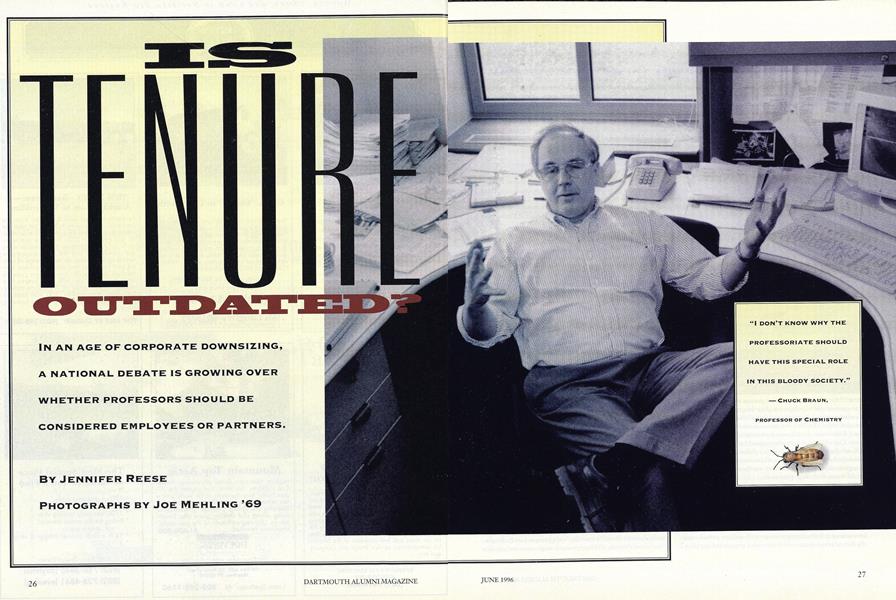

IN AN AGE OF CORPORATE DOWNSIZING, A NATIONAL DEBATE IS GROWING OVER WHETHER PROFESSORS SHOULD BE CONSIDERED EMPLOYEES OR PARTNERS.

Daniel Webster, class of 1801 Trustees of Dartmouth College v. Woodward, 1818

In 1816, the state of New Hampshire decided to meddle in the affairs of Dartmouth College. The legislature appointed nine new trustees and ruled that the decisions of the previously independent Dartmouth board would thereafter be scrutinized by a public board of overseers. What a mistake. The College Trustees were furious. With the fiery Daniel Webster, class of 1801, as their advocate, they took their case to the Supreme Court and won back their independence.

The case still makes the legal textbooks because of the precedent it set in contract law. But it is also interesting because it contains some of the earliest arguments for tenure in America. If colleges were to become places where scholars were answerable to politicians, Webster argued, "learned men will be deterred from devoting themselves to the service of such institutions.... Colleges and halls will be deserted by all better spirits, and become a theatre for the contention of politics; party and faction will be cherished in the places consecrated to piety and learning."

Chief Justice John Marshall completely ignored this line of argument. But 80 years later, Webster's oration would have gotten a more attentive hearing. Academic freedom was a hot topic by the turn of the century, when the president of Stanford University, David Starr Jordan, fired an economics professor named Edward Ross. Although Ross's scholarship was respected and his teaching reportedly excellent, Jane Stanford, then the school's sole trustee, didn't like his opinions, which included both admiration for the socialist Eugene Debs and a distaste for Asian immigrants. She wrote in a letter to Jordan, "Professor Ross cannot be trusted, and he should go." So he went. Seven other faculty members left in protest. Historians have tended to present the Stanford case as a clear-cut example of politics invading the groves of the academy, of a scholar wrongfully terminated for his leftist views. In fact, there is evidence that Mrs. Stanford was more disturbed by Ross's racial biases. Either way, the case was a watershed in the history of education. One of the professors who resigned from Stanford at the time of Ross's departure, Arthur Lovejoy, a philosopher, went on to cofound the American Association of University Professors (AAUP), an organization whose raison d'être was the establishment of a system of tenure for college professors.

Whether you approve or disapprove of tenure today, it is hard to argue with its original mission: to ensure that American scholars would have freedom to seek the truth and speak their minds, without fearing for their livelihoods. Under the system created by the AAUP in 1915 (instituted at Dartmouth in 1917) and refined over several decades, professors who met a school's requirements for teaching and scholarship during a probationary period—usually five to seven years—were thereafter guaranteed continued employment, no matter if they disagreed with the views of trustees, administrators, or their own colleagues. A tenured professor could be terminated for three reasons: severe financial problems at the institution, provable incompetence, or the dropping of a discipline. School after school across the country adopted tenure, as admin-recognized the need to protect their institutions from the whims of the public. Today the system is in place at almost every college in America.

But the system is coming under increasing fire. With roots in the medieval university, tenure's underlying principles are nothing new. Nor is the fierce controversy surrounding them. The history of academia is one long struggle between scholars who want to govern themselves, and the outside world, which wants to hold them accountable. In the thirteenth century, after the chancellor of the Cathedral Church of Notre Dame insisted on his right to hire and fire scholars, the faculty of the University of Paris protested and ultimately won a form of tenure whereby "masters" could no longer be dismissed by an outsider. As retired Columbia University historian Walter Metzger writes, "In the chronicles of old Oxford and Paris, the act of removing a master is commonly referred to as a 'privation,' sometimes as a 'banishment,' but not as a 'discharge' or 'dismissal.'" The terminology makes clear that a master was not so much an employee of the university as a member of a brotherhood. This describes almost perfectly the status of tenured professors today—something plenty of people would like to change.

These days it is budget-conscious lawmakers and administrators who want more of a say in the staffing of universities. In the last five years legislators in Arkansas and Florida, among other states, have tried to rein in education spending by introducing bills abolishing tenure at public institutions. None has passed. A few private schools, such as Bennington College, have been more successful. Charged with closing a $1 million deficit, reducing tuition, and increasing enrollment, in 1994 Bennington president Elizabeth Coleman fired more than 20 tenured faculty members and effectively eradicated the school's system of tenure.

What happened at Bennington won't become widespread any time soon. First of all, it is hard to pull off. Three years ago, the president of San Diego State tried to balance his budget by eliminating 100 tenured professors. Like their thirteenth-century French counterparts, the faculty rose in revolt, the legislature came up with funds, and the president backed down. Tenure is also safe, for the moment, at nationally known universities like Dartmouth. "Nobody at this institution is putting on the table the question of whether tenure should continue," says provost Lee Bollinger. When asked if increased budget pressures might eventually lead to a rethinking of tenure, College President James O. Freedman replies flatly: "It wouldn't even be on the list of options."

For purely practical reasons it would be disastrous for a school like Dartmouth to eliminate tenure. Last year Dartmouth topped the "best teaching" list in U.S. News & World Report's annual college rankings. The faculty that helped put it there could easily find work elsewhere. Although there is no shortage of applicants, the competition for the stars is keen. If nothing else, tenure is a powerful recruiting tool. "Dartmouth could do away with tenure tomorrow," says chemistry professor Chuck Braun, who has three times served on the committee that makes tenure decisions. "But faculty hiring would stop. We're part of the system. We would end up with a miserable group of applicants.'

Elsewhere within "the system," however, academia is starting to discuss a change in the tenure policy. In 1992 incoming Stanford president Gerhard Casper told a group of economists that, to get the budget under control, the elimination of tenure is something we may have to consider in the long run.

Tenure has always had its detractors. Why are they getting a wider hearing today? "There is a sense that these jobs are cushy, and that professors have abandoned a sense of professionalism by giving in to political desires," says Bollinger. The idea is, you've got to be more competitive. One has a feeling these forces are coming down on higher education.

Tenure has an ever-worsening image. To the public, professors appear to be unproductive and overindulged. Scores of white-collar workers are getting laid off," says Richard Chait, professor of higher education at the University of Maryland and coauthor of Beyond Traditional Tenure. "Then every time a few tenured faculty members are dismissed, we make a fuss, it gets in the paper, and the public says: this is nonsense." Dartmouth's Chuck Braun says something similar. "I don't know why the professoriate should have this special role in this bloody society. I can't justify tenure based on imagining that the president will make a decree that will put us all in jail. Science isn't controversial today. I feel guilty when I see all these 50-year-old middle managers at AT&T laid off."

On purely economic grounds, it is hard to make the case for tenure. Professors don't deserve financial security any more than anyone else. Moreover, there is currently no need for incentives to draw people into academic careers. The AAUP says that the second goal of tenure, after safeguarding academic freedom, is to offer "a sufficient degree of economic security to make the profession attractive to men and women of ability." But the job market today is glutted with would-be professors. Dartmouth receives hundreds of applications for every opening.

Compounding tenure's image problem is the longstanding notion that it makes academics lazy. Nationally, tenured professors spend roughly ten hours a week in the classroom and earn, on average, $65,400 for a nine-month year. At Dartmouth an associate professor averages around $54,800 and a full professor pulls in $80,500. Tenure, therefore, offers a comfortable salary, flexible hours, summer vacations, and little risk of being fired. There would seem to be plenty of room for slacking off. "I'm 37," says Susan Ackerman '80, an assistant professor of religion, who is under consideration for tenure this year. "Presumably I could obtain tenure at 37 and continue to teach oft of the same yellowing pieces of paper for the next 30 years. I don't think that's a huge problem here, but it's a danger in the system at large."

Nonetheless, studies show that most professors nationwide are not teaching off yellowing pieces of paper: An AAUP survey found that professors today put in, on average, more than 50 hours a week—up about ten hours from what they worked in the 19705. They also seem to be spending more time dealing with budget crises and completing paperwork required by new regulations. And at Dartmouth, at least, professional pride seems to be a powerful motivator. "We all have our egos and identities on the line," says Margaret Darrow, associate professor of history. "The threat of having our job taken away isn't what makes Rabbit run here."

But whether professors work less, more, or about the same as everyone else is irrelevant. Money is tight. And in what profession do people not have to deal with market forces? In recent years, states have cut back funding for public colleges and enrollments are down at private schools. This has created an ironic situation: Rather than safeguarding the unfettered flow of knowledge, tenure increasingly appears to safeguard the jobs of middle-aged and elderly academics. Under the current budgetary situation at Dartmouth, says Bollinger, " We're able to continue to do more or less what we've been doing, but we have very little money to do anything new. It's frustrating. It can lead to feelings of stagnation." Schools no longer have the resources to expand at will, hiring young faculty members with fresh ideas. Nor can they dismiss unproductive tenured professors to make way for newcomers. Instead, they have to wait for professors to leave of their own volition.

This process was slowed by federal legislation that outlawed mandatory retirement in 1993. Essentially, tenure moved from guaranteeing employment until age 70 to guaranteeing employment for life. "I'm not sure higher education has thought through the long-term consequences of this," says Dartmouth's dean of faculty James Wright. "Senior faculty, no matter how good they are, need to be replaced by younger people who provide energy and vitality to our institution." Last year four Dartmouth professors retired; meanwhile, nine were given tenure, three had their tenure review period extended, and two were denied tenure. Dartmouth offers an incentive package, designed in the 1970s, to encourage professors to consider early retirement, but has yet to institute any new plan in light of the new law. As it is, the administration expects 30 percent of the tenured faculty to retire over the next eight years.

Dartmouth happens to be better off than most colleges. It can, for the moment, continue bringing new people on board, even as older professors stick around. Several years ago the school announced plans to increase the number of tenured faculty by five percent, adding 15 new positions. This was contingent on raising enough endowment money in the current capital campaign to fund the new slots—which the school has done. "It's terribly important to keep the ratio of tenured faculty to students high," says Wright, who was concerned that while Dartmouth's student body had grown by 35 percent in the 1970s, the faculty had expanded by only 20 percent. The slack was picked up by parttime professors, with no possibility of ever getting tenure. The number of courses taught by this group has remained constant at around 25 percent for the last decade.

Nationally, though, about 40 percent of college professors are parttimers, twice as many as there were 20 years ago. This group often receives no benefits, has zero job security, and, if tenure is indeed the prime guarantor of academic freedom, has none of that either. "Whether it's positive or not, it's undermining tenure," says Richard Lyman, former president of Stanford. "It reflects the fact that universities are trying to deal with one of the basic problems of tenure, which is the inability to create new positions as needs change."

While there has been no formal change in the tenure policy at most schools, the existence of a large, permanently untenured workforce is prompting a re-examination of the system as a whole. Recognizing this, the Pew Charitable Trusts funded a two-year study of tenure-related issues. Says Maryland's Chait, who is collaborating on the study with Judith Gappa, a professor of educational administration at Purdue, "Our goal is not to destroy tenure, but to enlarge the inventory of choices that are available to individuals and institutions." The study examines alternatives to tenure, such as long-term contracts, reduced workloads, and more frequent sabbaticals. And any abridgement to tenure would almost surely drive up professorial salaries. As Dartmouth economics professor Jack Menge points out, "The captains of industry don't get tenure, but they get a salary of $10 million to cover their risk."

The study will also address some of the problems of women in higher education. While men make up 67 percent of tenure-track faculty, the cadre of underpaid academic temps is equally weighted between the sexes. One reason is that women have only recently moved into academia, and a lot of tenured positions are filled by middle-aged and older men. Women hold just 22.6 percent of tenured positions nationwide. At Dartmouth, the figure is slightly better-26 percent, the highest in the Ivy League. Gappa thinks those numbers reflect the inequities of a system that was created when the workforce was primarily male. The grueling probationary period the years during which a professor's work is scrutinized—often coincides with the age at which women bear and raise children. Some women—and men—simply opt out of tenure and all the associated benefits and prestige. One alternative would be to stop the tenure clock so parents can take a few years out to raise children. Dartmouth already has such a program. An assistant professor can add one year per child to the probationary period.

Tenure may be particularly vulnerable to an overhaul today because academic freedom is taken for granted, and so the original argument for tenure seems less compelling. Within academia, it is still often professed that tenure is essential to ensure intellectual freedom. And yet the whole enterprise operates smoothly and freely under circumstances in which one third of its participants lack tenure.

The fact is, today it can be hard to fire employees for cause, let alone for expressing their opinions. "A professor used to say something that wasn't popular with wealthy established people and he was in the soup," says Frank Newman, president of the Education Commission of the States and former president of the University of Rhode Island. "But essentially today all employees in any profession have protection against that kind of treatment. We've shifted a long way from the days when tenure was essential to protect people."

Jay Parini, a professor of English at Middlebury College, agrees: "The Constitution protects free speech just fine. And far from promoting free speech, tenure encourages people to stay silent, especially junior faculty. If I were more timid I think I'd have tenure at Dartmouth." In 1981 Parini was denied tenure at Dartmouth, in large part, he believes, because he had recently published a novel that lampooned the school. "I've always said what I think and the problem is that what I thought when I was 27 or 28 was not very mature," says Parini. "The situation should be that young intellectuals can throw ideas around and be a little bit crazy. Original and good ideas often come out of bad ideas."

There is disagreement about the extent to which junior faculty at Dartmouth feel free to be "a little bit crazy." 'You go to these big faculty meetings and you can always tell the junior faculty because they're the nervous ones, always grinning," says Victor Leo Walker II, assistant professor of drama. "They sometimes don't want to rock the boat."

But very few junior professors, including Walker, will admit to keeping silent. "Of course tenure is political; what in this life isn't? But I don't think I've been timid about speaking my mind or doing things that are controversial," says Anneliese Orleck, assistant professor of history. Marty Favor, an assistant professor of English, says, "I'm pretty bold; I go ahead and say what I want. In fact, they are probably risking very little. By speaking out, scholars get noticed. "There's a perception you have to toe the line, but in our department, those who have been outspoken are at least as likely, if not more likely, to get tenure," says economist Menge. Sam Abel '79, assistant professor of drama, agrees. "My gut feeling is that it's not the risk takers who get booted out. You've got to put yourself a little bit on the line to make a name for yourself." Abel's forthcoming book, Opera in the Flesh, should help him do that. The book, says Abel, contends that opera's impact is erotic more than intellectual. "If someone doesn't raise an eyebrow, there wasn't much point in writing it," he says.

Of course, this begs the question of what constitutes taking a risk: if writing a book that raises eyebrows helps the case for tenure, is it really risky at all? Or, taking it one step further, isn't it possible that desire to get tenure might actually inspire eyebrow-raising work at the expense of less flashy scholarship? The ways in which pre-tenure anxiety—at least temporarily—stifles creativity are probably far more subtle. Faculty members frequently mention being inhibited teachers during the pre-tenure years. "Feeling like you're working on sufferance is not an emancipatory experience," says the history department's Darrow. "I feel much more free since I got tenure to try different kinds of teaching—to work with small groups, to give different types of assignments. You often see people blossom after tenure."

Teaching is an unusually critical component of the tenure decision at Dartmouth. In addition to a review of a candidate s professional writings, scores of letters from former students are solicited and considered. The impolitic publication of his novel aside, Parini concedes that he "hadn't found his voice as a teacher" while he was at Dartmouth. Parini, whose books were—and continue to be—highly praised, thinks he only became a good teacher after he left. "Tenure is a very cruel system," says Parini. "It puts this artificial six- or seven-year window on people during which time they have to become a fabulous teacher and a fabulous and well-known scholar. That's unrealistic. It's very hard to develop evenly as a teacher and a scholar."

Susan Ackerman agrees. She says the problem with tenure decisions "is that they can sometimes be unnecessarily rigid and final. Schools might think that offering tenure to a promising but unproven professor is too risky: If the promise never pans out, they will be stuck with a lackluster professor for 35 years."

Many people, including Ackerman, are intrigued by a system of long-term contracts, whereby after two initial three-year terms, strong faculty members are given ten years to immerse themselves in ambitious research projects—but are reviewed again after the decade is up. It would give the College a chance to hang on to promising scholars who might not have hit their stride, without making a lifetime commitment.

But there are plenty of drawbacks to ten-year contracts. "That isn't always long enough to complete significant research," says Jane Lipson, associate professor of chemistry. Carol Folt, associate professor of biology, agrees. "If you have contracts and judge people on how much money they bring in and how many papers they write," says Folt, "they'd never branch out, which is fundamental to science."

Others think ten-year contracts would leave a school open to intellectual trendiness. One of the virtues of tenure is that administrators can't jump on every bandwagon, hiring ten Keynesian economists one decade and replacing them with ten supply-siders the next. Tenure ensures continuity. "I'm glad that if something like classics is going to be downsized, it's going to be a slow-motion process, geared to someone retiring," says Jere Daniell '55, professor of history. "A place like Dartmouth ought to have a classics department."

There is also the argument that a system of ten-year contracts would change the very character of the institution that scholars, bound to a school more or less for life, build, shape, and strengthen it. "I think of tenure as the process by which young colleagues are brought m," says Wright. "After a number of years, some of them are invited into partnership in the same way young people are invited into partnership in a law firm. Having faculty assume the responsibility of partners is absolutely critical. If faculty didn't fully share in responsibility for Dartmouth, it would be a much weaker place."

What the tenure issue comes down to, then, is nothing less than a debate over the nature of academia. Are professors employees or partners? Should the university respond more to the needs of the outside world, or keep it at arm's length? On the one hand, there is the traditional model of the university: a self-governing community of scholars pursuing the life of the mind to the ultimate benefit of society, but not at its behest. At the other extreme, there is what Bollinger calls the what have you done for me lately, free-market paradigm. Departments come and go, depending on student demand; professors are periodically evaluated, and rewarded or dismissed, just like employees in any other profession.

Many decisionmakers are starting to agitate for this second model. John Immerwahr, chairman of the philosophy department at Villanova University, has surveyed leaders—politicians, CEOs, nonprofit presidents—on the issues confronting higher education. Most of them have taught at universities, served on their boards, or, at the very least, played tennis with the local college president. Among this group, Immerwahr has found nearly universal contempt for tenure. "Leaders think this society has been restructured and downsized in a severe way," says Immerwahr. "And while they might not have lost their jobs themselves, they might have had to fire 25 other people. Still, they think their organization operates better and they look at universities and say, 'You've shaken up your food service and administration, but your structure has been unchanged since 1250.' They wouldn't mind so much, but the universities come to them asking for money and complaining about their problems."

In the face of such criticism, when the biggest concern in higher education is money, the best argument for tenure may be that it exempts people who are devoting their lives to thought from having to constantly prove their worth. The problem with a university that reviews its scholars too often is that it discourages ambitious, risky intellectual endeavors. Says Bollinger, "Its time frame is too short for what it is the academic community is supposed to do, which is think new thoughts and transmit them to students and the broader society." Innovative experiments that may ultimately lead to a cure for AIDS don't always show results on a strict schedule; groundbreaking books can take decades to write. "Great ideas don't come out of a pressured atmosphere, but out of a much more protected atmosphere," says James Freedman. "When you give faculty members tenure at age 35, what you're saying is: 'We have great faith in your promise and are committed to giving you the rest of your life to develop that promise without feeling you have to respond to the fads of the moment.'"

Flawed though it may be, expensive, inefficient, and unfair, for the moment tenure is the only reason this protection happens.

"I DON'T KNOW WHY THE PROFESSORIATE SHOULD HAVE THIS SPECIAL ROLE IN THIS BLOODY SOCIETY." CHUCK BRAUN, PROFESSOR OF CHEMISTRY

"YOU CAN ALWAYS TELL THE JUNIOR FACULTY BECAUSE THEY'RE THE NERVOUS ONES, ALWAYS GRINNING," VICTOR LEO WALKER 11, ASSISTANT PROFESSOR OF DRAMA

"MY GUT FEELING IS THAT IT'S NOT THE RISK TAKERS WHO ARE BOOTED OUT." SAM ABEL '79, ASSISTANT PROFESSOR OF DRAMA

"SCHOOLS MIGHT THINK OFFERING TENURE TO A PROMISING BUT UNPROVEN PROFESSOR IS TOO RISKY." SUSAN ACKERMAN '80, ASSISTANT PROFESSOR OF RELIGION

"YOU OFTEN SEEPEOPLE BLOSSOMAFTER TENURE." MARGARET DARROW, ASSOCIATE PROFESSOR OF HISTORY

"I'M GLAD THAT IF SOMETHING LIKE CLASSICS IS GOING TO BE DOWNSIZED, IT'S GOING TO BE A SLOW MOTION PROCESS," JERE DANIELL '55, PROFESSOR OF HISTORY

"No description of private property has been regarded as more sacred than college livings. They are the estates and freeholds of a most deserving class of men; of scholars who have consented to forego the advantages of professional and public employments, and to devote themselves to science and literature, and the instruction of youth, in the quiet retreats of academic life."

Winter JENNIFER'REESE lives in San Francisco, California.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

Feature“Who the Hell is Lucifer?”

June 1996 By Brenda Gross ’79 -

Feature

FeatureNoble Boots

June 1996 By Chris Clarke ’75 -

Feature

FeatureAMEN! TO THE GOSPEL CHOIR

June 1996 By Suzanne Leonard ’96 -

Article

ArticleUnderground Reading

June 1996 By Kathleen Burge ’89 -

Article

ArticleOffice Hours

June 1996 By Noel Perrin -

Article

ArticleThe First Four-Minute Mile and the Last Coverup?

June 1996 By “E. Wheelock”

Features

-

Feature

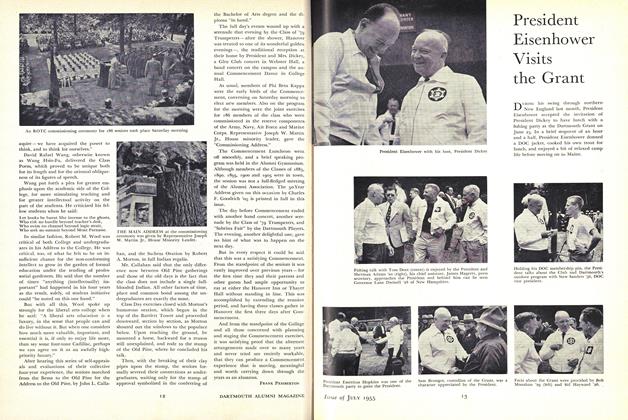

FeaturePresident Eisenhower Visits the Grant

July 1955 -

Feature

FeatureGOOD HAIR

MAY | JUNE 2014 By Ana Sofia De Brito ’12 -

Feature

Feature30,000 Dartmouth Men Are Her Friendsand Problems

December 1961 By CLIFFORD L. JORDAN '45 -

Cover Story

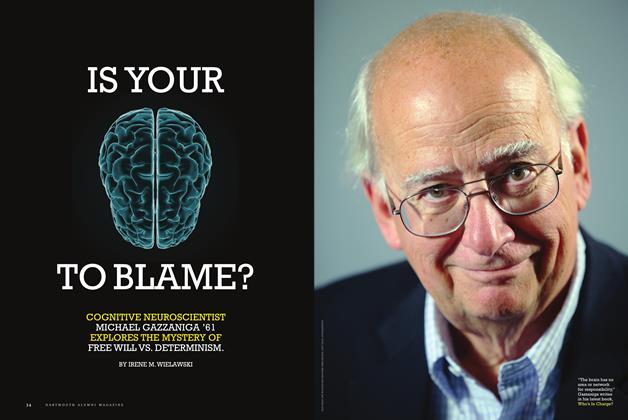

Cover StoryIs Your Brain to Blame?

Nov - Dec By Irene M. Wielawski -

Feature

FeatureSteady State

September 1976 By Pierre Kirch -

Feature

FeatureThe Humanistic Pursuit of Values

MAY 1967 By ROBIN J. SCROGGS