikes me that Tennyson's point i5..." But then I figured, why stop at this? I started to say "As a woman, I think the weather's rather cold for June." "As a woman, I think I'll have die meatloaf for dinner." "As a woman, I think I'll go to bed early tonight." It started out as a joke, but as it caught on (a number of my friends started to use the same strategy to make the professors and guys in general hear how their remarks sounded) we started to examine further. Maybe we really were always speaking as a woman. Maybe there was just no such thing as speaking as "just" a person. Maybe we always spoke as women whenever we spoke. Maybe this joke wasn't such a joke.

So chat even as I stopped saying, "As a woman, I believe such-and-such," I started thinking it. It occurred to me that nothing was neuter or neutral. I saw that my responses were in part determined by the tact of my gender as well as by other factors like my class and ethnicity. I didn't read novels about war in the same way a man would, for example, since I hadn't been brought up to consider going to war as a soldier as a possible future for myself. I hadn't played war games as a kid, I didn't find die idea of war engaging. It did not have "universal appeal" since it didn't appeal to me, a narcissistic but neveitheless compelling argument. In the same way that die male students complained that Jane Austen was obviously a second-rate writer because all she was interested in was. marriage (Mark Twain once said that it was "a pity they let her die a natural death"), so I decided to assert that Hemingway's concern for bullfighting was no concern for an intelligent. insightful woman. Of what interest is bullfighting to the contemporary female reader? Hemingway was therefore secondrate, by their definition, since his subject matter had limited appeal and seemed gender-specific. I learned to answer "Of course" when asked whether I responded to things as a female.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

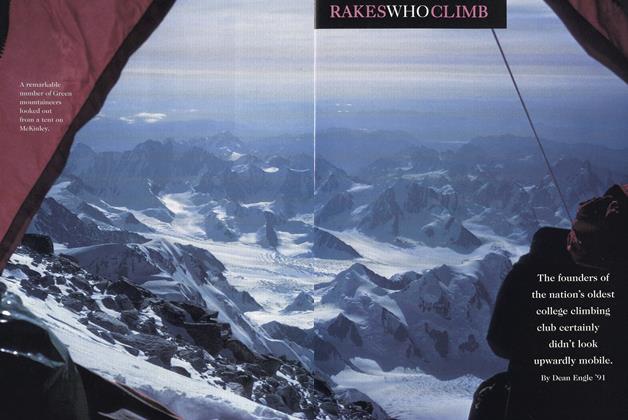

FeatureRAKES WHO CLIMB

February 1994 By Deab Engle '91 -

Feature

FeatureTau Iota Tau and Other Brassy Memories

February 1994 By Regina Barreca '79 -

Cover Story

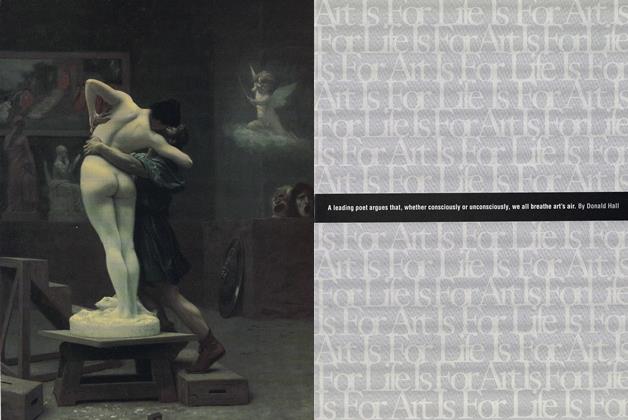

Cover StoryA leading poet argues that, whether consciously or unconsciously, we all breathe art's air.

February 1994 By Donald Hall -

Feature

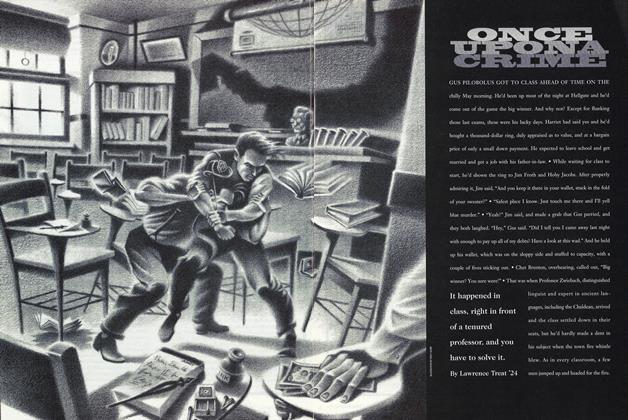

FeatureONCE UPON A CRIME

February 1994 By Lawrence Treat '24 -

Feature

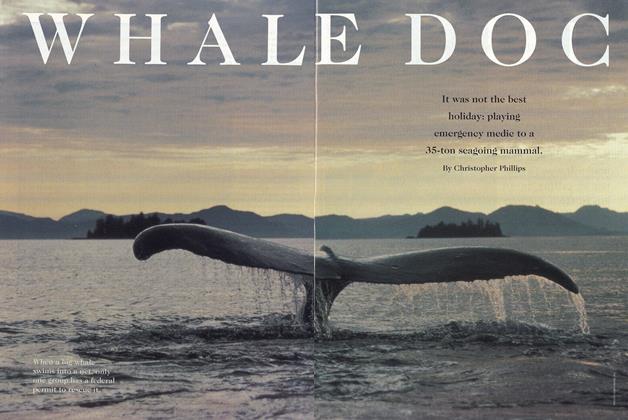

FeatureWHALE DOG

February 1994 By Christopher Phillips -

Article

ArticleDr. WHEELOCK'S JOURNAL

February 1994 By "E. Wheelock"