Just one thing determines whether you have the stuff to be a collector: Not money, taste, or an art-history education, but the willingness to be dragged by the nostrils on the whiff of Something Great.

JOHN FRIEDE '60 is a civilized man, but civility has its limits when it comes to certain life and-death matters, such as the 2,000 objects of Oceanic art that fill his Westchester County home. Ask, very politely, which item he might choose if he could have only one, and Friede mutters darkly. Engage in hypothetical discussions of keeping pieces in storage, and he threatens "burials under slate."

Nearby stands a seven-foot-tall, centuries-old headhunting spirit from New Guinea's Yuat River, massive shoulders hunched and eyes bulging from a powerful, sloping head. Friede declares it "one of the half-dozen best pieces of New Guinea art in the world." He nods to the piece and—did I see this—lifts his glass. There seems a moment of mutual kinship, and in that moment it becomes clear that Friede might possibly take—or more likely, givea bullet for this guy.

As between genius and insanity, Friede has crossed the line between those who buy art and those who collect. Art buyers admire a piece, deliberate a bit, and then rationalize that yes, this painting's blend of yellow and mauve suits the new carpeting. Collectors, on the other hand, say things like, "When I saw that painting it just dropped me to my knees." They trace a hand-crafted tabletop with wondering fingertips, seeing "jewel-like drops of water" on the surface. They wait 20 years for the right Richard Miller oil or nineteenth- century Iranian rug, or travel to Iceland to see what Richard Serra has done with sculpture.

In short, they occupy a world where people and objects assume a hierarchy not found in the natural order. Dealer and collector Robert Dance '77 declares collecting a "pathology." Says Friede, upon exiting his greenhouse collection of exotic plants and orchids, "Hobbyists suffer from compulsive minds." Collector Roger Arvid Anderson '68, some of whose Renaissance bronzes are in the Hood, defines collecting as a primal, ancient urge. "I would relate it to the hunting instinct," he says. "A lot of collectors in this way displace that elemental need to go out and find game."

True collectors do not possess but pursue. Favorite pieces accompany stories of tracking, discovery, flushing, bagging. You hear, for instance, how American art acquirer Thomas Davies '62 found a blackened something in a box of charred frames at a street fair. Three dollars to buy, $50 to clean, and he owned a brillianttoned Daniel Putnam Brindley seascape. Friede unearthed an important object in a box ofjumble in England because he recognized the scrawl of a nineteenth-century dealer. Fine-art dealer Jeffrey Brown '61 spotted an unidentified John LaFarge at a New England auction.

Such tales make you believe anyone can become a collector of note, and, strictly speaking, anyone can. It is not necessary to be wealthy to begin collecting, given that serious collecting will supersede wealth anyway. ("It doesn't matter how much money you've got," says Mickey Baten '56, a collector of eighteenth-, nineteenth-, and twentieth-century Americana. "You're always going to be poor.") Nor is it strictly necessary to have taste, leisure time, or an art-history education.

What is necessary is an apparent willingness to be dragged by the nostrils on the whiff of Something Great. By and large, collectors are not halfway people, cruising the occasional gallery or tag sale. They live and breathe the pursuit. To collect, "you have to have a vital interest in collecting," says Richard Rush '37, an expert in Old Masters. "Otherwise you won't spend the time becoming familiar with the characteristics of the artist. I get all these catalogs and I have to keep up. What's going to drive me? It's going to be an interest in this."

Collecting is work. The urge to collect may be largely innate ("Show me a kid who only wants one baseball card," says Brown), but the art of collecting involves more nurture than nature. Poor collections

are pictures with names purchased by checklist. Good collections have a shape, refinement, and energy. Walk among Friede's pieces, and you expect them to shake and dance as soon as you leave the room. "I don't collect objects at all," Friede likes to say. "This is a symphony."

To begin the pursuit, one needs collected wisdom. Herewith:

BEGIN ANYWHERE.

Collecting is an evolutionary compulsion. Like making sauce or casting for trout, true collecting usually occurs somewhere tar afield from the starting point.

Friede, for instance, began with seashells as a kid, moved to African art, and was stopped cold the day he saw a warehouse full of New Guinea sculpture. He felt the way he felt when he first saw his wife. Having immersed himself in drawing, theater, poetry, travel, and collage, Anderson bought his first bronze in 1972, a Chinese bell in the archaic style. "People with an architecture sensibility love the feeling of mass," he says of bronze. "You watch the light reveal the surfaces...."

Collectors begin where they are attracted, led by instinct, exposure, or childhood memory. One day a "right" piece beckons, the scales fall, and you're off to the races. Dance, for instance, chanced on a photograph of Greta Garbo by Clarence Bull. A slight furrow in her brow etched vulnerability onto her distinctive ennui. Dance was a goner. He now has 350 early Hollywood photographs. Says he: "One thing leads to another."

ACQUIRE MENTORS.

In his early 20s, Davies shot pool with crotchety artists at the Salmagundi Club, a New York City artists' group, discussing the Cape Ann School between matches. Dance grew friendly with an older collector and

connoisseur, Paul Magnel, who would challenge him at galleries: "What's the best thing in this room? You've got eyes, haven't you?"

Behind every new collector is a better pair of eyes—a collector, artist, or more of ten, dealer. "This is very important," says Anderson: "to find mentors whose judgment you feel matches yours; who will be very decisive about what you should look for and buy." What follows is symbiosis. At this point, print collector Bill Clark '42 knows his dealers well enough to merge their visions. "One was in Paris last year, saw a print in a window, and said, 'That's Bill Clark,"' Clark says. It was.

IF YOU'RE GOING TO INVEST...PICK STOCKS.

Richard Rush '37 has acquired a Titian, a Palladian villa, a Rembrandt, a Veronese, and scores of other Old Masters; has written more than 600 articles and penned a dozen book on collecting; and has never lost money on a work of art. Rush also has brilliant timing, a highly evolved eye, and an artist spouse who can spot a Rubens by the particular mix of paints used in the subject's eye.

Hence, he is the exception to this rule: If you're going to collect art, don't collect pragmatically. Buy because you must. "A passionate collector," says Brown, "is one who knows a second-rate object brings $5,000 at a public sale, but sees a great one for $30,000 and says 'Oh, God, that's wonderful.' It's the viscera overruling the head."

Buying art as a "deal" or investment—unless you are extraordinarily savvy—usually leads to second-rate objects. If a piece doesn't jolt you, it's not likely to jolt anyone else. "You buy these things not because you think they're a good buy," says Baten. "So what if it doesn't go anywhere [in value] as long as it says something to you? Art is only the emotion one gets from looking at an object. If it doesn't hit you right away it's not art for you."

MAKE MISTAKES.

"You have to," says contemporary art collector and patron Wynn Kramarsky, parent of a Dartmouth '92. "If you collect and don't make mistakes, then the collection is

very boring, or you're getting very bad advice."

Mistakes cut two ways. Incaution—likely, a bout of auction fever—results in "What was I thinking?" when the piece in question is examined in the cold light of one's bank account. Overcaution leads to woe and worry about the stuff you didn't buy.

Mistakes train the eye; they dislodge preconceived ideas about what you like and what you want to live with. They make for better picking next time. "You start out with trepidation as to your judgment," says Cal Palitz '52, an extremely market-sawy collector of American paintings, glass, silver, and furniture. "As time moves on you start to validate your judgment and your tastes mature, and you start to like the finer things."

LEARN IT.

Though collectors occasionally pull rabbits from hats, dumb luck does not grant favor. Picking a masterpiece is not like picking a lotto number. "Opportunities don't come to unknowledgeable people," says Davies. "Opportunities come because you know enough to spot them. Nothing is a substitute for knowledge."

Friede has read every book published on New Guinea art, including French and excepting high German. Select any of his 2,000 objects, and he can recite provenance, date, significance, region, and names of collectors with matching objects. Kramarsky visits scores of new artists annually and can instantly evaluate their place in the art-history pantheon. Collecting is "educated passion," he says. "If you look at a Ryman, you had better have looked at Rembrandt and Cezanne and Mondrian."

Collectors read. They attend shows, lectures, and galleries. They network with others. They pore through catalogs in bed. "For the collector who wishes to dig in with both feet," says Jack Huber '63, who collects American works on paper, "there's a lot of sweat equity involved."

IT HELPS TO HAVE AN EYE.

Like perfect pitch, a good eye sifts good from great, knows genius from mere beauty. Perfect pitch is rare. So is a good eye. "People feel because they have eyes they can make an aesthetic decision," says Dance, "and that's not always true."

Purists believe that "knowing" if you have an eye is akin to "knowing" whether you're in love. If you have to ask, you don't. Which brings us back to education. A well-trained eye, in most cases, will compensate for instinct; visual sensitivity—the ability to "see a fine taper, the pattern of a surface, the way a painter catches a slant of light," as Hood Museum director Timothy Rub puts it will supply the rest.

To a certain extent, anyway. Without an eye, one can always have a good collection. "The next level," as Baten notes, "is to recognize greatness and be touched by it and not doubt your response to it." Call it "eye" level, if you will.

IT REALLY HELPS TO HAVE MONEY.

Rule of thumb: Buy the best you can afford and still keep the IRA intact. Pick top quality and top condition. Better to buy the best work of a secondary artist, or in a secondary medium, than the secondary work of a top artist. If you shop for flea-market prices, that's pretty much what you get. "Buy on the cheap," says Dance, "and you have a collection that's second rate."

"Some people are bargain-oriented," says Anderson. "My idea of a bargain is to be the first person offered a great object."

LET IT GO.

Collections are organic. There are those people who must find the 72 matching pieces of a silver set, or every Trifari brooch, or every Partridge Family album, but they're not collectors. They're hoarders. Good collectors assess their objects continually for pleasure. As tastes mature and emerge, as new objects come onto the market or new styles begin to curry favor, collectors cull what pleases them less in order to acquire what pleases them more. As Baten puts it, "Satisfaction breeds stagnation."

Besides, culling creates funds. As a collection plateaus, selling—provided you've collected well—creates the financial leverage to move to the next level. "People who are smitten develop and sell work to be able to buy work," Davies says.

PLAN FOR POSTERITY.

Unlike, say, humans, works of art continue to be that way for a very long time. All collectors must decide how pieces will be dispersed and disposed. If family isn't the final destination, museums generally are—which explains why the overwhelming majority of the 60,000 objects at the Hood Museum (only about one percent of which are on permanent display) have been acquired through donations, either through alumni or friends of the College.

Even to visit these works, some of which, like Frederic Remington's Shotgun Hospitality, were granted a century ago, is to induce humility. Humans erode; great collections go on.

As a collector of art, "you're only a trustee," says Palitz. "If something is beautiful and lovely and important, it goes on way after you. You don't own anything. You lease it. You pay to have the pleasure of it during your lifetime."

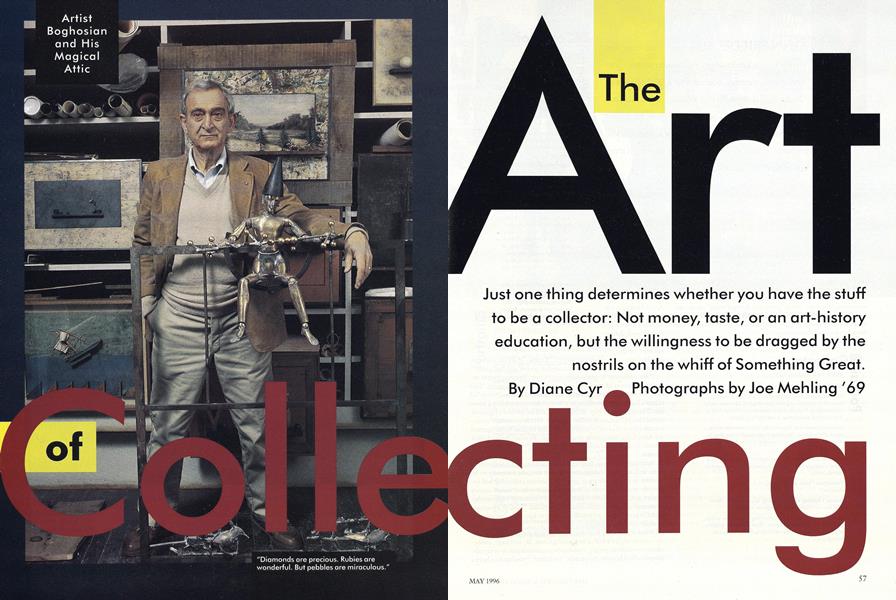

Artist Boghosian and His Magical Attic

The Friedes in Their Living Museum

Director Rub in His Hood

Dealer Brown and Art that Grabbed

Acquirer Davies with His Paintings

"Diamonds are precious. Rubies are wonderful. But pebbles are miraculous."

Portrail of a Collector WYNN KRAMARSKY DARTMOUTH PARENT '92 Environment: Intellectual urban loft. Spare, meticulous office space hung with drawings by Ellsworth Kelly, Jasper Johns, Richard Serra, and others. Friend Sol LeWitt painted geometries in the skylight space. Seminal moment: Discovering the minimalist movement of the Sixties. "It spoke to me much more clearly, and with impact. It said to me that you've got to do most of the work." Signs of addiction: Visiting Iceland to view a Richard Serra sculpture that relates to a Serra drawing that Kramarsky owns. Favorites: "Such an ugly thing to do. How do I choose?" Doesn't bother with..."Facility. Superficiality. Work that doesn't have much thought or muscle." Collecting philosophy: Supporting young new artists; granting free exhibition space. "Part of this is a question of social conscience. It's not to help the artist, but to help the art."

Portrait of a Collector VARUJAN BOGHOSIAN ARTIST AND STUDIO ART PROFESSOR Environment: Magical attic. Carved heads, bronze birds, patinaed blocks, glass spheres, ceramic pipe stems, tiny treasures collected in still, small, numberless piles. Seminal moment: Ongoing. "It's natural to pick up things, hold things that are your own." Signs of addiction: Buyer's remorse over mustacheshaped mustache combs. "Somebody had 50 and I only bought three or four, like a fool." Favorites: Palette knife with a sumptuous curve. Italian doll heads with waves of carved hair. Student's painting palette smeared with blue and gold. Anchor blocks. A squashed paint tube, presented on a black velvet pillow. "Look at that. Isn't that fantastic?" Doesn't bother with...the unaesthetic. Buying philosophy: "Diamonds are precious. Rubies are wonderful. But pebbles are miraculous."

"I don't collect objects at all. This is a symphony."

Portrait of a Collector JOHN FRIEDE '60 Environment: Living museum. Transported from jungles, shrines, and riverbeds, armies of ancient, primal, Oceanic sculptures practi cally charge off the walls of these high, formal rooms. Seminal moment: Spotting 90 pieces of New Guinea art in a collector's warehouse. "There is no art in the world that speaks to me with the same degree of personal authenticity. It is the art of the first people." Signs of addiction: Awaiting a software program that will enable translation of German texts on New Guinea. Favorites: Objects for initiation rites; a shield of undulating carved faces in oranges, browns, and whites. "As fine a representation of Baroque art as I have ever seen in my entire life. Look at this thing. It's not going to stop." Doesn't bother with...Contemporary art. "There's no restraints. It's like running in a place with no gravity. There's no aerobic exercise." Collecting philosophy: "If you can't afford to play, get off the field. Second-best objects are unsatisfying because they lack content."

A collector can "see a fine taper,the pattern of a surface, the way apainter catches a slant of light."

Portrait of a Collector TIMOTHY RUB DIRECTOR, HOOD MUSEUM Environment: A clean, well-lighted space. Well-ordered congruency of many art styles and cultures, from Eastern antiquities to Carravagisti to nineteenth-century Luminists to Sol LeWitt. Seminal moments: Acquiring two important American genre works and a Willard L. Metcalf Impressionist work, The First Thaw.Signs of addiction: Continual lobbying has more than quadrupled annual income from endowments. Favorites: Joan Miro print; Ed Ruscha's Standard Station, Amarillo, Texas; portrait of alumnus George Ticknor 1807 by Thomas Sully—and that colossal Assyrian relief. Doesn't bother with...objects lacking an art-historical purpose or teaching value. Collecting philosophy: Establish long-term loans from other museums. Increase endowment. Fill gaps in nineteenth-century European painting, particularly Impressionism and post-Impressionism, Barbizon and Romantic schools. "And that's just painting."

Portrait of a Collector JEFFREY BROWN '61 Environment: Warmly offbeat. Luminous nineteenth-century landscapes vibrate off cinnabar and teal walls; toys (from six-year-old son Binney) mix with polished, quirky, and eccentrically modern crafted studio furniture. (Brown and wife Kathryn Corbin sit on the board of the Boston Society of Arts and Crafts.) Seminal moment: While a curator in an upstate New York museum, worked with a director impassioned with American art. "These are enthusiasms you catch." Signs of addiction: Puttered in small motorboat ten miles up the Massachu setts coast to locate a spot depicted in an A.T. Bricher seascape. Favorites: Moths in the Moon, by Elihu Vedder, depicting "a level of mystery and particular poetry and that idiosyncratic quirky thing that speaks to both of US." Doesn't bother with...the loud and obyious. "I respond to the poetic much more than to sock-it-to-you." Collecting philosophy: Acquiring objects that "grab you so hard that they don't let you go."

"Show me a kid who only wants one baseball card."

Portrait of a Collector CAL PALITZ '52 Environment: Museum-appointed luxury. Sherry glasses from the White House, shelves of early Steuben eighteenth- and nineteenth-century formal American furniture, Pisarro, Benton, American Impressionists on hand-stippled walls. Seminal moment: Acquired a Townson table in 1954 while living in Newport. Cost: $375, "over a month's wages, pretax." Signs of addiction: Financially backing dealers during the past few decades in order to acquire. "To validate my judgment, I have to be a seller." Favorites: The Townson table. Otherwise, it's all open to sale. "Then we can replace them with more things we'll love." Doesn't bother with...the unpleasant. "When I see a couple of plates stuck on a canvas, I've got a problem with that." Buying philosophy: "Most collectors fall in love and then buy. We buy and fall in love. We find that keeps the costs down."

Portrait of a Collector THOMAS DAVIES '62 Environment: Paintings! Landscapes, figure paintings, genre works, still lifes, Western motifs, and numerous other American works wallpaper each room. Seminal moment: Meeting with Digby Chandler, lay member at the Salmagundi Club, who offered Davies the pick of his own collection. "It was the first time I was confronted with the idea that either you're serious, or you're a dabbler." Signs of addiction: While living in Hong Kong,pplaning,nning, hanging, and writing a catalog for a 150-piece exhibit on the history of American painting. Favorites: Richard Miller American Impressionism; Gloucester seascapes; Hard Times, a black subject portrait by J.G. Brown. "You'd have to break my arm to get that out of the house." Doesn't bother with...Abstract or early American portraiture. Collecting philosophy: "The old-fashioned Rolodex is my best friend."

"Opportunities come because you know enough to spot them. "

Writer DIANE CYR lives tastefully in Connecticut.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryWha is There to Teach About Art?

May 1996 By Rebecca Bailey -

Feature

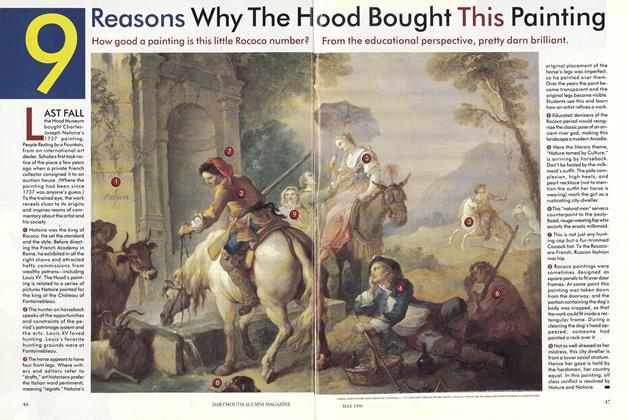

FeatureA Mini-Seminar On Two Hood Pieces

May 1996 -

Feature

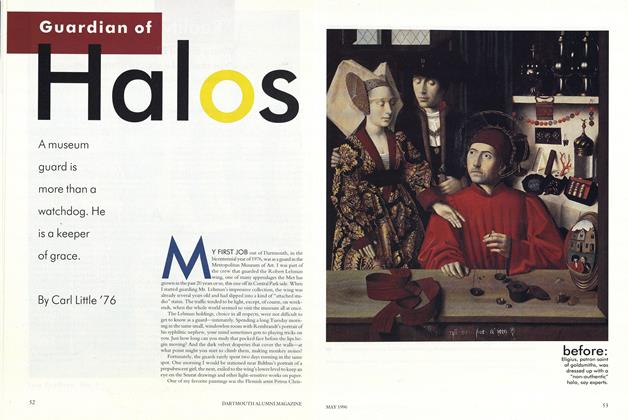

FeatureGuardian of Halos

May 1996 By Carl Little '76 -

Feature

Feature9 Reasons Why the Hood Bought This Painting

May 1996 -

Article

ArticleVisions of the Ancestors

May 1996 By Karen Endicott -

Article

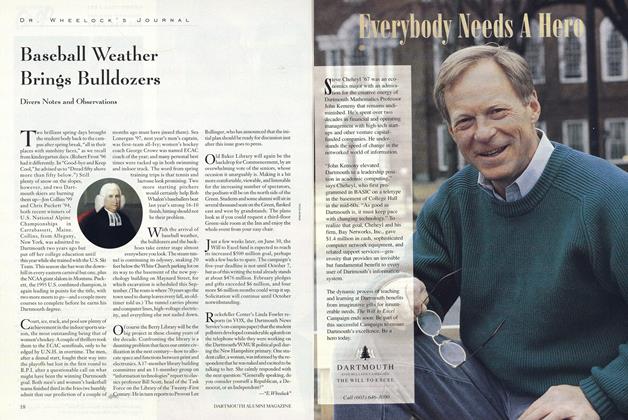

ArticleBaseball Weather Brings Bulldozers

May 1996 By "E. Wheelock"

Diane Cyr

Features

-

Feature

FeatureDartmouth on Capitol Hill

JANUARY 1965 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryJohn P. Collier '72, Th'77

March 1993 -

Feature

FeatureBob Graham '40, Newsman

JUNE/JULY 1984 By Howard Coffin -

Feature

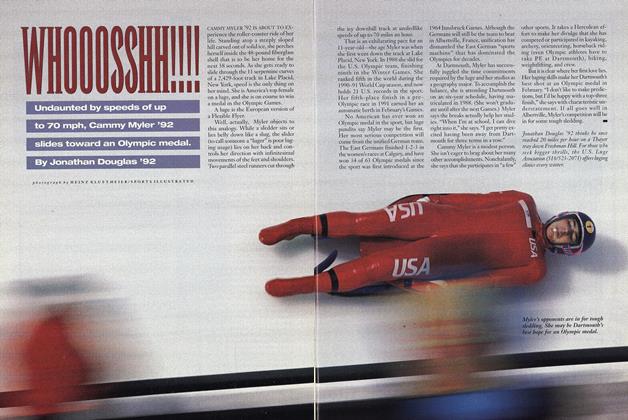

FeatureWHOOOSSHH!!!!

December 1991 By Jonathan Douglas '92 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe Unknown and Unsung Undergraduate Days of Stephen Colbert ’86

July/August 2008 By Robert Sullivan ’75 -

Feature

FeatureThe Second Emancipation

JULY 1963 By THE REV. JAMES H. ROBINSON, D.D. '63