Spy fiction cracked the mystery behind the Red Scare.

LURED TO THE CENTRAL Intelligence Agency in the heady aftermath of the Cuban missile crisis, David Lindgren has worked there intermittently since 1964. This is what he can say about his work: He was an analyst. He worked for the directorate of intelligence. He specialized in satellite imagery. Period. Is he implying that he was a spy? "The CIA never uses the word 'spy,'" is all he will say. After a slightly more detailed description of his job no, he won't elaborate slipped into an advertisement for a Dartmouth tour of Russia he once led, Lindgren was called into the headquarters of the agency's security office and "questioned."

Lindgren can speak more openly about his other life, that of a geography professor. But when it comes to teaching a freshman seminar called "The Spying Game: The Myth and Reality of Cold War Espionage," he has to leave his CIA experiences at the classroom door. Instead, he uses fictional accounts—spy novels—to help chart the murky decades between 1945 and 1991.

In the shrouded world of espionage, novels offered a rare peek into the spying game. Despite American prominence in the Cold War, British writers John Le Carre, Frederick Forsythe, Len Deighton, Graham Greene, lan Fleming—dominated the spy novel genre. Even American readers lagged behind the British. James Bond aside, Lindgren argues, the genre tends to be too slowmoving for American tastes. "The novels are very cerebral. They are often based on well-developed characters and so they tend to be high on character development and low on action. Much of the action is only implied. If there is violence, it's typically in the passive sense."

Lindgren sees spy novels as snapshots that document the course of the Cold War, including shifts in Western attitudes toward the Soviet Union. In the beginning of the Cold War, when little information about the Soviet Union leaked out from behind the Iron Curtain, Western countries held exaggerated notions of Soviet military capabilities. When the Soviets launched Sputnik Americans were terrified that Soviet leaders could also launch intercontinental ballistic missiles. The spy novels of that era painted Soviet villains in a gruesome light. "The 1950s and lan Fleming reflect that period when we feared the Soviets and made them into larger-than-life monsters," Lindgren says. "The good guys were very good and the bad guys were horrible. The Soviets in Fleming's novels are often demented. Their physical characteristics are grotesque."

By the 1960s Kennedy and Khrushchev had met, and each side began to form a somewhat more realistic image of the other. In The Spy Who Came in From the Cold, Lindgren's own favorite spy novel, Le Carre's character development wasn't so black and white. Both the British and Eastern Bloc spies possessed good and bad qualities. By the 1980s Greene and Tom Clancy were painting more even-handed accounts of the Soviets.

For all their escapist feats and fast-paced action, says Lindgren, even Fleming's novels bear some historic value. They offer clues to the British mindset during the early days of the Cold War. When Fleming began writing in the 1950s, the British Secret Service, now known as M16, had egg on its face from the defection of highly placed Soviet agents within its ranks, including the so-called Cambridge Five. The CIA had surpassed the Brits' own organization as the predominant intelligence force. But in his novels Fleming created a world where the image of the British Secret Service had never been tarnished. James Bond was the dashing model of spydom, while his CIA counterpart often played a secondary role. "That was the England that many people by the 1950s and '6os longed for," Lindgren says. "The days when the British had a great empire arid when they, not the United States, were the major military power."

Lindgren also assigns his students nonfiction reading about the Cold War, such as The Spy Who Saved the World, an account of Soviet Colonel Oleg Penkovsky, who fed information to the Americans until he was executed by the KGB. Then Lindgren asks students to give the spy novels a reality check. Excluding Fleming's books, both Lindgren and his students find that, despite an occasional scene that strains the fabric of credibility, the novels weren't a bad portrayal of how intelligence forces work. And for good reason. Most of the best-known authors worked for intelligence agencies before they turned to writing. One exception is Clancy, author of The Hunt for Red October and other thrillers. An expert in naval history, Clancy is self-taught about intelligence-gathering and so knowledgeable that the CIA has asked him to lecture.

Lindgren's one caveat about the accuracy of spy novels lies in their emphasis. The books tend to focus on secret agents whose jobs, while exciting, account for a fraction of real intelligence work. "Unfortunately, most of the work that intelligence agencies engage in would not be the stuff of good movies," Lindgren notes. "It's largely people reading reports, translating intercepted communications, and analyzing satellite imagery. It provides nice context you see Clancy's Jack Ryan going into CIA headquarters but clearly there's not enough action."

The collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 and the end of the Cold War created an obvioous problem for spy novelists. The enemy had disappeared. Writers have already begun the daunting task of appointing the next global enemy—the Mafia, the Irish Republican Army, drug lords, terrorists. But Lindgren argues that the new novels are not as gripping as the Cold War tales that built on the collective fears of their readers. "The spy novel seemed to work best when we knew little about the Russians and the threat of nuclear war was very real," he say. "Now it's the end of the twentieth century and the spy novel, at least for now, has apparently exhausted itself."

It is, he laments, the end of a genre.

James Bond is still the world's most famous spy.

Writer KATHLEEN BuRGE unravels mysteries from her home base in Norwich, Vermont.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe Trembling Edge Of Science

April 1998 By Karen Endicott -

Feature

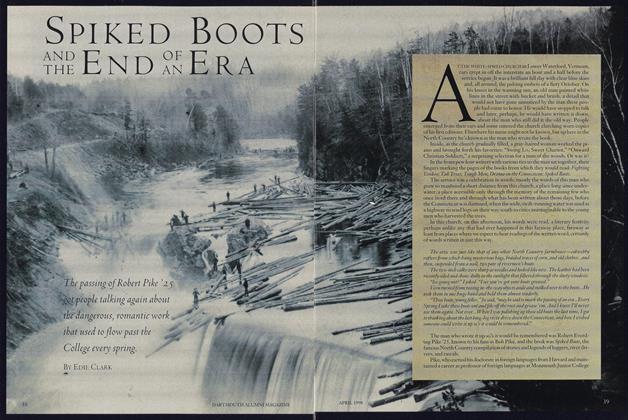

FeatureSpiked Boots and the End of an Era

April 1998 By Edie Clark -

Feature

FeatureA Change in the Weather

April 1998 -

Feature

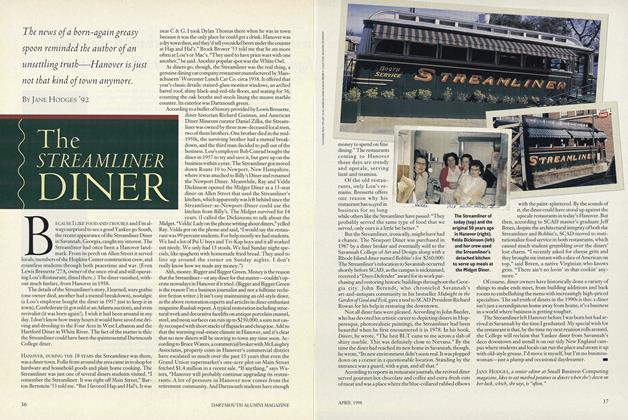

FeatureThe STREAMLINER DINER

April 1998 By Jane Hodges '92 -

Article

ArticleThe Benefits of a College Town

April 1998 By Jeanhee Kim '90 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1985

April 1998 By John MacManus

Kathleen Burge '89

-

Article

ArticleGender and Power in Shakespeare

OCTOBER 1997 By Kathleen Burge '89 -

Article

ArticleThe Origin of Endangered Species

SEPTEMBER 1998 By Kathleen Burge '89 -

Article

ArticleThe Problem with Romantics

NOVEMBER 1998 By Kathleen Burge '89 -

Article

ArticleTales from Uncle Anton

JANUARY 1999 By Kathleen Burge '89 -

Article

ArticleCAREER CHANGERS

MAY 1999 By Kathleen Burge '89 -

Article

ArticleMother Russia's Daughters

DECEMBER 1999 By Kathleen Burge '89

Article

-

Article

ArticleR. M. LEACH '02 CANDIDATE FOR LIEUTENANT-GOVERNOR OF MASS.

FEBRUARY, 1928 -

Article

ArticleVisitor of the Month

November 1943 -

Article

ArticleUndocked

Sept/Oct 2010 -

Article

ArticleMILESTONES

DECEMBER 1930 By Craig Thorn, Jr. -

Article

ArticleA Dorm Experiment

JUNE 1963 By DAVID R. BOLDT '63 -

Article

ArticleMedical School

JANUARY 1969 By HARRY W. SAVAGE M '27