Why animal rights rhetoric may be wrong.

It seemed like a fledgling Congressional staffer's dream: Writing a landmark bill to save the elephants. It was the 19705, and Gail Osherenko renko was just out of law school. She spent two years drafting an elephant protection act; Congress passed a law banning trade in ivory.

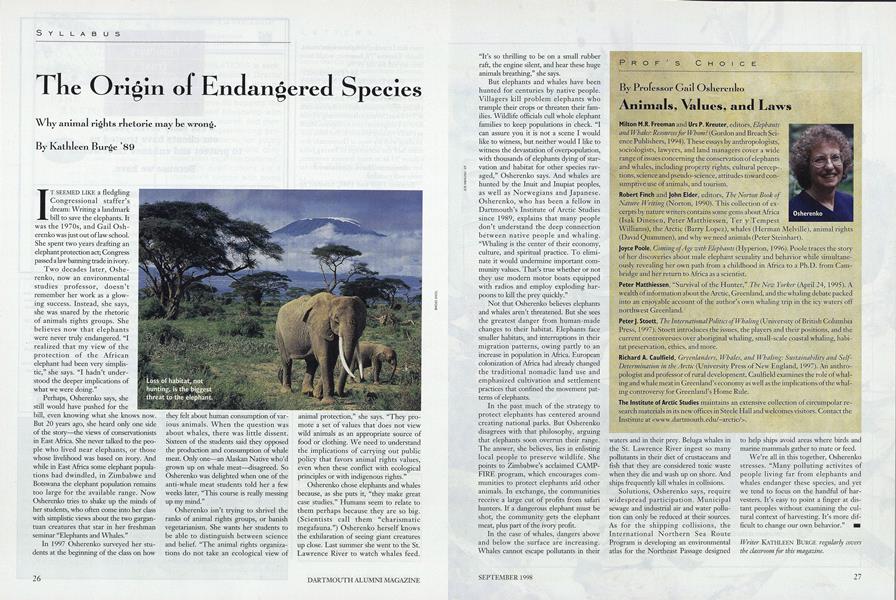

Two decades later, Osherenko, now an environmental studies professor, doesn't remember her work as a glowing success. Instead, she says, she was snared by the rhetoric of animals sights groups. She believes now that elephants were never truly endangered. "I realized that my view of the protection of the African elephant had been very simplistic," she says. "I hadn't understood the deeper implications of what we were doing."

Perhaps, Osherenko says, she still would have pushed for the bill, even knowing what she knows now. But 20 years ago, she heard only one side of the story the views of conservationists in East Africa. She never talked to the people who lived near elephants, or those whose livelihood was based on ivory. And while in East Africa some elephant populations had dwindled, in Zimbabwe and Botswana the elephant population remains too large for the available range. Now Osherenko tries to shake up the minds of her students, who often come into her class with simplistic views about the two gargan- tuan creatures that star in her freshman seminar "Elephants and Whales."

In 1997 Osherenko surveyed her students at the beginning of the class on how they felt about human consumption of various animals. When the question was about whales, there was little dissent. Sixteen of the students said they opposed the production and consumption of whale meat. Only one an Alaskan Native who'd grown up on whale meat disagreed. So Osherenko was delighted when one of the anti-whale meat students told her a few weeks later, "This course is really messing up my mind."

Osherenko isn't trying to shrivel the ranks of animal rights groups, or banish vegetarianism. She wants her students to be able to distinguish between science and belief. "The animal rights organizations do not take an ecological view of animal protection," she says. "They promote a set of values that does not view wild animals as an appropriate source of food or clothing. We need to understand the implications of carrying out public policy that favors animal rights values, even when these conflict with ecological principles or with indigenous rights."

Osherenko chose elephants and whales because, as she puts it, "they make great case studies." Humans seem to relate to them perhaps because they are so big. (Scientists call them "charismatic megafauna.") Osherenko herself knows the exhilaration of seeing giant creatures up close. Last summer she went to the St. Lawrence River to watch whales feed. "It's so thrilling to be on a small rubber raft, the engine silent, and hear these huge animals breathing," she says.

But elephants and whales have been hunted for centuries by native people. Villagers kill problem elephants who trample their crops or threaten their families. Wildlife officials cull whole elephant families to keep populations in check. "I can assure you it is not a scene I would like to witness, but neither would I like to witness the devastation of overpopulation, with thousands of elephants dying of starvation and habitat for other species ravaged," Osherenko says. And whales are hunted by the Inuit and Inupiat peoples, as well as Norwegians and Japanese. Osherenko, who has been a fellow in Dartmouth's Institute of Arctic Studies since 1989, explains that many people don't understand the deep connection between native people and whaling. "Whaling is the center of their economy, culture, and spiritual practice. To eliminate it would undermine important community values. That's true whether or not they use modern motor boats equipped with radios and employ exploding harpoons to kill the prey quickly."

Not that Osherenko believes elephants and whales aren't threatened. But she sees the greatest danger from human-made changes to their habitat. Elephants face smaller habitats, and interruptions in their migration patterns, owing partly to an increase in population in Africa. European colonization of Africa had already changed the traditional nomadic land use and emphasized cultivation and settlement practices that confined the movement patterns of elephants.

In the past much of the strategy to protect elephants has centered around creating national parks. But Osherenko disagrees with that philosophy, arguing that elephants soon overrun their range. The answer, she believes, lies in enlisting local people to preserve wildlife. She points to Zimbabwe's acclaimed CAMPFIRE program, which encourages communities to protect elephants arid other animals. In exchange, the communities receive a large cut of profits from safari hunters. If a dangerous elephant must be shot, the community gets the elephant meat, plus part of the ivory profit.

In the case of whales, dangers above and below the surface are increasing. Whales cannot escape pollutants in their waters and in their prey. Beluga whales in the St. Lawrence River ingest so many pollutants in their diet of crustaceans and fish that they are considered toxic waste when they die and wash up on shore. And ships frequently kill whales in collisions.

Solutions, Osherenko says, require widespread participation. Municipal sewage and industrial air and water pollution can only be reduced at their sources. As for the shipping collisions, the International Northern Sea Route Program is developing an environmental atlas for the Northeast Passage designed to help ships avoid areas where birds and marine mammals gather to mate or feed.

We're all in this together, Osherenko stresses. "Many polluting activites of people living far from elephants and whales endanger these species, and yet we tend to focus on the handful of harvesters. It's easy to point a finger at distant peoples without examining the cultural context of harvesting. It's more difficult to change our own behavior."

Loss of habitat, not hunting, is the biggest threat to the elephant.

Writer KATHLEEN BURGE regularly covers the classroom for this magazine.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

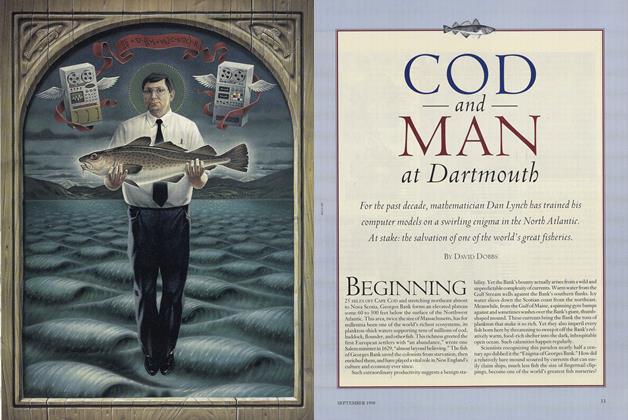

FeatureCOD and MAN at Dartmouth

September 1998 By David Dobbs -

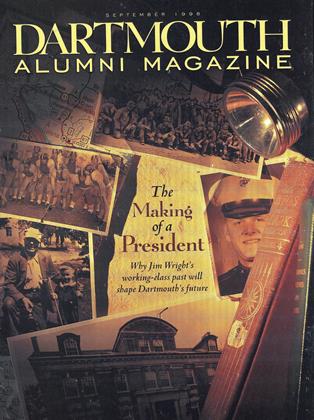

Cover Story

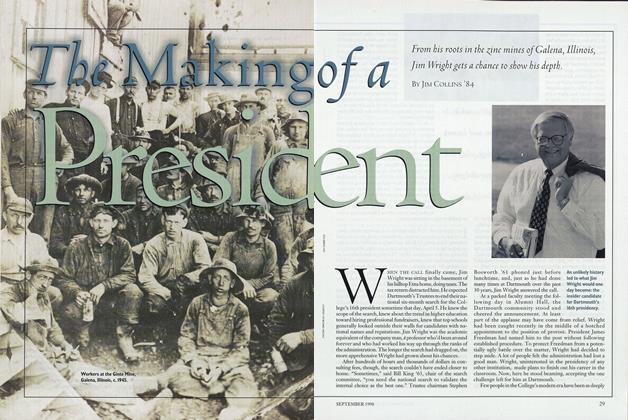

Cover StoryThe Making of a President

September 1998 By Jim Collins '84 -

Feature

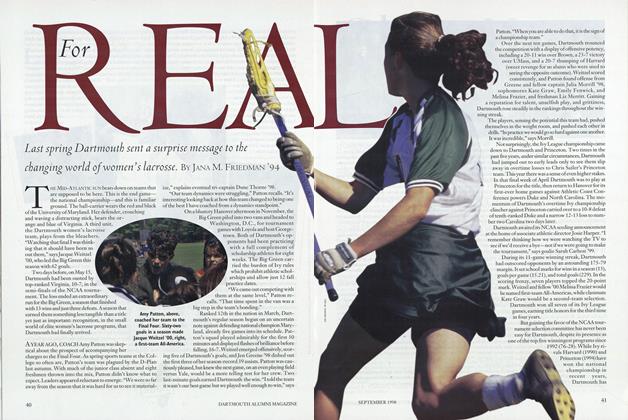

FeatureFOR REAL

September 1998 By Jana M. Friedman '94 -

Feature

FeatureFrom Rap to Ritual

September 1998 By Everett Wood '38 -

Article

ArticleFour Aces

September 1998 By Noel Perrin -

Article

ArticleA Soggy Commencement

September 1998

Kathleen Burge '89

-

Article

ArticleShades of Black

Novembr 1995 By Kathleen Burge '89 -

Article

ArticleGender and Power in Shakespeare

OCTOBER 1997 By Kathleen Burge '89 -

Article

ArticleGender and Power in Shakespeare

OCTOBER 1997 By Kathleen Burge '89 -

Article

ArticleNovels that Came in from the Cold

APRIL 1998 By Kathleen Burge '89 -

Article

ArticleTales from Uncle Anton

JANUARY 1999 By Kathleen Burge '89 -

Article

ArticleMother Russia's Daughters

DECEMBER 1999 By Kathleen Burge '89