You can ride the bus or at least read the book.

When Jack Kerouac's rambling novel Onthe Road was published in 1957, it quickly came to define a generation. Kerouac gave an early voice to the Beat Movement as he described alienated young people hitchhiking across the country, searching for truth in poverty, drugs, sex, and new experiences.

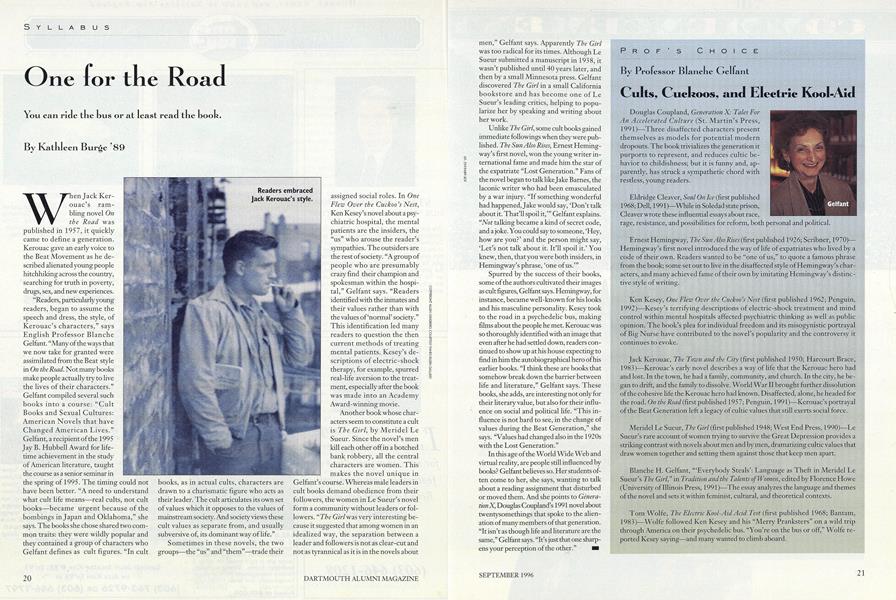

"Readers, particularlyyoung readers, began to assume the speech and dress, the style, of Kerouac's characters," says English Professor Blanche Gelfant. "Many of the ways that we now take for granted were assimilated from the Beat style in On the Road. Not many books make people actually try to live the lives of their characters." Gelfant compiled several such books into a course: "Cult Books and Sexual Cultures: American Novels that have Changed American Lives." Gelfant, a recipient of the 1995 Jay B.Hubbell Award for life time achievement in the study of American literature, taught the course as a senior seminar in the spring of 1995. The timing could not have been better. "A need to understand what cult life means real cults, not cult books became urgent because of the bombings in Japan and Oklahoma," she says. The books she chose shared two common traits: they were wildly popular and they contained a group of characters who Gelfant defines as cult figures. "In cult books, as in actual cults, characters are drawn to a charismatic figure who acts as their leader. The cult articulates its own set of values which it opposes to the values of mainstream society. And society views these cult values as separate from, and usually subversive of, its dominant way of life."

Sometimes in these novels, the two groups the "us" and "them" trade their assigned social roles. In OneFlew Over the Cuckoo's Nest, Ken Kesey's novel about a psychiatric hospital, the mental patients are the insiders,the "us" who arouse the reader's sympathies. The outsiders are the rest of society. "A group of people who are presumably crazy find their champion and spokesman within the hospital," Gelfant says. "Readers identified with the inmates and their values rather than with the values of'normal' society." This identification led many readers to question the then current methods of treating mental patients. Kesey's descriptions of electric shock therapy, for example, spurred real life aversion to the treatment, especially after the book was made into an Academy Award-winning movie.

Another book whose characters seem to constitute a cult is The Girl, by Meridel Le Sueur. Since the novel's men kill each other off in a botched bank robbery, all the central characters are women. This makes the novel unique in

Gelfant's course. Whereas male leaders in cult books demand obedience from their followers, the women in Le Sueur's novel form a community without leaders or followers. "The Girlwas very interesting because it suggested that among women in an idealized way, the separation between a leader and followers is not as clear cut and not as tyrannical as it is in the novels about men," Gelfant says. Apparently The Girl was too radical for its times. Although Le Sueur submitted a manuscript in 1938, it wasn't published until 40 years later, and then by a small Minnesota press. Gelfant discovered The Girl in a small California bookstore and has become one of Le Sueur's leading critics, helping to popularize her by speaking and writing about her work.

Unlike The Girl, some cult books gained immediate followings when they were published. The Sun Also Rises, Ernest Hemingway's first novel, won the young writer international fame and made him the star of the expatriate "Lost Generation." Fans of the novel began to talk like Jake Barnes, the laconic writer who had been emasculated by a war injury. "If something wonderful had happened, Jake would say, 'Don't talk about it. That'll spoil it,'" Gelfant explains. "Not talking became a kind of secret code, and a joke. You could say to someone, 'Hey, how are you?' and the person might say, 'Let's not talk about it. It'll spoil it.' You knew, then, that you were both insiders, in Hemingway's phrase, 'one of us.'"

Spurred by the success of their books, some of the authors cultivated their images as cult figures, Gelfant says. Hemingway, for instance, became well-known for his looks and his masculine personality. Kesey took to the road in a psychedelic bus, making films about the people he met. Kerouac was so thoroughly identified with an image that even after he had settled down, readers continued to show up at his house expecting to find in him the autobiographical hero of his earlier books. "I think these are books that somehow break down the barrier between life and literature," Gelfant says. These books, she adds, are interesting not only for their literary value, but also for their influence on social and political life. "This influence is not hard to see, in the change of values during the Beat Generation," she says. "Values had changed also in the 1920s with the Lost Generation."

In this age of the World Wide Web and virtual reality, are people still influenced by books? Gelfant believes so. Her students often come to her, she says, wanting to talk about a reading assignment that disturbed or moved them. And she points to Generation, Douglas Coupland's 1991 novel about twentysomethings that spoke to the alienation of many members of that generation. "It isn't as though life and literature are the same," Gelfant says."It's just that one sharpens your perception of the other."

Readers embraced Jack Kerouac's style.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe Language of Innocence

September 1996 By KATE COHEN '92 -

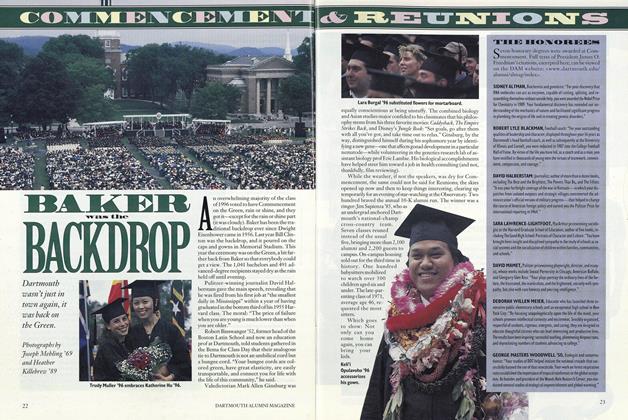

Cover Story

Cover StoryBAKER WAS THE BACKDROP

September 1996 -

Feature

FeatureStaying Clear

September 1996 By Jeanet Hardigg Irwin '80 -

Feature

FeaturePassion

September 1996 By Fiona Bayly '89 -

Feature

FeatureConfidence

September 1996 By Paid Tsongas '62 -

Feature

FeatureFaith

September 1996 By Seward, "Pat" Brewster '50

Kathleen Burge '89

-

Article

ArticleWhat Beethoven Heard

NOVEMBER 1996 By Kathleen Burge '89 -

Article

ArticleGender and Power in Shakespeare

OCTOBER 1997 By Kathleen Burge '89 -

Article

ArticleMedieval Road Trips

JANUARY 1998 By Kathleen Burge '89 -

Article

ArticleNovels that Came in from the Cold

APRIL 1998 By Kathleen Burge '89 -

Article

ArticleThe Origin of Endangered Species

SEPTEMBER 1998 By Kathleen Burge '89 -

Article

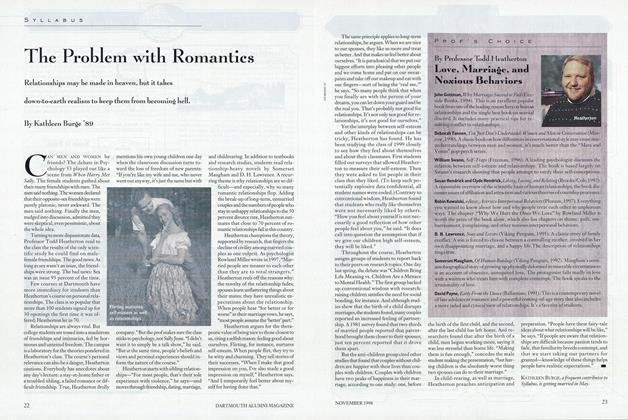

ArticleThe Problem with Romantics

NOVEMBER 1998 By Kathleen Burge '89

Article

-

Article

ArticleFollowing the resignation of Ernest Martins Hopkins

November, 1910 -

Article

ArticleWHITEMAN'S ORCHESTRA ENLIVENS ALL HANOVER

January, 1926 -

Article

ArticleSports Results

June 1940 -

Article

Article1918 SONS IN COLLEGE

March 1948 -

Article

ArticleWITH THE BIG GREEN TEAMS

-

Article

ArticleHanover Browsing

January 1941 By HERBERT F. WEST '22