The founders of the nation's oldest

n the mid-thirties, no college looked as much like a traditional all-male college as Dartmouth did: Sanborn tea each afternoon at four, fraternity singing competitions in white flannels and green jackets, sleigh rides with dates at Winter Carnival. Gentlemen gathered in their cherished organizations: the Press Club, Trap & Skeet, and the Daniel Oliver Associates, a group that devoted itself to the love of rare books.

Then there was another set entirely. In a back room of the squat and stone-sided Robinson Hall, an odd assortment of students gathered several times a year. Wearing dirty knickers, T-shirts, and gaudy headbands, and as devoted to cigarettes or fifths of Jack Daniels as they were to pitons and butterfly knots, they represented the other side of Dartmouth. They were rogues; their purpose was simply, noisily, and chaotically "To Climb," and they started the nation's oldest college climbing school. They were the Dartmouth Mountaineering Club, and Jack Durrance '39 was their messiah.

Strikingly handsome with a shock of black hair, Durrance was a whooping and hollering wildman, a yodeler and beer quaffer. Fresh from Munich, he had learned to climb with Germany's best young rock technicians in the Bayerische Alps. "He was a bad ass, a rake, a smoker everything a DMC member aspired to be," said Barry Corbet '58.

As to founding the DMC, Durrance wanted to do anything but. He had no time for organization. When someone suggested in the fall of 1936 that he start a climbing club, he answered: "Why the hell should I?" But without any other skilled climbers at Dartmouth, he was partnerless. "I didn't have any money," he recalled later, "and I wanted to climb in the Tetons, so I taught some Dartmouth men to climb. They saw to it that I didn't starve and I saw to it that they didn't fall off the mountain." That was the way Dartmouth's rowdiest club was haphazardly roped together.

WHEN DURRANCE GRADUATED FROM THE College, scores of faces, ridges, and buttresses were still unclimbed in the Tetons most notably the West Face of the Grand, the most difficult alpine climbing in North America at the time.

At 3:30 on an August morning in 1940, under a dark, cloudy sky, Hank Coulter '43 and Jack Durrance started up the face. By midday they were within 1,000 feet of the summit, with a series of difficult, rotten chimneys above. It was at the base of one of these that the two almost abandoned their climb. The chimney had a cascade of water running down its entire length with no hope for a piton for 100 feet. Durrance made his way partway up, but his feet slipped and he turned back. He glanced down. Coulter was asleep on the ledge. Durrance cussed Coulter out and decided to try the face once more. The two stashed all their gear except rope, pitons, and camera; they left Coulter's pack on a ledge. Traversing left, Durrance avoided the cascade, climbed through an overhang, and then back right on a smooth slab into a corner. Packless, Coulter was still hard-pressed to second the pitch. Just as night fell, the two reached the summit.

AFTER A BRIEF RESPITE FOR WORLD WAR II, climbing took off once again at Dartmouth: Coulter and Merrill McLane '42 rejuvenated the climbing school that Durrance had started and wrote a guidebook to the Tetons; Walter Prager, a Swiss skier, mountain guide, and Dartmouth ski coach, lent his expertise to the club; and summers meant going off to the Tetons and the Wind Rivers. But it wasn't until the fifties that Dartmouth climbing regained its pre-war high. With the revival came risk: In 1954, Les Viereck '51 was with a four-person party that fell 1,000 feet down a ridge after traversing Mt. McKinley. One member was killed, another was immobilized with a broken pelvis, and Viereck and another climber hiked out for four days to get help.

One of the fifties' best climbers was Barry Corbet. Darkhaired and muscular, Corbet was reserved: a brilliant and witty but introverted young man. Corbet simply didn't know what to say or do with women. So, he created a mental training regimen. If you didn't look at women, think about women, or have anything to do with women for three weeks straight, then you could live totally unfazed by women for the rest of your life. It was the Corbet Control System. One day, though, it failed.

In the summer of 1959, after he realized that bivouacs were more thrilling in the Tetons than they were outside his dorm room at Dartmouth he dropped out his junior year Corbet camped at Jenny Lake, looking for a partner. The only person there was Muffy French, whose brother, Bob '58, was a climber at Dartmouth and a friend of Corbet's. Bob had known that Corbet had a weakness for redheads Corbet hadn't yet succumbed and so had invited his sister out to climb in Jackson. Muffy was eager to climb. When she saw Corbet, she said, "Come on, Barry. Let's go climb the Southeast Face of Symmetry Spire." Corbet had no choice. Muffy, a ski racer in college and the first woman to become certified as a National Ski Instructor, climbed the pants off him. When the two of them came down, Corbet was exhausted and collapsed in camp. Perhaps in consolation, Muffy gave him a back rub. And that was the end of the Corbet Control System.

Some say he should have stuck to his regimen. He and Muffy were married, divorced, then remarried and redivorced. During those years, just after he had purchased his own guiding concession in the Tetons, Corbet crashed in a helicopter while filming a skiing movie near Aspen, and was left paralyzed from the waist down. His climbing career shattered, he took up kayaking and became a whitewater racer. Since then, he has produced hundreds of films about, and for, physically disabled people.

If Dartmouth climbers flourished in the fifties, they paid for their exploits in the sixties. On die first American Everest expedition in 1963, Jake Breitenbach '57 was killed when a huge block of ice collapsed on top of him. Five years later, David Koop '69, son of Surgeon-General-to-be C. Everett Koop '37, was killed in a fall on Cannon Mountain. Almost a year later to the day, David Seidman '6B was killed on a fateful 1969 Dhaulagiri expedition during which an avalanche claimed the lives of seven men.

Despite these accidents, the sixties were the Mountaineering Club's most impressive years. Of the 19 Western climbers on a 1963 Everest expedition, five had spent formative years at Dartmouth. Barry Prather '61 had been a survey leader on the first ascent of Mount Kennedy in 1965; Dave Dingman '58 had led the 1958 McKinley expedition and was a medical officer on Everest; Jake Breitenbach and Barry Corbet had followed Dingman a year later on McKinley and pioneered a handful of routes in the Tetons; Barry Bishop '53 was one of the first to climb McKinley's West Buttress in 1951. In preparation for Everest, Bishop had joined Sir Edmund Hillary's Himalayan expedition in 1960. Working for National Geographic in 1963, Bishop was one of four men to summit Everest via the South Col.

The summer of 1968 saw one of the Mountaineering Club's greatest individual achievements. Dave Seidman, who was back from the Direct South Face of McKinley, and Todd Thompson were two of the best young mountaineers in America. They wanted to climb in Alaska that summer but had no idea what mountain or what route. It wasn't until they visited Bradford Washburn at the Boston Museum of Science that they decided on their route. On Washburn's office wall was a huge print of Mt. Kennedy's North Ridge. Three parties had tried the route before; each had turned back after only a few hundred feet. Perfect, they decided.

Two people weren't enough. They turned their attention to a young sophomore, Phil Koch '70. At the age of 19, he was one of the most solid and consistent climbers on campus. "Dave and Todd came by one night to my dorm room," Koch says about his introduction to Kennedy, "and we talked about various things. Finally, they got down to business and asked, 'Would you like to come to Kennedy with us this summer?"'

Koch was astonished. He recalled years later: "It would be like Bill Clinton showing up and saying, 'Look, I really need a secretary of state.'" Koch was so caught up in the idea of climbing a new route on a big mountain that he didn't realize the magnitude of what he was signing up for. On the entire 6,000 vertical feet of Kennedy's North Ridge not one ledge was more than a foot wide. The climbers had to chop platforms out of the ice for all three camps. Camp II, which they called the Crystal Palace, took ten hours to chop out. "Things were cold and airy up there," wrote Koch in the 1969 Dartmouth Mountaineering Journal. "Objects dropped out the tent door traveled in unarrested flight nearly 4,000 feet back down to the glacier."

Above was the crux, a 600-foot gash in bare rock above an icefield. Seidman and Thompson hammered pitons and aided their way up a strenuous, awkwardly flaring chimney to the hanging glacier above. Deep snow and a final camp allowed them a summit bid the following day. It took 25 days and more than 5,000 feet of rope to reach the summit and another nine days to descend. It was, many climbers agreed, the most difficult expedition ascent in North America.

THE EARLY SEVENTIES, STILL IN THE SOMBER shadow of Vietnam, were the New England years for the Mountaineering Club. Cannon Mountain, Cathedral and Whitehorse, Owl's Head, and the local New Hampshire crags grew in popularity. Forty years after the club was born, Andy Tuthill '78 matriculated at Dartmouth. A New England boy who learned to climb from Bob Bates at Exeter, Tuthill was a climber in the Durrance tradition: he climbed to get rid of a hangover, then drank to celebrate the climb. He sported a mop of frizzy blond hair, played a mean banjo, and regularly soloed routes on Cannon Mountain. Within a few months he had taken over the leadership of the club, and whatever semblance of order once existed was erased completely. "Meetings were a circus act," remembered one climber. "At meetings," Tuthill says, "we'd get the business stuff over with real quick. Then we'd drag in a case or two of beer and a slide projector, and some fool would throw in some slides and all the rest of us would just point and make fun of him."

John Cleary '74 was Dartmouth's vulgarian at the time. Scraggy and shameless, he had the nickname of Dr. Disgusto. In the summer of 1973, Cleary was one of six Dartmouth men on the unclimbed Southeast Ridge of Mount Hunter. Two weeks into the expedition, high on a heavily serraced ridge, their food supply started running low and they rationed everything, including the sardines in tomato sauce. "We were so hungry, we'd eat anything," remembered Chris Walker '73. Anything, that was, until Cleary took a poke at it. Just as someone was opening the sardines, he would lean over and sniff at the can, then give such a vivid and lewd description of the sauce unprintable in this respectable magazine that everyone else reeled in disgust. When Cleary was around, the men on Hunter never had a healthy appetite, no matter how hungry they were.

WHEN MARK SONNENFELD 'BO arrived at Dartmouth in the fall of 1976, he unwittingly changed the focus of the Mountaineering Club. His first day at Dartmouth, the big-knuckled, blond freshman from Princeton, New Jersey, climbed a longstanding, overhanging boulder problem at the nearby Norwich Cliffs. "People had been trying this stupid little overhang for years," said Peter Kelemen '78. Kelemen spread the word: "This kid is good." What was remarkable about Sonnenfeld, though, was not so much that he was better than everyone else but that he paved the way to a new standard of rock climbing. He had no use for the mountains; he just wanted to rock climb. "As soon as Mark did daat overhang," recalls Kelemen, "I did it, and then pretty soon, we could do it six different ways and they weren't even hard." Unknowingly, Sonnenfeld had created a movement that would draw a handful of Dartmouth climbers to the fore of New England rock climbing. "I was at Harvard," says Bob Palais, a longtime high-school friend of Sonnenfeld's, "and I was always completely jealous of the DMC. Dartmouth was the model for hard-core rock climbing. All we had were mountain snobs."

One of Sonnenfeld's proteges, at five-foot-seven and 140 pounds, was Neil Cannon 'B2. He was a cocky and brash New Jersey boy who wanted to be the best, but "to get good at climbing," he claimed, "you had to do something other than just climb." Cannon trained: he lifted weights, bouldered endlessly on the campus buildings, and worked out with the ski team. In the next four years he set himself at the top echelons of New England climbing, including the first free ascent of Cannon Mountain's Labyrinth Wall Direct with Alison Osius. The route was called the longest and most continuously difficult free climb in New England.

Those years brought their calamities as well. The last day of 1980, Peter Friedman '83 fell to his death in Odell's Gully in Huntington Ravine, and his partner, Tor Raubenheimer '84, was badly injured. In the summer of 1983, sophomore Mike Woolley '85 was killed in Peru. He had-just returned from a successful climbing season in the Alps. When a trip to Peru's Cordillera Blanca took shape in 1983, he was an obvious choice. After two weeks, he and four other Dartmouth climbers had completed routes on half a dozen mountains. According to Dougald Mac Donald '82, leader of the trip, it was then that Woolley's ambition got the best of him. "He had a calculated recklessness," says Mac Donald, "and more than any of us, he was determined to make a name in the climbing world."

Woolley wanted to climb the Northeast Face of Huascaran Norte, a difficult route that had seen less than a dozen ascents. He and Randy Day 'B2 struggled up the rockfall-prone face, but after three miserable bivouacs above 20,000 feet decided to descend. On one of many traverses, Woolley slipped and fell, dragging Day with him. Hundreds of feet later, they came to rest. Woolley was unconscious in a pool of blood below a steep ice cliff; Day was spared the ice cliff and lay with a dislocated hip. After painfully lowering himself to his partner, Day made Woolley as comfortable as he could, but that night Woolley died. Three days later, Day cradled across the final snowfield to the west side of the mountain, onto the regular route, and was rescued.

After Ann Schonfield 'B5, a student in a climbing-school class, broke her leg during an outing to the Winslow Cliffs the year before Woolley died, the College cut off physical-education credit for rock-climbing classes, required instructors to submit climbing resumes, and almost shut down the climbing school. But with an unbridled demand for climbing instruction and a determination on the part of the club's leadership to keep the climbing school alive, it survived the turmoil.

The eighties saw four more climbing deaths: Ted Johnson '8O was killed in an avalanche on Mount Kitchner with Neil Cannon; Brian Dunleavy 'B9 fell 400 feet while soloing Willey's Slide in New Hampshire's Crawford Notch in November 1987; and in 1988, two Thayer students were killed near Wiessner's Buttress on Cannon Mountain when the block they were rappelling on fell away under their feet. Ten climbers in 25 years.

THE KLETTERSCHUHS AND KNICKERS of Dartmouth's old mountaineers are gone. So are the hemp ropes in musty closets and old mountaineering badges. The DMC no longer turns out world-class mountaineers and rock climbers. Today, few college clubs do. American climbing, and climbing around the world, is defined by individuals. But there are two things that are still

unique to the Dartmouth Mountaineering Club. The history of climbing at Dartmouth is one of the longest and richest of its kind. "College climbing was born at Dartmouth," said climber Glenn Exum. And as Neil Cannon was fond of saying, "Where else can you get out of class by ten and be halfway up Cannon Mountain by three?"

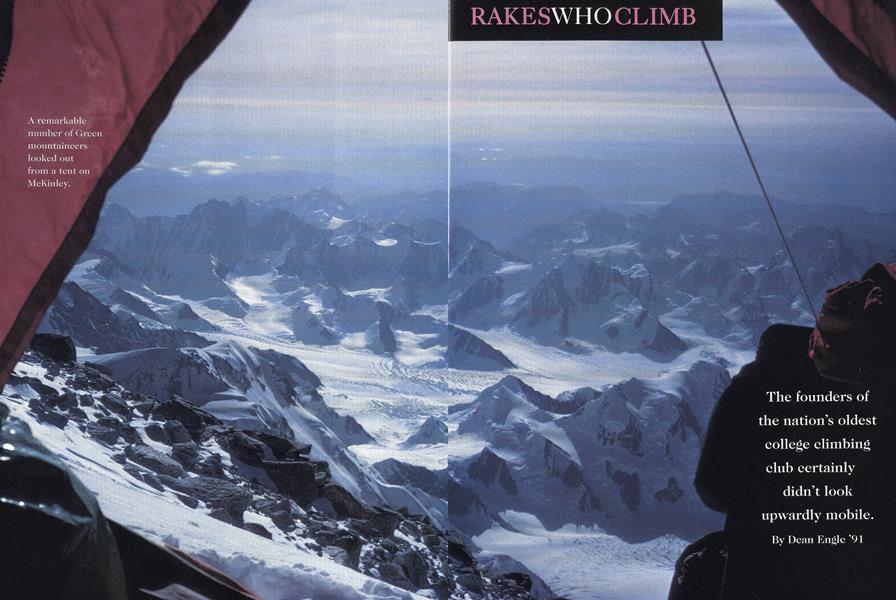

A remarkable number of Green mountaineers looked out from a tent on MeKinley.

Durrance and friends out West.

Holt's Ledge was popular in the seventies

George Billings '62 on Norwich cliffs.

On theentire6,000verticalfeet ofKennedy'sNorthRidgenot oneledgewasmorethan afootwide.

His feetslippedand heturnedback. Heglanceddown.Coulterwasasleepon theledge.

Within a fewmonthsTuthillhadtakenover theleadership ofthe club,andwhateversemblanceof orderonceexistedwaserasedcompletely.

Dean Engle has just completed a history of the Dartmouth MountaineeringClub; copies may be purchased by writing to the club in Hanover.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureTau Iota Tau and Other Brassy Memories

February 1994 By Regina Barreca '79 -

Cover Story

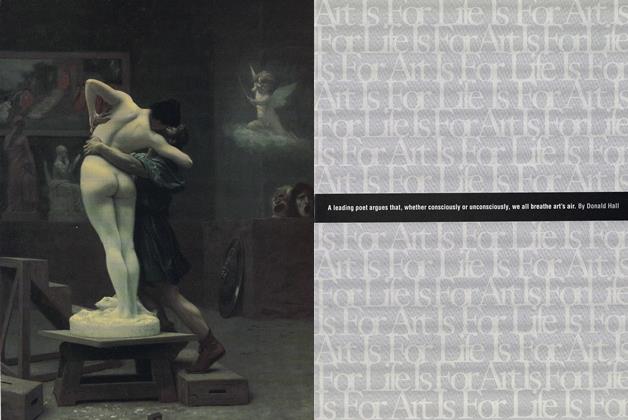

Cover StoryA leading poet argues that, whether consciously or unconsciously, we all breathe art's air.

February 1994 By Donald Hall -

Feature

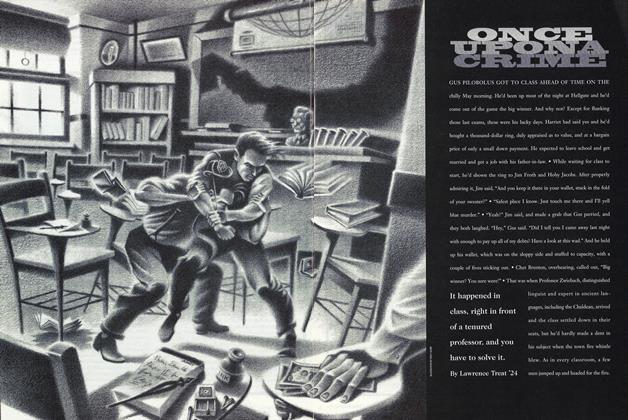

FeatureONCE UPON A CRIME

February 1994 By Lawrence Treat '24 -

Feature

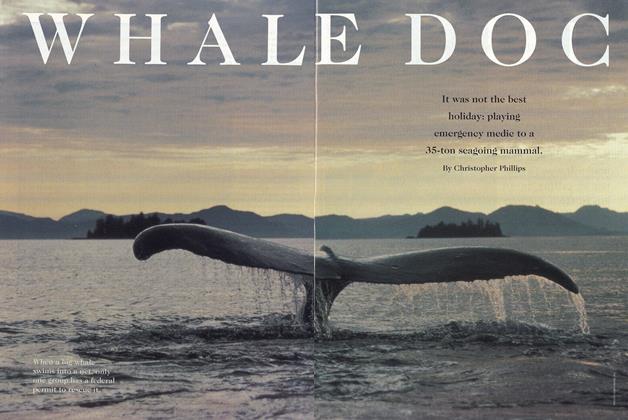

FeatureWHALE DOG

February 1994 By Christopher Phillips -

Article

ArticleDr. WHEELOCK'S JOURNAL

February 1994 By "E. Wheelock" -

Article

ArticleA Year and a Tree, Both Rededicated

February 1994

Features

-

Feature

FeatureAffirmative Action

April 1975 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryJames M. Phillips '80

March 1993 -

Feature

FeatureADRIAN W.B. RANDOLPH

Sept/Oct 2010 -

Feature

FeatureThayer School Report

April 1939 By John S. Macdonald '13 -

Feature

FeatureThe Ultimate Guide

Jan/Feb 2013 By MARGARET WHEELER AS TOLD TO JIM COLLINS '84 -

Feature

FeatureTHE CLASSICS

March 1962 By NORMAN A. DOENGES