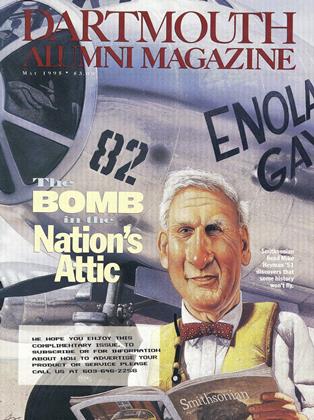

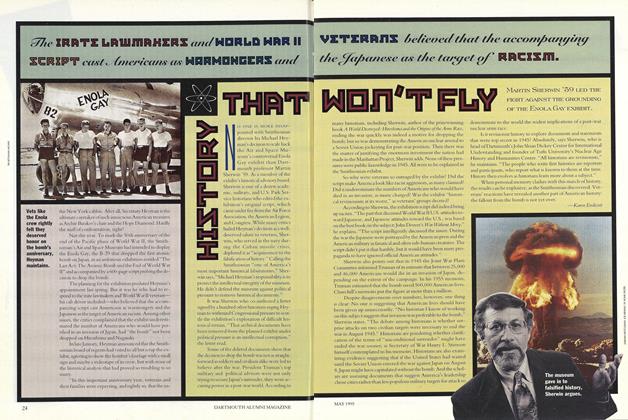

THE NEW HEAD OF THE SMITHSONIAN, IRA MICHAEL HEYMAN '51, FINDS HIMSELF IN A POLITICAL FIRESTORM OVER THE ENOLA GAY. WHIGH RAISES THE QUESTION: SHOULD OUR FEDERAL MUSEUM CONTAIN HISTORY OR ICONOGRAPHY?

AT SIX-FEET FIVE, IRA MICHAEL HEYMAN '51 IS A BIG BEAR OF A MAN WHO DOES NOT RATTLE EASILY.

But there he was in a taxi rumbling tlarougli Manhattan one day this winter, his trademark bow ttie firmly in place, when the driver realized his passenger was associated with the Smithsonian Institution.

"Sons of bitches!" the driver suddenly cried out.

Until recently, it would have Been hard to imagine the Secretary of the Smithsonian a most dignified official who oversees the" 16 museums affectionately known as the nation's attic getting a tongue-lashing from that quintessential American pundit, the New York cabbie . After all, Secretary is the ultimate caretaker of such innocuous American treasures as Archie Bunker's chair and the Hope Diamond. Hardly the stuff of confrontation, right?

Not this year. To mark the 50th anniversary of the end of the Pacific phase of World War II, the Smithsonian's Air and Space Museum had intended to display the Enola Gay, the B-29 that: dropped the first atomic bomb on Japan, in an ambitious exhibition entitled "The Last Act: The Atomic Bomb and the End of World War II" and accompanied by a 600-page script probing the decision to drop the bomb.

The planning for the exhibition predated Heyman's appointment last spring. But it was'he who had to respond to the lawmakers and World War II veterans his cab driver included who believed that the accompanying script cast Americans as warmongers and the Japanese as the target of American racism. Among other issues, the critics complained that the exhibit underestimated the number of Americans who would have perished in an invasion of Japan, had "the bomb" not been dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

In late January, Heyman announced that the Smithsonian board of regents had voted to all but scrap the exhibit, agreeing to show the bomber's fuselage with a small sign and maybe a videotape of its crew, but with none of the historical analysis that had proved so troubling to so many.

"In this important anniversary year, veterans and their families were expecting, and rightly so, that the nanation would honor and commemorate their valor and sacrifice," Heyman said, in remarks reported on the front page of The New York Times. "They were not looking for analysis and, frankly, we did not give enough thought to the intense feelings such analysis would evoke."

For Mike Heyman, it was yet another brush with controversy in a career that has had more than its share. As chancellor of the University of California at Berkeley from 1980 to 1990, he Oversaw the wholesale overhaul of his student body's ethnic and racial composition, making it the first major research university in the nation at which no group constituted a majority. And as a Dartmouth trustee from 1982 to 1993, the last two years as chairman of the board, he wrestled with a host of hot-button issues, from the College's investment policy toward companies doing business in South Africa to its participation in ROTC despite the military's continuing intolerance toward gays in uniform.

Still, the 64-year-old New York City native says none of his previous experiences compared to being caught in the buzz saw of a full-blown national debate that dredged up sharp emotions toward a war fought half a century ago.

"I'vebeen through an awful lot of these things," he said during a Sunday morning interview With this magazine at his Washington home, less than a week after the regents' decision. "But I just find this very different,"

IT WASN'T SUPPOSED TO BE LIKE THIS. When he was tapped by the regents last year to lead the Smithsoman into the twenty-first century, Heyman imagined a job that "would be considerably more sedate than it has proved to be," he recalled with a laugh.

Instead, he would draw headlines again, a month after resolving the Enola Gay dispute, for suggesting that the Smithsonian might soon be forced to charge admission a prospect that would hardly thrill taxpayers if Congress made good on threats to slash its budget. (The $371.1 million that the Smithsonian received in federal tax dollars last year represents about 77 percent of its total funding, which is supplemented by grants and corporate donations.)

He has also said that, after decades of steady expansion, the Smithsonian might have to consider "going out of business" in some of its museums, most of which are located on the National Mall in Washington. He is far too politically savvy, of course, to disclose which ones are under consideration.

"I would rather not," he said. "But mayhe that is going to be required."

And then there are the more philosophical questions as to the evolving role of the Smithsonian, which was bequeathed to the nation more than 150 years ago by a British scientist, James Smithson with a broad mandate to further the "diffusion of knowledge."

Should the Smithsonian which devotes half its resources to research at 11 less-publicized facilities provide provocative interpretations alongside the items it displays from its huge collections? Or should it merely post small, identifying signs inside its galleries and leave the rest to the viewer's initiative:?

"I think there is a real place for interpretation," Heyman says emphatically. "Not everything is just looking at icons like the Spirit of St. Louis or the red slippers from The of OZ"

But there is, he quickly adds, a time and place for analysis. And as a former marine who served stateside during the Korean Conflict, he agrees with those veterans who implored the Smithsonian to do nothing more than commemorate the Second World War this year.

"You've got over a million people who fought in that war, all of whom thought that they were going to invade Japan and believed that their lives were saved by the dropping of the bomb," he said. "They don't want to hear, at this moment, some big analysis of 'Hey, maybe there were other reasons for dropping the bomb' or Maybe you didn't have to drop the bomb.'"

In 1945, the' year the bomb was dropped, Mike Heyman was a 15-year-old high school student at the Horace Mann School for Boys in the Bronx, where he played football and got solid grades. Two years later he applied to Dartmouth. Retired radio talk show host John A. Gambling '51, who lived with Heyman on the top floor of Lord Hall, remembers him as "a great roommate" and "a serious government major with, from as long as I could remember, his eyes set on a law degree." When not at Theta Chi or the radio station, Heyman spent many of his weekends at Smith College visiting his girlfriend, Therese Thau, whom he had known since he was 13. The couple, who married senior year, celebrated their 44th wedding anniversary this past December.

After Dartmouth Heyman spent two years in the marines at Camp Pendleton in California before entering Yale taw School, where he made law review. He worked for a year at a Wall Street firm, clerked for a federal judge in New Haven, and then reeled in a dream job senior clerk to U.S. Supreme Court Chief Justice Earl Warren. He landed at Berkeley as a law professor in 1959, building a specialty in property and zoning law. It was during that time that this liberal New York Republican became a liberal California Democrat. " California really had gone very right," he recalled, "and I was just very uncomfortable."

Before long he was Rising the ranks of the Berkeley administration, first as vice-chancellor and then as chancellor. One of the first issues he tackled as chancellor was developing a systematic way for the university to raise money, something it had never done particularly effectively. The results were impressive: over the course of his tenure donations more than tripled, rising from $31 million in 1980 to $100 million in 1988.

It is all the more impressive that Hey man managed to raise so much money at a time when he was radically remaking Berkeley's racial and ethnic complexion helping boost the percentage of nonwhite undergraduate students at the university from 27 percent in 1980 to 51 percent in 1988. It was a process that was not without pain: Some professors lamented that Heyman had brought on too'much change too fast, and some Asian-American groups, whose numbers dropped under the new admissions policies, complained that they were being left out. In March of 1989, Heyman conceded that the policies were a "product of insensitivity" and had had a negative effect on Asian-Americans.

Today he has no regrets. Indeed, he says, he is proud that the next generation of California's leaders will be some of those students who might not have gotten into Berkeley previously. Of the Asian- Americans who took issue with his policies, he now says: "The insensitivity was that we didn't talk to them and tell them what was going on."

"On the other hand," he adds a moment later, "there are so many things, I have learned now in life, that just had to happen."

In 1987, five years after he had been nominated by the Dartmouth Alumni Council to the Board of Trustees, Heyman served on the presidential search committee seeking a successor to David T. McLaughlin '54. At a meeting of university administrators in Washington that spring, not long after James O. Freedman had been offered the job, Heyman pulled his old friend into the corner of a hotel lobby to persuade him that he should leave the University of lowa and accept the offer.

It is a conversation that President Freedman remembers as "pivotal" in his decision to came to Hanover, with Heyman selling him on the idea of Dartmouth as "a jewel of a college" that would give Freedman "the opportunity to do those things he thought I did best, to speak to intellectual quality." Since then, Freedman said he has repeatedly turned to Heyman for advice. "When he puts that big arm around your shoulder," the president said, "you teel reassured."

After ten years as Berkeley chancellor, having served longer than any of his predecessors, Heyman stepped down in 1990 to return to teaching law. He did not last long. Realizing he had missed out on an enormous amount of scholarship in his field, he wrote a letter to Interior Secretary Bruce Babbitt in 1993 asking if he had room for a legal advisor who could add experience to a young department. Babbitt took the bait. So Mike and Therese, a curator at the Oakland Museum, temporarily shuttered their home in Berkeley to move back East.

A regent of the Smithsonian since 1990, Heyman chaired the committee to find a replacement for retiring Secretary Robert McC. Adams. Before long, the regents asked Heyman to put his own hat in the ring, something he said he did with great reluctance. Within months he was the first non-scientist ever to head the Smithsonian.

Heyman's dreams for the institution, which he says he will not run past his 70th birthday, are similar to his initial goals at Berkeley: to make it accessible to more people and to fundraising base in the private sector. Heyman hopes to introduce a new Crop of electronic visitors to the Smithsonian through future exhibitions on the Internet, CD-ROM, and perhaps a new museum cable channel. Most of the programs, He says, will be aimed at "people who can't come to Washington but want to share in the things we do."

Heyman will also be keeping an eye on the construction of the American Indian Museum, a much-anticipated gallery scheduled to open in the last vacant spot on the Mall next to Air and Space and across from the National Gallery of Art in 2001.

Less than a year into his tenure at the Smithsonian, Heyman's reviews have been generally favorable, although though not without their knocks. Among those marking his report card is Maxine Singer, the chairman of the Commission on the Future of the Smithsonian, a citizens group that reports directly to the regents. Echoing the sentiments of others, Singer says she wishes Heyman had made the Enola Gay decision less of a political one, deferring to the curator of the Air and Space Museum rather than cowing to pressure that he intervene.

Nevertheless, she says she gives him high marks overall for always staying in "good spirits," particularly while weathering "the kind of nightmare that Washington hands out to people who come here to do important jobs."

As a former Dartmouth trustee and Berkeley knows controversy.

Vets likethe Enolacrew rightlyfelt theydeservedhonor onthe bomb'sanniversary,Heymanmaintains.

Heymansays thereis a timeand placefor analysis,but theEnola Gayexhibitwasn't it.

The Irate Lawmakers and World War II Veterans Believed that accompanying Script cast Americans as Warmongers and the Japanese as the target of Racism.

“There is a Real Place for Interpretation. Not everything is just Looking at Icons like The Spirit of St. Louis or the Red Slippers from the Wizard of Oz.”

JACQUES STEINBERG is a reporter for The New York Timesand a former editor-in-chief of The Dartmouth.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

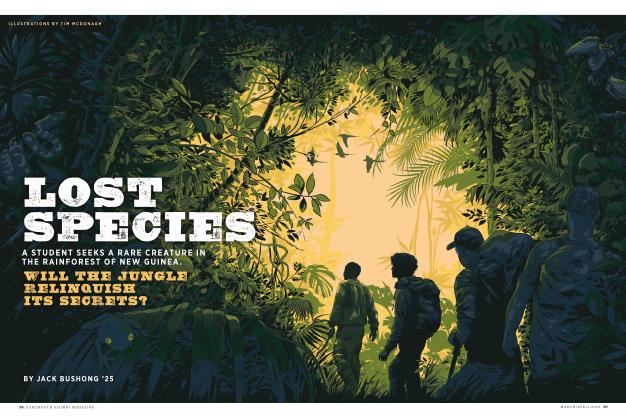

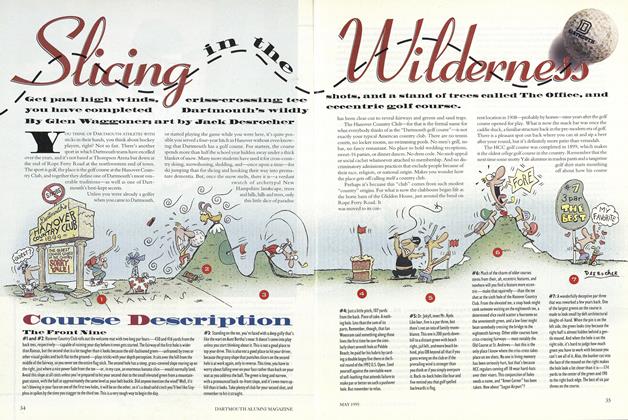

FeatureSlicing in the Wilderness

May 1995 By Glen Waggoner -

Feature

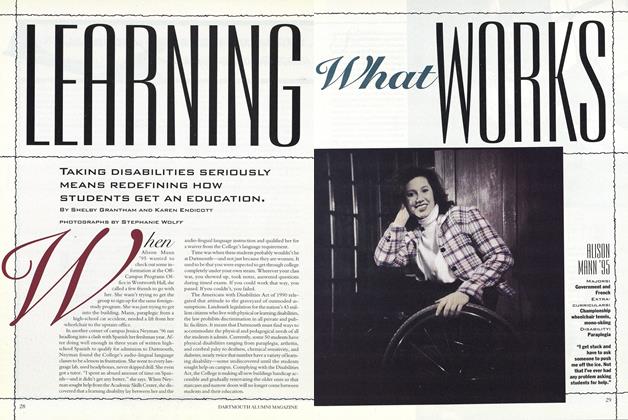

FeatureLEARNING WHAT WORKS

May 1995 By Shelby Grantham and Karen Endicott -

Article

ArticleCosmic Bubble Bath

May 1995 By Karen Endicott -

Article

ArticleDivers Notes & Observations

May 1995 By "E. Wheelock" -

Article

ArticleHISTORY THAT WON'T FLY

May 1995 By Karen Endicott -

Class Notes

Class Notes1980

May 1995 By Daniel Zenkel

Jacques Steinberg '88

-

Continuing Education

Continuing EducationPaul Binder '63

Nov/Dec 2000 By Jacques Steinberg '88 -

Continuing Education

Continuing EducationAnita Hamilton '89

Jan/Feb 2001 By Jacques Steinberg '88 -

Continuing Education

Continuing EducationJeffrey Immelt '78

May/June 2001 By Jacques Steinberg '88 -

Interview

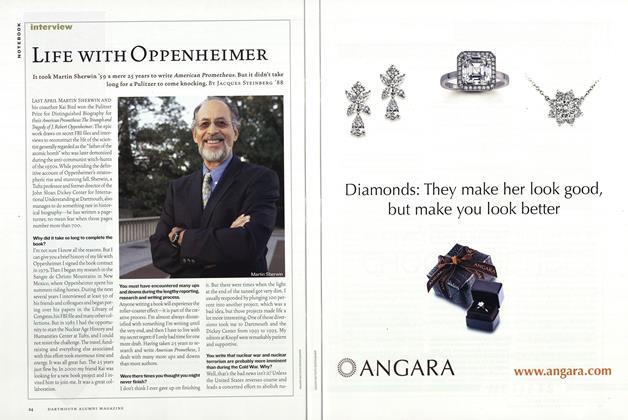

InterviewLife with Oppenheimer

Jan/Feb 2007 By Jacques Steinberg '88 -

Interview

Interview"There's a Convergence"

Sept/Oct 2007 By Jacques Steinberg '88