IN THE PALL. of 1949 I took Professor John Wolfenden's basic chemistry course. Wolfenden had a soft British accent and gentle manner that made me think I was going to like the professor but not the subject. And that was right. It was only a few weeks until Wolfenden knew he had a problem, a chemistry misfit on his hands. I would flunk a quiz, and he would meet with me with patience and encouragement, time after time.

I had a problem, too. Standing up at the bench in Steele for two or more hours of lab work was killing my back. So I started taking shortcuts.

One afternoon the assignment was to manufacture oxygen. The first thing was to bend some glass tubing into shape by heating it over a Bunsen burner. You were supposed to do it slowly so there would be no constriction of the tube. But slowly doesn't get you out of lab quickly, so I did it fast. Yes, there was constriction, but so what, I thought. It was still open somewhat.

Next we were to "dry" manganese dioxide by heating it over a watch glass. That seemed dumb and time-consuming to me (anybody could see that manganese dioxide was dry and not a liquid) so I cut that step out completely. I proceeded to mix my chemicals, insert rubber stoppers into the squeezed glass tubes, turn on the heat under the large test tube, and wait for the oxygen to bubble up into my water-filled upside-down collection bottles. I was ready to insert a glowing taper into my soon to be oxygen-rich bottles. I thought about how the taper would burst into flame with a wonderful "pop," proving that oxygen had displaced the water in the tubes.

I watched intently as the Bunsen burner heated the chemicals and bubbles of oxygen started to form. I was thrilled. For once, I thought, an experiment was actually coming out right.

Then I noticed something. At the bottom of the test tube there was just a suggestion of fire—inside the tube. Even I knew that was wrong. The flame grew bigger, working its way to the top of the test tube. BANG! The rubber stopper exploded across the room, fire shot out of the test tube like the tail of a comet, and there was a sound like a jet engine—which in fact it was.

Everyone in the lab hit the floor. Knowing it was my responsibility, I raised my head to bench level, carefully reached for the Bunsen burner, and turned it off. When the other students and I finally had the courage to stand up, I was shocked to see Professor Wolfenden rise from the floor opposite my place on the bench. He straightened up, brushed himself off, looked at me, and said, "Well, I guess we didn't get that one quite right, did we, Mr. Goss? Let's do it together this time and see if we can't do it right." And we did. I was surprised to find myself to be truly excited when I saw that glowing taper pop safely into flame, the way it was supposed to do. When we got that pop, the professor said, "Thank you, Mr. Goss," and left the bench.

I puzzled about that thank you for a long time. Why did he say that? After all, he had done the work, not me. Days later I figured it out. He had seen the pleasure come over my cynical face as we achieved something. Helping people was indeed his magnificent obsession.

I have remembered how to make oxygen for 45 years. I have also remembered the more important lesson Professor Wolfenden taught me that day: Life is not a shortcut. Life is about getting things right.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe Tasting

March 1995 By John R. Scotford Jr. '38 -

Cover Story

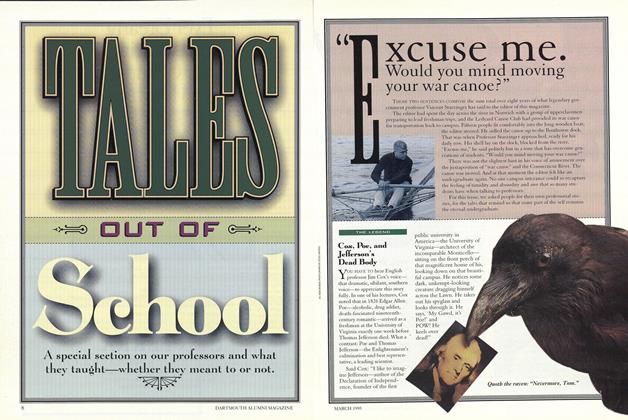

Cover StoryCox, Poe, and Jefferson's Dead Body

March 1995 By Peter Gilbert '76 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryDiseased With Poetry

March 1995 By Everett Wood '38 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryQuite Good

March 1995 By Abner Oakes IV '81 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryPoesis

March 1995 By David Bradley '38 -

Cover Story

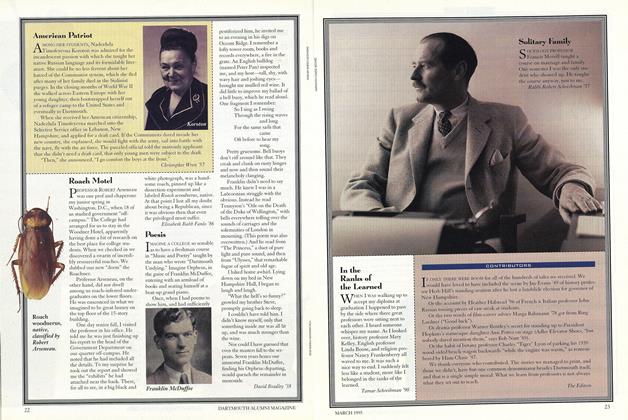

Cover StoryRousseau Cops an Exam

March 1995 By Philippa M. Guthrie '82

Donald Goss '53

Features

-

Feature

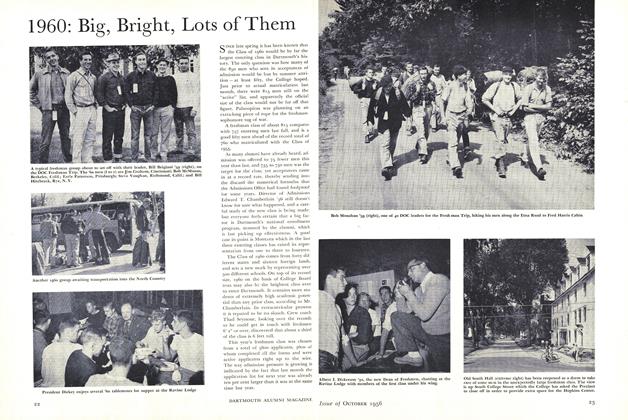

Feature1960: Big, Bright, Lots of Them

October 1956 -

Cover Story

Cover StorySEALED FILES

MARCH | APRIL 2014 -

Feature

FeatureEleazar Is Outdone

OCTOBER 1970 By Charles Jay Kershner -

Feature

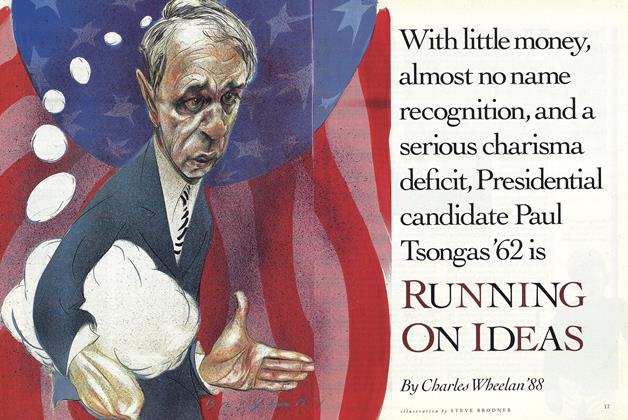

FeatureRUNNING ON IDEAS

OCTOBER 1991 By Charles Wheelan ’88 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryWhy Don't You Say Anything?"

APRIL 1997 By Davina Begaye Two Bears '90