The College President returned to the classroom as political history was being made.

ON JANUARY 41 walked into a classroom as a teacher for the first time since I became dean of the faculty in 1989. After the Board of Trustees invited me to be the sixteenth president of Dartmouth, I decided to resume teaching. Doing so would, I knew, carry symbolic value. Dartmouth's research faculty takes undergraduate teaching very seriously; my teaching would emphasize this commitment. There was also a personal motivation: I truly missed teaching.

I arranged to coteach my old "Twentieth-Century American Political History" course with Professor Ron Edsforth. Happily, the course coincided with a longs-cheduled winter-term program that the Ken and Harle

Montgomery Endowment at Dartmouth sponsored assessing "Power and the Presidency" in this century. The series brought Presidential biographers David McCullough, Robert Caro, Doris Kearns Goodwin, Michael Beschloss, Edmond Morris, and David Maraniss some of the best biographers of our age to campus to meet with students and present public lectures.

I first taught about the American Presidency in January of 1970. Richard Nixon was just completing his first year in the White House, and we concluded the term with a discussion of the 1968 election. Students affected a jaded view of the world, yet shared a sense of idealism and the efficacy of politics.

Over the next 20 years the subject matter enlarged: Watergate and Nixon's resignation, the Ford and Carter years, the rise of conservatism and the Republican Party, the decline of the old Democratic Party alignments, the shifting politics of the South, the Reagan years. Students continued to be interested in political history, but they became more detached, less personally involved in politics.

My last lecture this term was on "The Clinton Years." As I was planning the lecture, the impeachment proceedings were still underway. But writing under those circumstances was a good exercise, a reminder that historians are not pundits on current events but can provide a context for understanding them. These insights should have a value independent of the way the immediate matter was resolved.

As people on all sides of the Clinton imbroglio invoked "history" to support their views, I hoped my students would recognize that history seldom shouts its lessons. Cause and consequence are not always neatly related. In truth, most of us who choose to become professional historians thrive on ambiguity even as we insistently attempt to reduce it.

Of course there are powerful moral lessons at play here. And, equally obviously, historians can point out that partisanship, hubris, self-righteousness, self-indulgence, hypocrisy, and lying are not new things. American political history has always had its full share of characters and clowns, of meanspirited demagogues, of powerful ambitions, and of paranoia.

But there are some powerful history lessons here as well that derive from themes that have increasingly shaped American politics for the past few generations. Partisanship in the Congress has increased while partisanship and voting among the public has declined. Executive and Congressional collaboration on policy formulation—and on most things has declined. Issues that do not lend themselves to compromise have been politicized and we are increasingly relying upon our judicial system to resolve these troubling differences. Political media (such as cable channels, talk-radio, the Internet) are often guided by passion rather than facts or logic. Traditional electoral coalitions have splintered while focused electoral groups have strengthened with great consequence for elections and for the ways members.of Congress and the President define "their" constituencies.

Popularity and electability now seem more related to public posture than public accomplishments. The ability to broker partisan consensus and bipartisan compromise used to characterize the true political leaders. Today, for many, standing for the "right things" counts for more than progress with the pressing and complicated agenda of the Republic. Now we have come to this: a President who conducts himself in a way which a majority of citizens disapprove and a Congress that proceeded with action which a majority of citizens disapproved. And the President and his major antagonists in the House all are apparently secure in the approval of "their" supporters.

I hope my students come to recognize that history is not a discipline, like the law, which seeks precedents that can prescribe and encumber. The themes of history are neither inevitable nor inescapable. A study of history affirms that humans are free agents who can make free choices, and often the most dangerous of these free agents are those who insist that they are compelled by history, that they have history on their side, or that they can be confident how historians will judge them.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

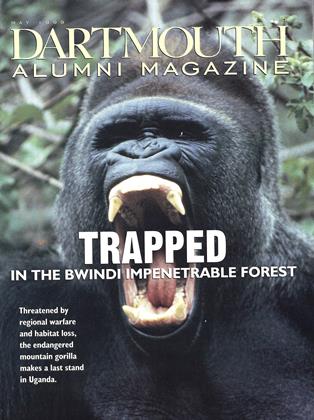

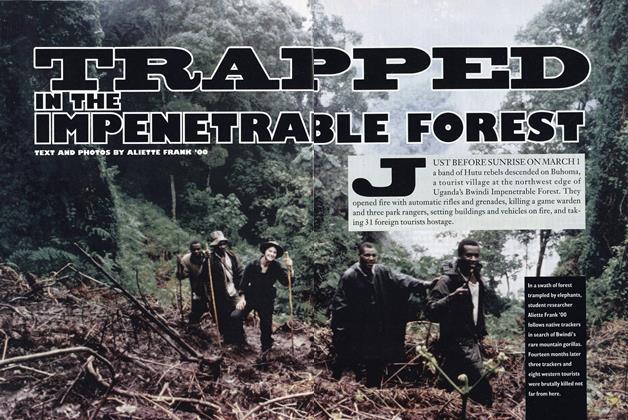

Cover StoryTrapped in the Bwindi Impenetrable Forest

May 1999 By ALIETTE FRANK '00 -

Feature

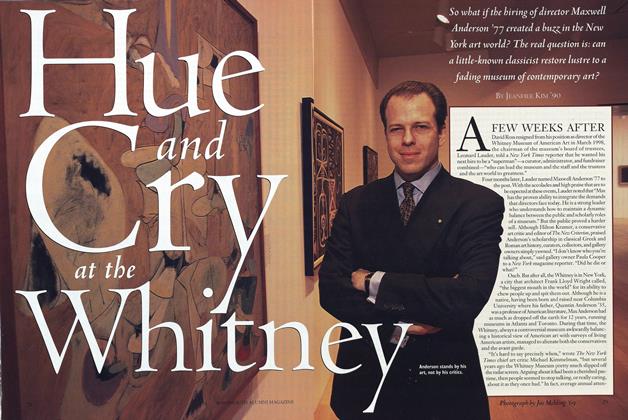

FeatureHue and Cry at the Whitney

May 1999 By Jeanhee Kim '90 -

Feature

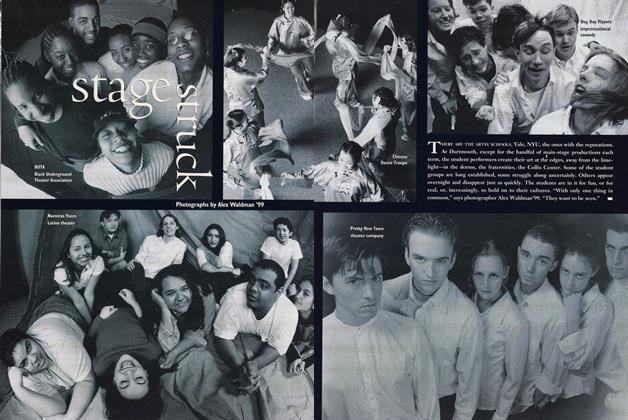

FeatureStage Struck

May 1999 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1971

May 1999 By Don O'Neill -

Article

ArticleThe Financing Game

May 1999 By Noel Perrin -

Article

ArticleThe Masculine Mystique

May 1999 By Suzanne Leonard '96

James Wright

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryDartmouth's Steady Course

MARCH 1990 By James Wright -

Feature

FeatureWAR AND REMEMBRANCE

December 1995 By James Wright -

Feature

FeatureDartmouth's Balance

MAY 1997 By James Wright -

Interview

Interview"We Expect Excellence"

May/June 2005 By James Wright -

Feature

FeatureBattle Scarred

Sep - Oct By JAMES WRIGHT -

notebook

notebookGood Neighbor

NOVEMBER | DECEMBER 2020 By JAMES WRIGHT