Keith Boykin '87 has a first book out. It is very, very different from what Bill Clinton once thought it was.

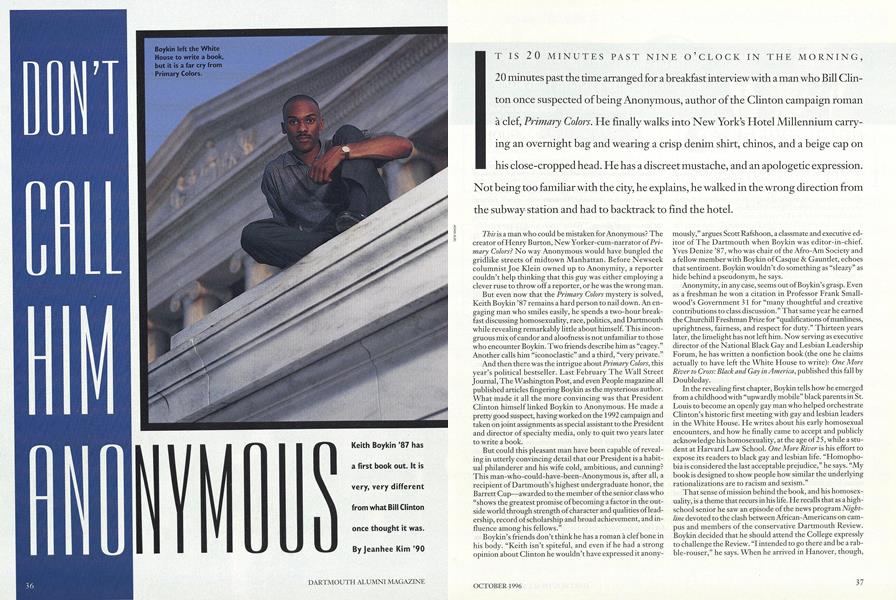

IT IS 20 MINUTES PAST NINE O'CLOCK IN THE MORNING, 20 minutes past the time arranged for a breakfast interview with a man who Bill Clinton once suspected of being Anonymous, author of the Clinton campaign roman a clef, Primary Colors. He finally walks into New York's Hotel Millennium carrying an overnight bag and wearing a crisp denim shirt, chinos, and a beige cap on his close-cropped head. He has a discreet mustache, and an apologetic expression. Not being too familiar with the city, he explains, he walked in the wrong direction from the subway station and had to backtrack to find the hotel.

This is a man who could be mistaken for Anonymous? The creator of Henry Burton, New Yorker-cum-narrator of Primary Colors? No way Anonymous would have bungled the gridlike streets of midtown Manhattan. Before Newseek columnist Joe Klein owned up to Anonymity, a reporter couldn't help thinking that this guy was either employing a clever ruse to throw off a reporter, or he was the wrong man.

But even now that the Primary Colors mystery is solved, Keith Boykin '87 remains a hard person to nail down. An engaging man who smiles easily, he spends a two-hour breakfast discussing homosexuality, race, politics, and Dartmouth while revealing remarkably little about himself. This incongruous mix of candor and aloofness is not unfamiliar to those who encounter Boykin. Two friends describe him as "cagey." Another calls him "iconoclastic" and a third, "very private."

And then there was the intrigue about Primary Colors, this year's political bestseller. Last February The Wall Street Journal, The Washington Post, and even People magazine all published articles fingering Boykin as the mysterious author. What made it all the more convincing was that President Clinton himself linked Boykin to Anonymous. He made a pretty good suspect, having worked on the 1992 campaign and taken on joint assignments as special assistant to the President and director of specialty media, only to quit two years later to write a book.

But could this pleasant man have been capable of revealing in utterly convincing detail that our President is a habitual philanderer and his wife cold, ambitious, and cunning? This man-who-could-have-been-Anonymous is, after all, a recipient of Dartmouth's highest undergraduate honor, the Barrett Cup—awarded to the member of the senior class who "shows the greatest promise of becoming a factor in the outside world through strength of character and qualities of leadership, record of scholarship and broad achievement, and influence among his fellows."

Boykin's friends don't think he has a roman a clef bone in his body. "Keith isn't spiteful, and even if he had a strong opinion about Clinton he wouldn't have expressed it anonymously," argues Scott Rafshoon, a classmate and executive editor of The Dartmouth when Boykin was editor-in-chief. Yves Denize '87, who was chair of the Afro-Am Society and a fellow member with Boykin of Casque & Gauntlet, echoes that sentiment. Boykin wouldn't do something as "sleazy" as hide behind a pseudonym, he says.

Anonymity, in any case, seems out of Boykin's grasp. Even as a freshman he won a citation in Professor Frank Smallwood's Government 31 for "many thoughtful and creative contributions to class discussion." That same year he earned the Churchill Freshman Prize for "qualifications of manliness, uprightness, fairness, and respect for duty." Thirteen years later, the limelight has not left him. Now serving as executive director of the National Black Gay and Lesbian Leadership Forum, he has written a nonfiction book (the one he claims actually to have left the White House to write): One MoreRiver to Cross: Black and Gay in America, published this fall by Doubleday.

In the revealing first chapter, Boykin tells how he emerged from a childhood with "upwardly mobile" black parents in St. Louis to become an openly gay man who helped orchestrate Clinton's historic first meeting with gay and lesbian leaders in the White House. He writes about his early homosexual encounters, and how he finally came to accept and publicly acknowledge his homosexuality, at the age of 25,while a student at Harvard Law School. One More River is his effort to expose its readers to black gay and lesbian life. "Homophobia is considered the last acceptable prejudice," he says. "My book is designed to show people how similar the underlying rationalizations are to racism and sexism."

That sense of mission behind the book, and his homosexuality, is a theme that recurs in his life. He recalls that as a highschool senior he saw an episode of the news program Nightline devoted to the clash between African-Americans on campus and members of the conservative Dartmouth Review. Boykin decided that he should attend the College expressly to challenge the Review. "I intended to go there and be a rabble-rouser," he says. When he arrived in Hanover, though, he found the paper "declining in influence." Instead of rabble-rousing, Boykin says with a touch of irony, "I joined the establishment as editor-in-chief of The Dartmouth."

At a time when the College was grappling with the ethics of its investments in apartheid South Africa, and while the faculty was publicly expressing its dissatisfaction with its president, the editorials under Boykin's directorate struck many as a voice of reason. After members of the Dartmouth Community for Divestment erected shanties on the Green, The D called for their dismantling: "The focus of the diversity issue at Dartmouth has shifted from the College's holdings in South Africa to the use of shanties as a form of protest," said the lead editorial. When Review staffers dubbed themselves the Committee to Beautify the Green and took sledgehammers to the shantiescausing President David McLaughlin' 54 to call a moratorium on classes—the editors wrote: "The campus turmoil is indicative of a more profound malaise." The editorial listed as examples an anti-gay, beer-throwing incident on fraternity row, the debate over the Indian symbol, and McLaughlin's absence from campus on Martin Luther King Day.

"What I say about The D during those years is that it shed more light than heat," says Alex Huppe, then the director of Dartmouth's News Service and now Harvard University's public affairs director. In true journalistic fashion, says Huppe, the paper did not show a discernible political bent, nor did its editor. "If the paper had been truly politicized during that time, the people would have been far more confused."

While Boykin credits Dartmouth with having an enormous influence on his activism, few would have guessed it at the time. "I thought he was possibly apolitical," says Huppe. It seems that only after dropping the mantle of objectivity as editor-in-chief did Boykin let loose his passions. At Harvard Law he was one of 11 students who filed a lawsuit against the university for discrimination against hiring women and minorities in tenure-track positions. "Keith was a person who, as editor of The D, was criticized by the left for failing to engage in the fight, and then, at Harvard, suddenly he's leading the protests," muses Andy Fields '89, who knew Boykin at Dartmouth and graduated in the same class at Harvard Law. While the protest brought national attention to the issue, it fell short of the activists' goals. A district judge threw out the lawsuit; and, according to Harvard Law School spokesman Michael Chmura, minorities now represent nine percent of the law school's tenure-track professors—just one percent more than in 1991.

"Unfortunately," says Boykin, "the administration has a bigadvantage in conflicts with students, and that's staying power."

He himself is not about to quit the field. The accolades he received while an undergraduate clearly imparted a sense of public obligation, one that he talks about freely. The Churchill Freshman Prize comes with a set of books that carry an inscription he takes seriously: "Honesty with oneself, fairness towards others, sensitivity to duty and courage in its performance, these qualities make manhood and on manhood rests the structure of society." While others would be grateful for the recognition, Boykin also perceives the award as a call to public service. He can recite statements on integrity and public service from turn-of-the-century Dartmouth president William Jewett Tucker 1861. Boykin also feels a great responsibility as a recipient of the Barrett Cup. He took to heart the award's recognition of his "promise of becoming a factor in the outside world." "Everything I've done since college has in part been an effort to live up to that expectation," he says.

One of his proudest contributions to the Clinton administration was the letter he ghostwrote for the President in 1993, which was read to participants in the largest gay rights march on Washington. It reads, in part: "In this great country, founded on the principle that all people are created equal, we must learn to put aside what divides us and focus on what we share." Though gay-rights activists criticized the letter as bland, its tone is mindful of the President's delicate position. "Not only does Keith have innate intelligence and a strong work ethic, but he knows how to put out small fires and even big ones with diplomacy. That's probably helped him more than anything," says Boykin's best friend and track teammate, Andy Hart '87.

That nuanced approach might help in what Boykin hopes will be a national debate on black gay issues. He is currently touting One More River on tour. And though he plans to stay at the Leadership Forum for a few more years, he talks about getting involved in education, maybe on a national level. He has some experience with the subject, having taught public school in DeKalb County, Georgia, some years ago. Whatever he ends up doing, expect it to include public service, and some public attention.

So was Boykin, pre-Joe Klein, a logical choice for capital-A Anonymous? We 11... On the acknowledgments page for OneMore River to Cross, he does thank Chris Georges, the Wall Street Journal reporter who linked Boykin to Primary Colors, for being the "unofficial publicist for my first book."

But Keith Boykin anonymous? Never.

Boykin left the White House to write a book,but it is a far cry from Primary Colors.

Keith and Hill and Bill, 1995

BOYKIM BECAME AN OPENLY GAY WAN WHO HELPED ORCHESTRATE CLINTON'S HISTORIC FIRST MEEING WITH GAY AND LESBIAN LEADERS. Keith and Hill and Bill, 1995

Jeanhee Kim is a reporter for Money magazine.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThis Man Is an Island

October 1996 By ROBERT SULLIVAN '75 -

Feature

FeatureNaming the Animals

October 1996 By Robert Pack '51 -

Cover Story

Cover StorySecond Nature

October 1996 By Jay Heinrichs -

Feature

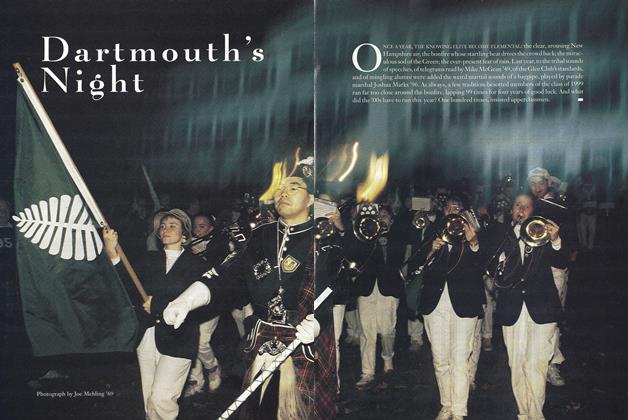

FeatureDartmouth's Night

October 1996 -

Article

ArticleKnowing Your Place

October 1996 By Jim Collins'84 -

Article

ArticleThe Orange on Campus Is Not on Leaves

October 1996 By "E. Wheelock"

Features

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryOUTING CLUB PIN

MARCH | APRIL 2014 -

Cover Story

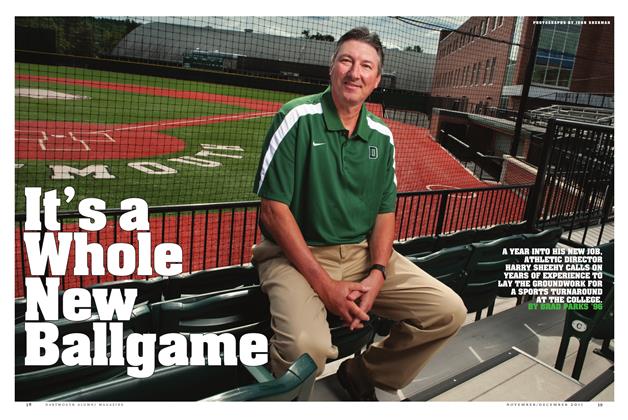

Cover StoryIt’s a Whole New Ballgame

Nov/Dec 2011 By BRAD PARKS ’96 -

Feature

FeatureValedictory to the College

JULY 1966 By MICHAEL DAVID DANZIG '66 -

Feature

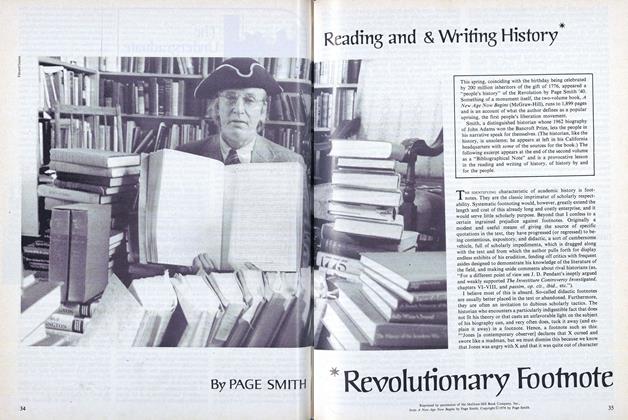

FeatureReading and Writing History and Revolutionary Footnote

May 1976 By PAGE SMITH -

Feature

FeatureAlumni News

July/August 2006 By Rodger Ewy '53, Rodger Ewy '53 -

Feature

FeatureMENAGE A HUIT

October 1976 By ROGERS E. M. WHITAKER