The Bard, tetter than most historians, captured the lives of his era's women.

HERE'S A SNAPSHOT from English history. In 1611 Margaret Knowesley confided to friends that the local priest had tried to seduce her. When word of her accusation got out, the priest charged her with slander. Knowesley was found guilty and sentenced to three successive Saturdays of public punishment, beginning with a two-hour whipping.

Here's a snapshot from Shakespeare's comedy Measure for Measure, first performed less than a decade earlier. Antonio, a smooth- talking deputy to the Duke, promises Isabel that he will save her brother from the death sentence imposed upon him—if she will sleep with Antonio. When Isabel refuses and threatens to expose the cunning politician, he retorts:

Who will believe thee, Isabel?My unsoiled name, th' austereness of my life,My vouch against you, and my placei' the state,Will so your accusation overweighThat you shall stifle in your own report,And smell of calumny.

Things eventually work out better for Isabel than they did for Margaret Knowesley. That's because Shakespeare was writing a comedy, says Lynda Boose, an English professor and Shakespeare scholar who teaches a course called "Gender and Shakespeare." Reality was much harsher. The Knowlesley case, says Boose, who researched it in England, typifies the mind-set of seventeenth-century England—and offers insight into why Shakespeare's Antonio expects to violate the law with impunity.

Boose is one of many scholars studying Shakespeare anew to see how Renaissance ideas about women play out in his work. (Most scholars assume the Shakespeare canon was written by a man. Shakespeare's wife Anne, though, is sometimes mentioned as die true Bard, but that's another story.) Shakespeare's works, according to Boose, can fill some of the gaps left by standard, male-oriented histories of that era. Those histories record few of the details of women's lives.

"The focus of much new work on Shakespeare and other Renaissance drama is what I would call socio-cultural," Boose explains. "Rather than just assuming the language and plot of a Shakespearean drama as a given and analyzing it within the restricted framework of the play, 'post-structuralist' critics are interested in embedding the play within the culture that produced it. Late sixteenth-century England was a monarchy based on patriarchy, hierarchy, and a nearly obsessive concern for order. But it was also a world in which new Protestant sects were springing up on a daily basis, fast displacing Catholicism. A queen sitting on top of the whole structure inverted the paradigm in every possible way, and 40 years into the seventeenth century, the monarch was overthrown and executed by a civilian army. The focus of contemporary critics is on just how Shakespeare's plays figure into this conflicting world."

Many of the gender details in Shakespeare's works reflect real rather than imagined historical practices and beliefs. For example, in several of the plays, women liken their wedding sheets to death, as

when Juliet declares, "My sheet should be my shroud." Says Boose, "When you've got these strongly used and reused metaphors, then maybe you should suspect them of being something besides a metaphor." Indeed, historians have confirmed that Elizabethan women were buried in their wedding sheets.

Sometimes the historical practices lurk just outside Shakespeare's lines. For example, in the final scene of The Taming of theShrew, Kate acquiesces to Petruchio and urges women everywhere to recognize their husbands' rightful dominance. Women are bound to "serve, love and obey," Kate says, prostrating herself on the floor and slipping her hand beneath Petruchio's foot. The words and the gesture, Boose says, ternate explanation involving volcanic eruptions. And then all headlines broke loose. Or as Drake wryly observed on these pages, "In retrospect the uproar becomes less surprising. It involved dinosaurs, outer space, and mystery. It had everything going for it but rape, incest, and the royal family."

Gubbio, Italy, was the site for academia's ultimate away game. It was thought that iridium dug from the location might advance one theory over the other. For a while it looked like the Alvarez side was on

top. (The work of some young researchers from Dartmouth, the bastion of the volcano theory, actually supported the meteor theory.)

That didn't seem to matter to Drake. While his theory- may have been eclipsed, the other team still lacked crucial evidence. At a small gathering at Norwich's Monshire Museum of Science a few years ago, Drake and Dartmouth earth science professor Joel Blum laid out the parameters of the debate. That evening, Drake was more than a renowned scientist. He probed the weak points of the meteorite theory with facts, wit, and charm. This was science. This was fun.

The latest extinction theory says that a speeding object from space smashed into the face of the earth, causing volcanic eruptions on the opposite side. Does this mean that the Dino War ended in a draw? An academic version of a negotiated settlement? In The New York Times obituary for Drake, Officer said his colleague had never bought into the new theory. That seemed in keeping with Drake's character.

Closing his interview with our reporter, Drake mused, "Some things we'll never know. I think we might never have an elegant agreement on what killed the dinosaurs. That's okay. Mysteries are fun."

Portia understoodbetter than most menthe art of the deal.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

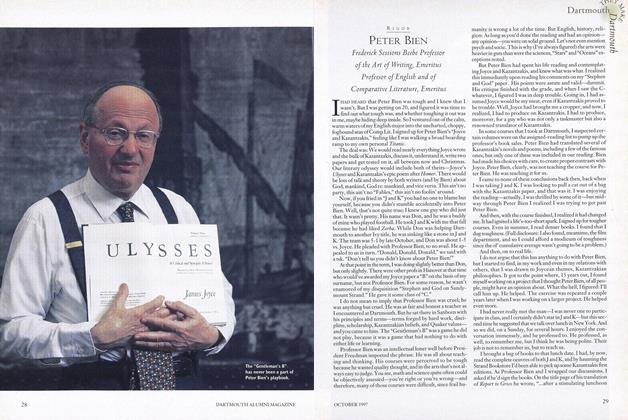

Cover StoryPeter Bien

October 1997 By Robert Sullivan '75 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryM. Lee Pelton

October 1997 By Jane Hodges '92 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryMarysa Navarro-Aranguren

October 1997 By Holly Sorensen '86 -

Cover Story

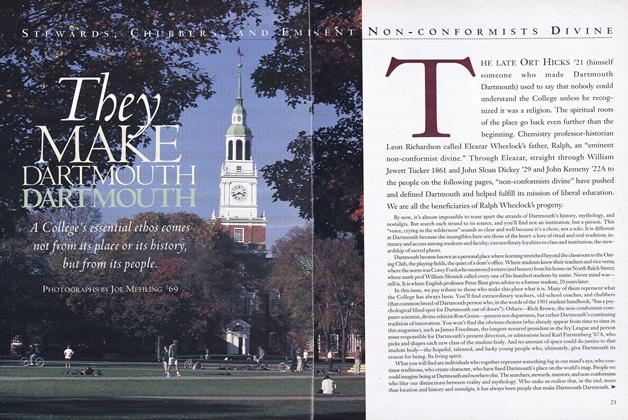

Cover StoryThey Make Dartmouth Dartmouth

October 1997 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryWilliam Cook

October 1997 By Heather McCutchen '87 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryChris Miller '97

October 1997 By Jake Tapper ’91

Kathleen Burge '89

-

Article

ArticleShades of Black

Novembr 1995 By Kathleen Burge '89 -

Article

ArticleOne for the Road

SEPTEMBER 1996 By Kathleen Burge '89 -

Article

ArticleNovels that Came in from the Cold

APRIL 1998 By Kathleen Burge '89 -

Article

ArticleThe Origin of Endangered Species

SEPTEMBER 1998 By Kathleen Burge '89 -

Article

ArticleTales from Uncle Anton

JANUARY 1999 By Kathleen Burge '89 -

Article

ArticleMother Russia's Daughters

DECEMBER 1999 By Kathleen Burge '89