ON A BRIGHT, CLEAR Afternoon in February, Dartmouth held a memorial service for one of her finest sons, Marshall T. Meyer '52. The occasion in Rollins Chapel gave me an opportunity to reflect upon Rabbi Meyer's signal contributions to his fellow human beings.

Marshall Meyer will be remembered for the power of his faith, for the force of his commitment to social justice, for his passion and eloquence, and for the heroic contribution he made to bettering the lot of humankind—in this country and in Latin America.

Marshall often said that his four years at Dartmouth—and especially a senior fellowship undertaken, he said, "to investigate my Judaism"—were instrumental in shaping his values and forming the convictions that led to his decision to become a rabbi.

Rabbi Meyer wrote about the impact that one Dartmouth professor, T.S.K. Scott-Craig, had on his life: "I can still hear his voice saying, 'Gentlemen, it's more important to find what the real question is. The answers change, but the questions change as well, and you must be aware of what question your soul is asking at different moments of your life.' That's one of the great statements I've always held with me," he said.

In looking back upon Marshall Meyer's life and the remarkable work that he leaves as part of his legacy, I could not help but notice how much of what we admire in him stemmed from his ability to listen carefully to the questions his soul put to him, and from his unfailing courage and strength in living out his answers to those questions.

Marshall Meyer was graduated from Dartmouth in 1952 and ordained at New York's Jewish Theological Seminary in 1958. The next year his parents died, and again, Meyer listened to the question as well as to the answer. He asked the World Council of Synagogues to send him temporarily to a post overseas. He was sent to Buenos Aires for what he thought would be a year or two. He stayed for 25 years.

He saw the poverty and suffering around him and recognized it for the injustice it was. He also saw what wasn't there: a sufficient supply of rabbis. There were only 20 rabbis to serve 850,000 Jews in all of Latin America, including Mexico. And so he founded Latin America's first rabbinical seminary, in order that Judaism and the life of the spirit for those 850,000 Jews might not die with those few rabbis.

In due course, he embarked upon an editorial program, publishing a bilingual edition of the entire Jewish liturgy—the first since the Jews were expelled from Spain in 1492. He founded what is now the largest synagogue in Buenos Aires, incorporating the Spanish language and young men and women into the services. He

1 said he "wanted a synagogue where young people would bring their parents, not where adults would drag their children." And he confronted the political and social injustices around him.

From the very beginning of his work as a rabbi, Marshall was committed to social action. "Judaism that is not involved in social action is a contradiction in terms," he said. As the New York Times reported, he "became a thorn in the side of the military dictatorship that seized power [in Argentina] in 1976."

At great risk to himself and his family, he spoke up early and loudly on behalf of "los desaparecidos," the disappeared." Again, he heard the questions from within: "In the face of all this misery, how can I, as a Jew, keep quiet? How can I, as a human being, keep quiet?" And he acted out the answer with the force of his entire life.

He counseled the families of the disappeared, ministered to prisoners, and exerted pressure on the government to release those who were being held in prison for years without being charged. One former prisoner, Jacobo Timerman, dedicated his book, Prisoner Without a Name, Cell without aNumber, to "Marshall Meyer, a rabbi who brought comfort to Jewish, Christian and atheist prisoners in Argentine jails."

Dartmouth paid homage to Rabbi Meyer's commitment to human rights by conferring upon him, in 1982, the honorary degree of Doctor of Humane Letters. And, after the election of Raul Alfonsin as President of Argentina in 1983, Meyer was awarded the Order of the Liberator San Martin, Argentina's highest tribute for a non-citizen.

In 1985 came the call for him to become the rabbi of Congregation B'nai Jeshurun on the Upper West Side of Manhattan. The oldest Ashkenazic Conservative congregation in New York City, it had dwindled to 80 families. With characteristic energy and passion, Marshall Meyer led a spiritual and physical revival of the synagogue, which now serves a thousand families from around the metropolitan area. He was deeply involved in a myriad of social outreach programs—interfaith initiatives, shelters for the homeless, solace and care for those with AIDS.

The final question that Marshall's soul asked him came last December, when doctors informed him that he had cancer. As he told his wife, Naomi, "If I can't show my family and my congregation how to face death, what kind of rabbi am I?" The answer is that he was a rabbi who lived out his last weeks as he had lived his entire life: by going about his life's work as best he could—ministering to his congregation and serving his brothers and sisters of every creed and every race.

We honor Marshall Meyer because he listened to the questions of his soul and summoned the moral strength to live out his answers. By the exemplary way in which he led his life, Marshall Meyer reminds us, as Albert Camus once wrote, that we must not "wait for the Last Judgment. It takes place every day."

"Rabbi MarshallMeyer acted out theanswers with the forceof his entire life."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

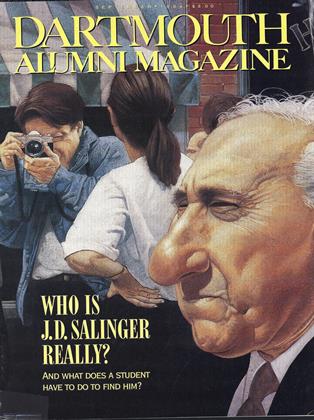

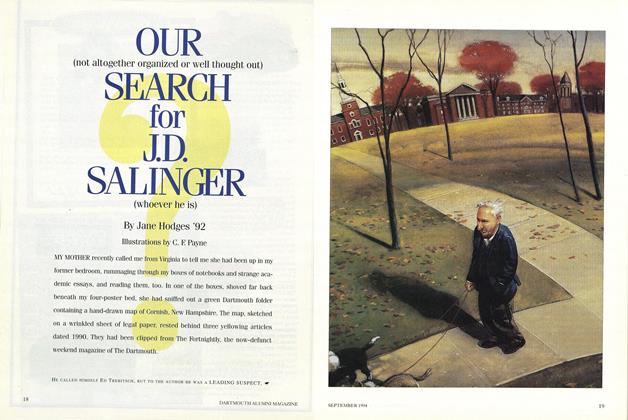

Cover StoryOUR SEARCH FOR J.D. SALINGER

September 1994 By Jane Hodges '92 -

Feature

FeatureTales from the Info Booth

September 1994 -

Feature

FeatureThe Run

September 1994 By Stephen Madden -

Article

ArticleSEX AND THE DEVIL

September 1994 By Karen Endicott -

Class Notes

Class Notes1994

September 1994 By Nihad Farooq -

Class Notes

Class Notes1947

September 1994 By Ham Chase

James O. Freedman

-

Feature

FeatureThe President's In-box

June 1987 By JAMES O. FREEDMAN -

Article

ArticleTHE PROFESSOR'S LIFE

FEBRUARY 1991 By James O. Freedman -

Article

ArticleLessons of the Law

NOVEMBER 1992 By James O. Freedman -

Article

ArticleSkepticism and the Refined Mind

SEPTEMBER 1996 By James O. Freedman -

Article

ArticleStaying Out of the Groove

SEPTEMBER 1997 By James O. Freedman -

Article

ArticleWomen and Men of Dartmouth

OCTOBER 1997 By James O. Freedman