Still a modernist in apostmodern world? Use our12-step program to change Your point of view

THERE IT IS. The word "postmodern." For a couple of decades now it has swirled through the academic world, taking hold in some fields, slipping by others. It was easy to ignore when it stayed within the ivory tower. But now post-modernism keeps cropping up in book reviews and op-ed es-says, and no one's saying exactly what it means. There's a reason for that, it turns out. "There's no single consensus definition-and that's one of the most postmodern things about it," says Dartmouth film studies professor Mark Williams. "It's an aesthetic, a critical methodology, and a philosophy."

Postmodernism is certainly more wily than the modernism that preceded it. Modernism stretched across art, architecture, literature, music, and various other fields, but shared the commonality of breaking with nineteenth-century tury traditions. Depending on the field, postmodernism may break with modernism, as in architecture (see Step 6), or take modernism to a further, if not new, level, as in literature (see Step 9).

But don't worry. You don't have to be a rocket scientist to understand postmodernism. In fact (see Step 7), it helps if you're not.

1. Rethink rationalism. Don't rely onb Reason, Science, Truth, and the steady march of Progress-all those Enlightenmentarticles of faith that underscore modernism. Why? Because, say postmodernists, nquestionning confidence in these ways of thinking about the world led to the kind of dogmatic notions that gave us World War II, auschwitz, the bomb. the Cold war, environmental degradaztion, and other man-made woes, As Darmouth studo art proessor Gerald Auten points out, "It's hard to learn about the twentieth entury and think fo it as progress.

2.Turn skeptical.

Postmodernists are suspicious of all "-isms." Some even eschew the term postmodernism on the grounds that "PoMo" is an approach, not a dogma. If you speak French you are in good PoMo company. The French go for PoMo, happily skewering-isms of all kinds. Psychiatrist Jacques Lacan, for example, put Freudianism under analysis. while cultural historian Michel Foucault deflected Marxism's certainty that history follows an inevitable trajectory. The French goverment even commissioned philosopher Jean Francois Lyotard to describe the postmodern con-dition. He pointed out, among other things, that the age of single interpretations of history and other top-down, unifying explanations of how the world works is over.

3. Hear your own accent.

Think everyone but you speaks with an accent? PoMo stresses that everyone brings an accent—a perspective—in thinking about the world. Failure to recognize our own perspectives indicates the extent to which we've bought into them. "Post-modernists dispute the idea of a single truth," says Lynn Higgins, Dartmouth professor of French and comparative literature. "All communication comes from somewhere—a speaker, a history, a moment, a time, and place. So postmodernists ask,' Where is the truth coming from? Who is the source? What is the historical frame?' And equally importantly they ask, 'Who benefits? Who is the truth for?"' Look, for example, at the idea of manifest destiny, says film studies professor Mark Williams. "Persecuted whites from Europe landed on this continent and through pluck moved west and turned great real estate into great power. That's a hell of a story. It doesn't talk about Native Americans, African Americans, or the environment." Post- modernists want to hear multiple truths.

4. Assume nothing.

Postmodernists see a lot of gray in between the black and white of polar Opposites, whether dealing with politics, gender, or the old distinction between high and low culture. Taking issue with structural anthropologist Claude Levi-Strauss (another Frenchman), who argued that all humans think in terms of "binary oppositions" like left and right or male and female, PoMo probes why people take some—but not all—concepts for granted. The paradox, says comp lit's Higgins: The more "natural" a concept seems, the more sure we can be that it rests on unexamined assumptions.

5. Crack the code.

"Postmodernism plays with codes to make them visible," says Higgins. Humans communicate in many ways: speech, body language, fashion, art, advertising blurbs. Sometimes the messages are loud and clear, sometimes they're hidden, and sometimes they clash. Postmodern artist Andres Serrano clashed codes in his controversial construction Piss Christ, says studio art professor Gerald Auten. "Serrano placed a plastic Christ in a jar filled with urine. On formal terms alone it was a beautiful composition. "Yet the title causes most people to revile the image. "In calling it Piss Christ he was praying off the Victorian idea of piss being unspeakable and disgusting. If Serrano had called the same composition AmberChrist we'd all love it."

6. Break out of the box.

modern architects believe that "less is more," but pioneering postmodern architect Robert Venturi the man behind the Thayer School's Cummings Hall and the new Berry Library, thinks that "less is a bore." Rejecting modern architects devotion to the box ("They thought modern architecture would improve lives, even alleviate crime," says Dartmouth architectural history professor Marlene Heck), Venturi brought back columns, capitals, color, moldings, and trim in playful nods to history and decoration. "Think of postmodern architecture as a building wearing a hat," says studio art prof Gerald Auten. But easy come, easy go. PoMo architecture is already evolving into new forms (and -isms): neomodernism (resurrecting modernism's boxes but not its delusions about improving humanity) and decontructivism (fractured, fragmented, and juxtaposed structures like Frank Gehry's new Bilbao Museum.) "Postmodernism is dead," declares Heck. "It lost its authority in the 1980s." Well, not completely, she concedes. "It hangs on in Kmart's tarted-up storefronts." Modern architects believe that "less

7. Deface facts.

Postmodernists question the authority of science. "Postmodernism views science as a cultural activity like any other," says history of science professor Richard Kremer. "It sees science as a stage where people make claims about truth. Like literature, both are posturings. PoMo sees nature as the invention of scientists." But how about the objective reality of facts? "If they're so objective," says comp lit's Higgins, "how come yesterday's fact is today's joke?" Postmodernists emphasize that so-called facts come from somewhere—from someone—and may be wrong. Like many scientists, physics professor John Thorstensen doesn't share PoMo's worries about the invention of facts. "Everyone knows what a fact is," he bristles. "Let's get on with the work." There's definitely a place for this kind of thinking in a PoMo world. As government and Native American studies professor Dale Turner says, "I want my bridges to be built by empiricists."

8. Watch TV.

"Television is PoMo par excellence," says film prof Mark Williams. "Everyone deciphers TV, but not in the same way." Cable has made TV even more PoMo, as the proliferation of channels increasingly eclipses the big three networks and the picture of national coherence they once broadcast. If you're ever in doubt about postmodernist Jean Baudrillard's observation that contemporary society is so overloaded with information that meaning has become meaningless, spend some time channel-surfing. And, says Williams, if you want to see what PoMo aesthetics look like, watch MTV.

9. Play with narrative.

PoMo fiddles with our expectations about storytelling, extending modernism's groundbreaking techniques (such as James Joyce's stream-of-consciousness writing) by several notches. Take "hyperfiction," interactive computer stories that invite readers to choose between multiple strands of stories, go off on tangents, piece stories together by accumulating bits and pieces of information, or revel in the fragments. "Hyperfiction breaks out of linear narrative," says English professor Brenda Silver, who teaches a hyperfiction course (taken mainly by guys). "It foregrounds all the things we take for granted when we readsuch as context, sequence, clear referents for pronouns, tables of contents, page numbers, closure. It's an extention of how we experience life, which isn't linear." (To try some hyperfiction netsurf to .)

PoMo movies similarly play with our expectations of narrative. "At the end of Quentin Tarantino's Pulp Fiction you're forced to realize the narrative wasn't real time; it might have been a thought," says comp lit's Higgins. "David Lynch's BlueVelvet pushes the natural so far it's not natural anymore."

The point of all this narrative play? To help us see that, as Higgins says, "People construct stories and stories construct people." Or as Silver puts it, "Life is a narrative."

10. Chuck "reality."

Reality isn't just out there. People make itup, say the postmodernists. "People construct all notions of reality— in life and in art," says Higgins. "Postmodernists try to analyze how ideas are constructed by deconstructing them—breaking them down into their component pieces. The process shows the lack of coherence in what we take to be natural, logical, rational, and true."

11. Listen to the music.

Postmodern music plays with musical conventions. There's no hard-and-fast line between modern and postmodern music, according to composer and music professor Christian Wolff, who studied music under modern composer John Cage and considers himself a modernist. "To me postmodern means dispersal and heterogeneity," he says. His own music draws on such sources as Woody Guthrie and the music of the Wobblies—the International Workers of the World. His music also departs from the expected. "I leave much of the music to the musician, even choices of notes," he says. "I might tell them to play at the end of the last sound that they hear—but sometimes the instrument isn't specified, or the pitch isn't specified. Or, play until two sounds go by and at the beginning of the third, stop. Or, play a note, then change the color of the sound twice—as opposed to the usual kind of direction, such as 'sing an E-flat for two beats.' It shifts the area of focus from pitch to duration and color."

Sure sounds PoMo. Well, he considers, maybe it is.

12. Approach knowledge humbly.

Instead of assuming that we know what we know, PoMo calls for double-checking methodologies and assumptions. "We need to acknowledge the questions we're begging," says English professor Tom Luxon "Every time we use a convention, we forget about the assumption." But keep PoMo in perspective, he urges. "There's kind of a Zen to it. If you're constantly attending to it, you're paralyzed. If you never attend to it you're dogmatic. You need to go in and out of it." The bottom line, he says: "Approach everything thing with humility."

KAREN endicott is senior editor at this magazine.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

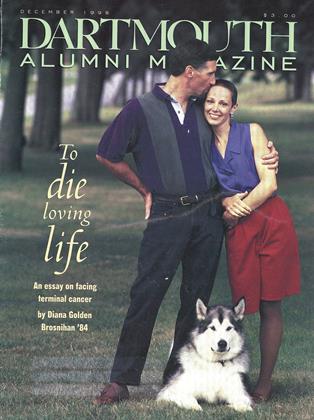

Cover StoryTo die loving life

December 1998 By Diana Golden Brosnihan '84 -

Feature

FeatureHere by the Fire

December 1998 By James Zug '91 -

Feature

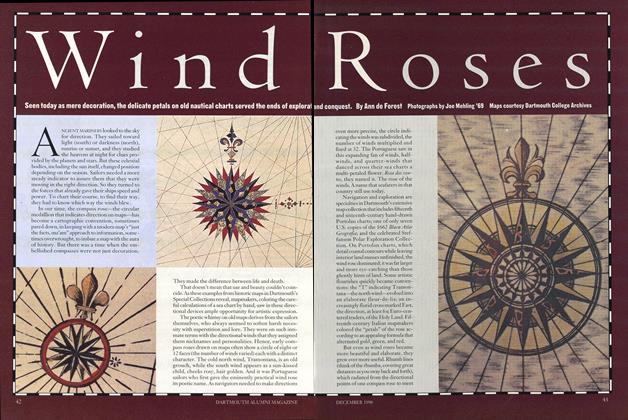

FeatureWind Roses

December 1998 By Ann de Forest -

Article

ArticlePrediction Fiction

December 1998 By Christine Schultz -

Class Notes

Class Notes1997

December 1998 By Abby Klingbeil -

Article

ArticleLooking for Frost

December 1998 By Noel Perrin

Karen Endicott

-

Article

ArticlePatient Talk

September 1993 By Karen Endicott -

Article

ArticleArt in a Box

Winter 1993 By Karen Endicott -

Feature

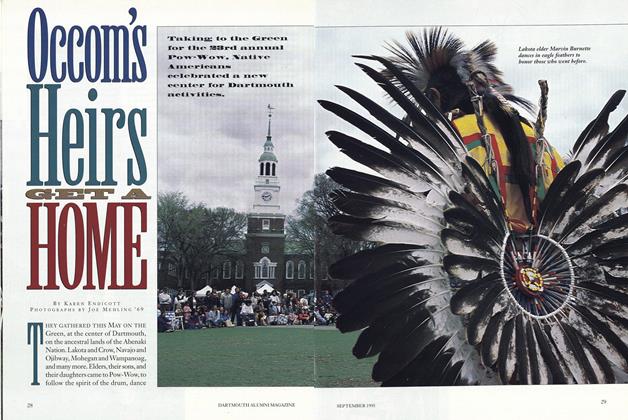

FeatureOccom's Heirs Get a Home

September 1995 By Karen Endicott -

Interview

InterviewDartmouth on the Brain: Green Research and Gray Matter

SEPTEMBER 1999 By Karen Endicott -

Interview

Interview"A Diversity of Ideas"

July/Aug 2003 By Karen Endicott -

Article

ArticleWHAT HAPPENED TO THE DEMOCRATS?

APRIL 1989 By Robert Arseneau, Karen Endicott

Features

-

Feature

FeatureNous Étudiants à l'Étranger

FEBRUARY 1967 -

Feature

FeatureYOU CAN LIVE WHERE FOGHAT SANG

APRIL 1989 -

Feature

FeatureJUST LIKE THE REST OF US

November 1976 By A. KELLEY FEAD -

Feature

FeatureAlumni News

Jan/Feb 2008 By Cameron Myler '92 -

Feature

FeatureNotebook

July/August 2007 By JOHN SHERMAN, JOHN SHERMAN -

Feature

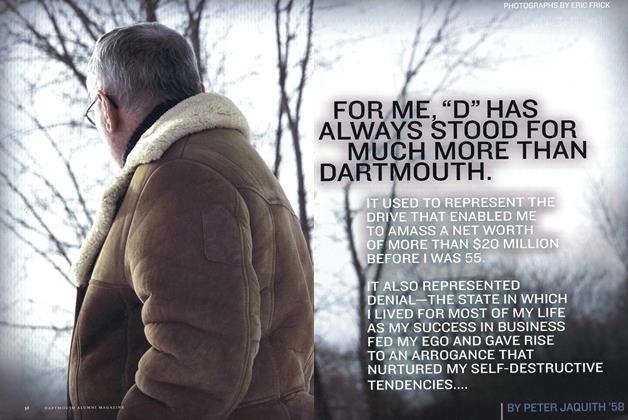

Feature“D” is for Denial

Mar/Apr 2006 By PETER JAQUITH ’58