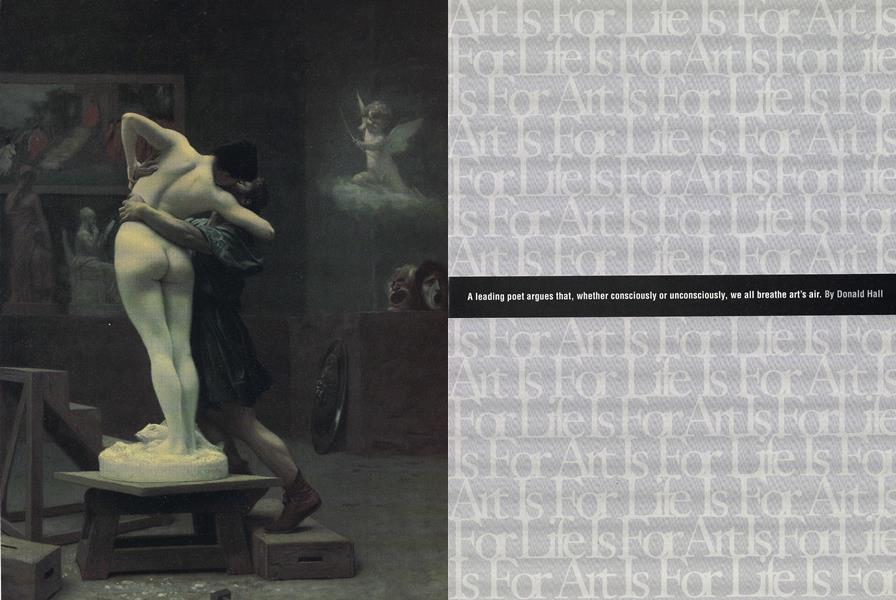

A leading poet argues that, whether consciously or unconsciously, we all breathe art's air.

FEBRUARY 1994 Donald HallA leading poet argues that, whether consciously or unconsciously, we all breathe art's air. Donald Hall FEBRUARY 1994

When the election results looked certain, November of 1992, my friend Bailey, who works in finance but withholds himself from the Republican Party, telephoned for an orgy of mutual congratulations. With excitement, I mentioned that President Clinton would make good appointments in the arts—to run the National Endowment, for instance. Bailey laughed at my provincialism; his major worries are deficits and entitlements. "Art's not exactly my top priority," he said.

Yet when Bailey went home, he returned to a vast CD collection, a houseful of objects of art, and a thousand books. He went home to read good prose in a well-designed chair under a handsome print while he listened to music. Or maybe Bailey and his wife went out that night, to catch Eric Bogosian in performance, or to hear a jazz quintet. He lives breathing art's air, and does not acknowledge the priority art occupies in his life.

For me, it's obvious enough: As a poet, I try to produce art; the rest of my day, I intend to consume it. I take art in like many people—in order to keep myself sane and whole and reasonably happy. Art is a pleasure, but unlike simpler pleasures say, an ice-cream cone art enhances human consciousness; it organizes the sensibility, discovering order and shape in the multiplicity of experience; without good art and design around us, our minds fray among a welter of unrelated particulars. I claim for art in general what William Carlos Williams claimed for poems: that "men die miserably every day/ for lack/ of what is found there." Art is for life is for art is for life.

It helps to start early. If we go to college, college is a time to fill our carts with supplies for the long and sometimes tedious journey. Later when we practice law in Boston, or advise people on their estates in Ohio, or manage a refinery in Oklahoma, we will seldom visit the Hood Museum. Better visit it when you're a student, to hang its great paintings in the mind's gallery alongside theater and music. The more art we gather into ourselves when we are young, the more we equip ourselves to enjoy it later. The more we live with art day by day, breathing its air, the more we organize and sweeten the texture of our lives.

It's common to condescend to art—not possessing the highest priority even among the people whose daily lives are most lightened and lit by it. Doubtless as Eratosthenes in fifth-century Athens walked home with Laodice from a government-sponsored Sophoclean performance, past sculpture and architecture commissioned from Pheidias and Ictinus by Periclean gold, he deplored spending the treasury's wealth on painting while some citizens in this great democracy were so poor that they could hardly keep a slave.

Doubtless, Laodice agreed that we should not fund a dance company because of the homeless; that we should withhold money for orchestras because crack cocaine rules city streets; that we should starve art museums in order to nurture medical research. In the perennial song of the urgencies, art is always expendable. There's never a moment when we cannot name something more essential to support than a song or a picture or a story; yet we live and die, we understand ourselves

and others, we cherish and extend our humanity by stories, pictures, and songs. Art is a source of the compassion by which we prefer funding misery over funding the arts.

We take art for granted, as if it were there like a hill or a wildflower, as if it flourished naturally and without human care. We retreat when art is attacked; when bigots trash the NEA, even political liberals suggest that the government retreat from supporting art: The art-kitchen gets hot, so we suggest burning down the kitchen. If Pericles had listened to David Brinkley, or Eratosthenes, there would be no Parthenon and without a Parthenon, without a Delphic charioteer, without an Oedipus Rex, we would be worse off than we are. Because of occasional victories by know-nothings and iconoclasts, we are worse off than we might have been: Barbarians (Senators, columnists) melt the statues down; continually, we model the statues again to magnify human consciousness.

Art needs support. Renaissance painting and sculpture rose from the treasuries of princes both secular and sacred; opera, symphony, and dance came from the fortunes of the dukes and squires of Europe. Art has never supported itself; art is no virtuous puritan merchant, surviving in the marketplace by selling tickets or by charging admission. (When art-bashers ask the arts to support themselves, they call upon art to vanish.) In Europe, ticket sales account for 20 percent of the costs

of music, dance, and the performing arts. In America, these sales account for as much as 40 percent: no more than that, and the rest comes from patronage.

Without democracy, rich rulers hold power by wealth and wealth by power; with democracy, taxation supports popular institutions only in cities where rich patrons are concentrated. In the last 25 years, through government seed money administered by the National Endowment, opera companies (and small publishers and art museums and regional theaters) have flourished in smaller cities from coast to coast. These institutions in their turn serve rural places: I have watched dancers from the Boston Ballet perform in the old opera house of Newport, New Hampshire. There it was the beauty of the body in motion, available to anyone—at Newport's Opera House. So it is in the open places of Oklahoma and Idaho; so it is in industrial Ohio and Michigan. We need the arts everywhere among soybeans and highrises, among inner cities and rollingmills to enhance our lives, even to reconcile us to our human condition. Be it jazz or tragedy, art expands human consciousness, and this enlargement is a worthy goal. Art makes apprehensible shapes out of random natural sources. Take all the sounds possible to the world, from birdsong to foghorn, organize the sound by scale and tempo, and sound turns into music. Replying, music organizes our ears to hear birdsong and foghorn. Literature derives from a haphazard of smells, visions, motives, and emotion—ordered by imagination and skilled language into purpose and resolution. Design, as well as great painting, informs the vision, making shapes by arranging the always-available manyness of color and form. Art extends human consciousness by capturing and making comprehensible the welter of sensations, sounds, and stories.

In the millennia since civilization divided labor, our jobs have specialized and isolated us from a view of the whole world. If we are lucky, our work can provide deep satisfaction it is glorious to teach kindergarten; socially necessary to provide life insurance; useful to build bowling alleys and pickup trucks—but no job reaches into all crannies of die soul; at least there remains room or necessity for other matter to enlarge and extend us a necessity that art fills. What do we do, after we come home from office, school, factory, or bowling alley: we eat, we drink, we play with our children. Better we eat good food from plates that are shapely and designed for beauty better for the quality of consciousness: Design is nutrition for consciousness as food is for body. Children's toys are beautiful or they are ugly; choosing the toys our children live with, we choose the mental ambiance they grow up in. Apprehension of beauty in ordinary things—teacups, teddy bears, and pillowcases—shapes the sensibility.

Art affects us when we don't notice it and when we do. In my own art of language, poetry is the extreme of arrangement: But the mathematics of poetry's formal resolution does not preclude m oral thought, or satisfaction in honest naming, or the consolation of shared feeling. When someone dear to me dies, I go back to certain poems from the seventeenth century for consolation. Poetry is an extreme of beauty and control, but language thrives elsewhere as well: We may discover a prose arithmetic of satisfaction in great novels or in the daily press, Sometimes, I read reviews of rock music in the Globe or Greil Marcus in the Voice despite my musical ignorance, in order to take pleasure in the justice of syntax or epithet.

We consume art when we go to hear the opera or the folk guitar; we consume it in the afternoon we spend at the art museum. Most of us also produce: learning to throw a pot; or working with a committee on the design of the library addition; or in the office attending to the language'of a brochure. We produce arts or crafts when we sew or build, with or without a modicum of talent, and we learn better to read (or hear or see) a medium in which we participate; the best cook is the best eater. But no one can produce all the time, and Picasso sat still to hear the guitar. We consume art to strengthen the mind's precincts and the soul's avenues, making a city for living in—for the whole of our lives and for our lives' wholeness. No one is born sensitive to all art; we may improve and enlarge our pleasures by extending the borders of appreciation. If we appreciate jazz but feel deaf to symphonic music, an exercise of attention will accrue greater accessibility to joy. Dutch painting, contemporary poetry, African woodcarving the eras and genres of the whole world open themselves to pleasure through understanding. Life is for art is for life.

But if art be not continuous into the present day, our dilettantish appreciation of the past may separate us from our own day's air and policy. To the practiced sensibility, past art remains present while present art makes the past accessible. Privately, we owe it to ourselves to be open to a continuum of the arts; publicly, it is our responsibility to enable the arts of our own day. It is only self-serving to support the arts, to support political candidates who disdain underwriting of music, painting, theater, literature, dance, sculpture, and design. Is this elitist? Only in the service of dragging everybody, kicking and screaming, into an elite of pleasure and understanding.

WITHOUT GOOD ART AND DESIGN AROUND US, OUR MINDS FRAY AMONG A WELTER OF UNRELATED PARTICULARS.

COLLEGE IS A TIME TO FILL OUR CARTS WITH SUPPLIES FOR THE LONG AND SOMETIMES TEDIOUS JOURNEY.

AS A POET, I TRY TO PRODUCE ART; THE REST OF MY DAY, I INTENDTO CONSUME IT.

TAKE ALL THE SOUNDS POSSIBLE TO THE WORLD, FROM BIRDSONG TO FOGHORN, ORGANIZE THE SOUND BY SCALE AND TEMPO, AND SOUND TURNS INTO MUSIC. REPLYING, MUSIC ORGANIZES OUR EARS TO HEAR BIRDSONG AND FOGHORN.

IN THE PERENNIAL SONG OF THE URGENCIES, ART IS ALWAYS EXPENDABLE.

ART IS A SOURCE OF THE COMPASSION BY WHICH WE PREFER FUNDING MISERY OVER FUNDING THE ARTS.

The Poet Laureate of New Hampshire, Donald Hall won the NationalBook Critics Circle Award in 1988.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

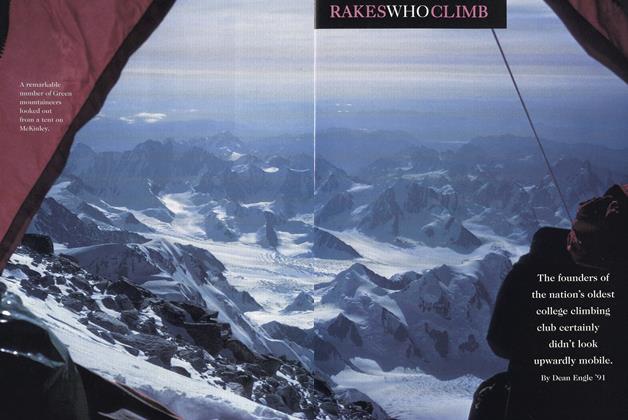

FeatureRAKES WHO CLIMB

February 1994 By Deab Engle '91 -

Feature

FeatureTau Iota Tau and Other Brassy Memories

February 1994 By Regina Barreca '79 -

Feature

FeatureONCE UPON A CRIME

February 1994 By Lawrence Treat '24 -

Feature

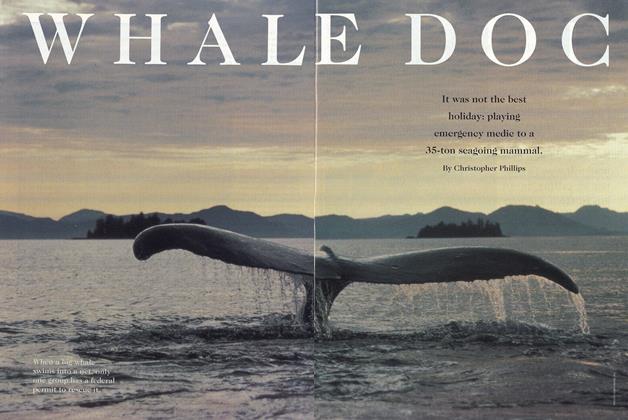

FeatureWHALE DOG

February 1994 By Christopher Phillips -

Article

ArticleDr. WHEELOCK'S JOURNAL

February 1994 By "E. Wheelock" -

Article

ArticleA Year and a Tree, Both Rededicated

February 1994

Features

-

Feature

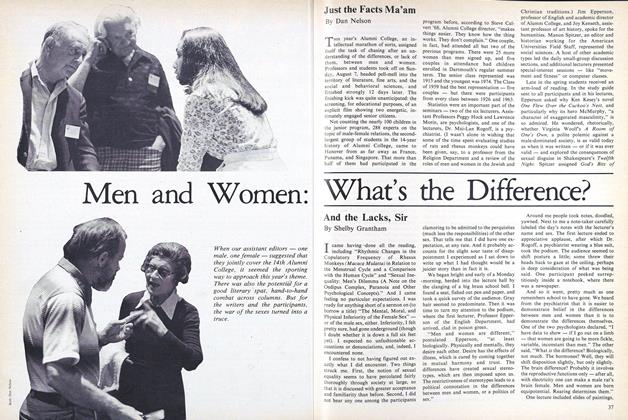

FeatureMen and Women: What's the Difference?

OCT. 1977 By Dan Nelson, Shelby Grantham -

Feature

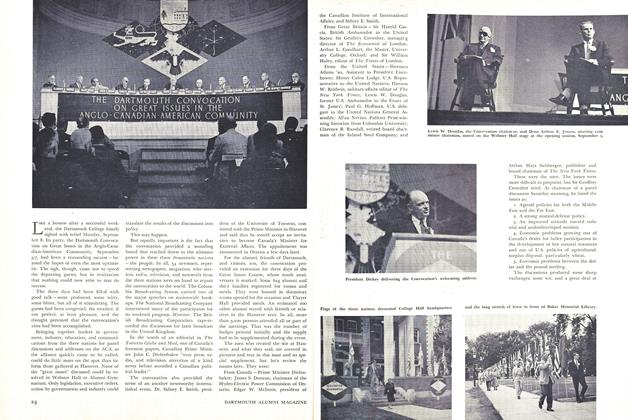

FeatureTHE DARTMOUTH CONVOCATION ON GREAT ISSUES IN THE . ANGLO – CANADIAN – AMERICAN COMMUNITY

October 1951 By GEORGE O'CONNELL -

Feature

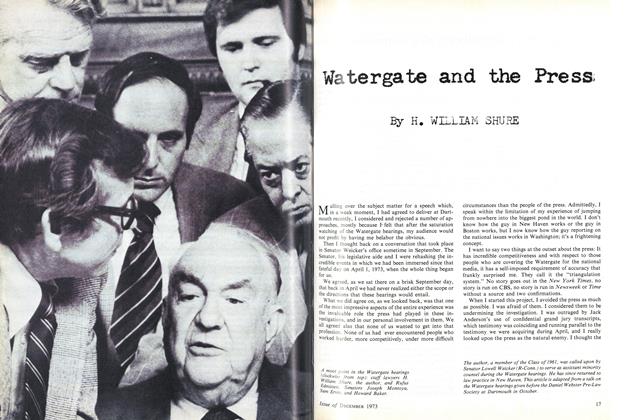

FeatureWatergate and the Press

December 1973 By H. WILLIAM SHURE -

Feature

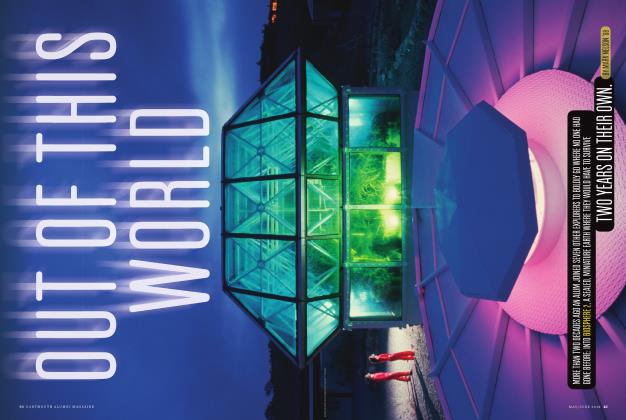

FeatureOut of This World

MAY | JUNE 2018 By MARK NELSON '68 -

Feature

FeatureOur Place in the Sky

November 1959 By PROF. MILLETT G. MORGAN