A newly discovered bamboo manuscript adds a fresh twist to an ancient literary whodunit.

There was something formed out of chaos, That was born before Heaven and Earth. Quiet and still! Pure and deep! It stands on its own and doesn't change. It can be regarded as the mother of Heaven and Earth. I do not yet know its name: I "style" it "the Way." —From the Tao "teching, translated by Robert Henricks

IT WAS ONE OF THE STRING OF DAYS last May when the weather seemed to fast-forward to late July, and" a sudden Coney Island of lounging bodies and airborne frisbees had materialized on the Dartmouth Green. Across the street in Alumni Hall, however, a different sort of fever had taken hold. Thirty-five scholars had been given first crack at a new body of evidence on an ancient Chinese mystery: the origin of the Tao teching.

Known variously as the Book of Lao-tzu, Laozi, or Lao-tse, "the book of the way and its virtue" consists of 81 poem-like chapters between four and 24 lines in length. The work has been translated more than any text besides the Bible, including more than a hundred English versions. In China it has been read or memorized by every educated person through the centuries and has profoundly influenced the country's culture and history. "Chinese civilization and the Chinese character would have been utterly different if the [Tao teching] had never been written," wrote Chinese scholar and Dartmouth professor Wing-Tsit Chan in the introduction to his still-revered 1963 translation. "No one can hope to understand Chinese government, culture, art, medicine, and even cooking without a real appreciation of the profound philosophy taught in this little book." Yet nobody knows who wrote this hugely influential text, or when.

Hence the stir archeologists recently created when they found a significantly older version of the text than any previously known. Might this version bring scholars closer to a definitive picture of how the Tao teching came to be? That was the hope of the conference. Scholars met by day in intense sessions and sat up late at night in their rooms analyzing the materials, "drawing all kinds of trees," says Sarah Allan, a professor of Chinese studies at Dartmouth who, along with religion professor Robert Henricks, organized the conference. As one participant remarked, "It's like we found an original version of Plato."

The comparison to Plato is apt in more than one respect. While Athenian Greece was enjoying its golden age of literature and philosophy, China was in the midst of a comparable ascendancy. This occurred after the Chou Empire, founded in about 1100 B.C. by an alliance of tribes, began to weaken in the eighth century B.C. Five centuries of interstate warfare and intrastate skulduggery led to the Chou Empire's dissolution in 222 B.C. Henricks likens the upheavals to Shakespeare's blood-soaked royal tragedies, with "sons plotting against mothers, mothers killing sons. It was the worst sort of deception and it was all for power, all for control." All this fighting and back-stabbing was extremely good for philosophy. Each of these smaller kingdoms needed philosophers to advise them on such matters as uniting the empire, winning battles, and surviving adversity. Many philosophies competed. Most didn't last.

Two that survived were Confucianism, based on the Analects of the philosopher Confucius (551-479 B.C.), and Taoism, based on the Tao teching. Through the centuries, Taoism has played a sort of beatnik to the pinstriped patrician of Confucianism. While the latter instructs that the good life is based on good government, which in turn depends on disciplined, learned individuals who respect the social hierarchy and understand their place within it, the Tao te ching bids the reader to observe nature, retreat from society, and not bother striving for rank, power, scholarship, and material comforts. Such efforts are at odds, it says, with the "Tao," or true nature, with which all people, things, places, and events are imbued and which we must accept in order to live happy, healthy lives.

Throughout the ages the two philosophies have complemented each other in everyday Chinese life, says Allan. "Government and social life was Confucian, but the other side of life, having to do with the individual, was found in Taoist philosophy." It was normal for members of the ruling class to practice Confucianism while in office and, upon retirement, take up Taoism.

Beyond Asia, however, it's the Tao teching that has most caught the popular imagination. A lead article in the influential Utne Reader (a sort of Reader's Digest for baby-boomers) put the Tao teching second on a list tided "The Loose Canon: 150 Great Works to Set Your Imagination on Fire." The word "Tao" has entered our vocabulary as a synonym for "essence"—as in the titles of two perennially popular books, The Tao of Physics by Fritjof Capra and The Tao of Pooh by Benjamin Hoff. still cited on college students' web pages as among the books which have affected students most.

Henricks himself has found the Tao te ching personally relevant. As a graduate student who thought he hated research and was pursuing his doctorate only so he could teach, Henricks was struck by a passage which states that the wise person (as he later translated it) "puts self-concern out of his mind; yet finds that his self-concern is preserved. Is it not because he has no self-interest, that he is therefore able to realize his self-interest?"

"By die time I was done with graduate school," Henricks says, "I had discovered I was in love with research, that I was a solitary person who loves libraries and likes looking at things that no one else is looking at. By putting aside my self-interest, I actually had preserved my self-interest. What this passage says to me is that we don't always know ourselves. We only come to gain self-knowledge by doing something we don't want to do. It's these sort of paradoxical things that make me love the book."

And yet the question has remained. Who wrote this cross-culturally prized work? Many Chinese including those at the Dartmouth conference—believe the traditional account that the text was written in the sixth century B.C. by someone known as Lao-tzu (meaning "old master,"), said to have been an archivist for the Chou imperial court. Leaving the empire's capital upon retirement, he was persuaded by a gatekeeper whom he passed to record his views on life, resulting in the legendary manuscript. In Chinese art Lao-tzu is often shown making that journey, riding a water buffalo, an open robe revealing the sage's ample belly.

To most Western scholars, however—including many at the Dartmouth conference—Lao-tzu is no more real than that other big-bellied icon, Santa Claus. They believe that the Tao te ching was the work of several authors at several intervals, well after Lao-tzu was supposed to have lived.

Until now there was no physical evidence to support either view. The oldest known version of the Tao te ching, discovered in 1973 in a tomb in south central China, dated from the middle of the second century B.C. Then in 1993, in a tomb near the central Chinese city of Guodian, a cache of some 800 bamboo slips was exhumed and found to include a version of the Tao te ching. (Such slips, threaded together side by side like bamboo blinds, were the predominant storage medium for writing in ancient China and, scholars surmise, the reason Chinese writing is vertical rather than horizontal.) Judging from the period the tomb was thought to have been sealed, the text had to date from the fourth century B.C. or earlier.

At first, the Chinese government kept quiet about the discovery, to give its archeologists time to conserve the slips, figure out the order in which they belonged, and prepare a modern Chinese transcription. But word got around. Whispers about the text reached Henricks and Allan, who attended a Taoism conference in Beijing in the summer of 1995, where the government made a brief official report on the Guodian find. Before long the two had used their reputations and connections to arrange an international conference at Dartmouth to coincide with the Chinese government's publication of photos of the conserved bamboo slips alongside a modern Chinese transcription.

The group they convened at Dartmouth was about half Chinese and half Westerners and represented the diverse types of expertise needed to mine information from an ancient Chinese text. In addition to experts in ancient Chinese history, literature, and philosophy were the archeologists who excavated the site. They confirmed that, although the tomb had been robbed before the excavation, the bamboo slips appeared not to have been disturbed. Also present were experts on the history of the development of Chinese characters what particular characters meant and how they sounded. Such knowledge is critical to the interpretation of ancient Chinese texts, says Henricks. because the texts used many "loan words." Scribes sometimes substituted for one character a different character with a different meaning but the same sound, such as we might write, "I like a good imported bier" and mean the beverage, not the final resting place.

At what was perhaps the first academic conference in America ever to be conducted solely in Chinese, the scholars speculated on a range of issues that might have bearing on the Guodian text's interpretation, including the possible social status and occupation of the tomb's occupant. Some theorized—based in part on a lacquer bowl found in the tomb that seemed to be inscribed to a teacher that he could have been the tutor of some member of the upper aristocracy. The central absorbing issue, however, besides the manuscript's age, was that the Guodian Tao te ching contains material from only 32 of the 81 chapters that appear in the Tao te ching as we know it—and in a totally different order. What's more, in the same bundle of slips and written in the same handwriting are slips containing a text not previously known but apparently Taoist in nature.

What did the scholars make of all this? "I think it is safe to say—though we didn't ask for a show of hands that our group was divided on this issue pretty well along East and West lines," Henricks says. "Many of our colleagues from China remain convinced that the book of Lao-tzu was indeed composed around 500 B.C. by the individual who goes by that name." This hypothesis sees the Guodian text as excerpts from and commentary on that complete text. Others, however, feel the Guodian text was a sort of proto Tao te ching, perhaps one of many, Henricks says. "A lany of us in the West feel the Guodian text is convincing evidence that the Lao-tzu was not in existence circa 300 B.C., and that it was compiled by one or a number of editors from sources such as these."

The proof of a successful conference, however, is not resolution but more conferences. Subsequent panels on the Guodian text have already been held, and more are coming. Allan. Henricks. and the scholars from China with whom they planned the Dartmouth conference intend to hold another in the not-too-distant future, most likely at Beijing University.

Meanwhile Henricks is at work on an English translation of the Guodian Tao te ching. As for Allan, among her projects is an ambitious effort to find funding to help the Chinese government excavate the rest of the cemetery at Guodian. Given that one tomb yielded ancient texts that were still intact, there are likely to be others. Chinese government archeologists are so busy trying to keep up with burial sites elsewhere that are being; destroyed by development and dams, says Allan, that the Guodian site has low priority.

The ancient mystery of the Tao te ching, for now, remains unsolved. An answer, however, may lie in the text itself. From Chapter 4, translated by Wing-Tsit Chan:

Tao is empty (like a bowl). It may be used, but its capacity is never exhausted,

It is bottomless, perhaps the ancestor of all things. It blunts its sharpness. It unties its tangles. It softens its light. It becomes one with the dusty world. Deep and still, it appears to exist forever. I do not know whose son it is. It seems to have existed before the Lord.

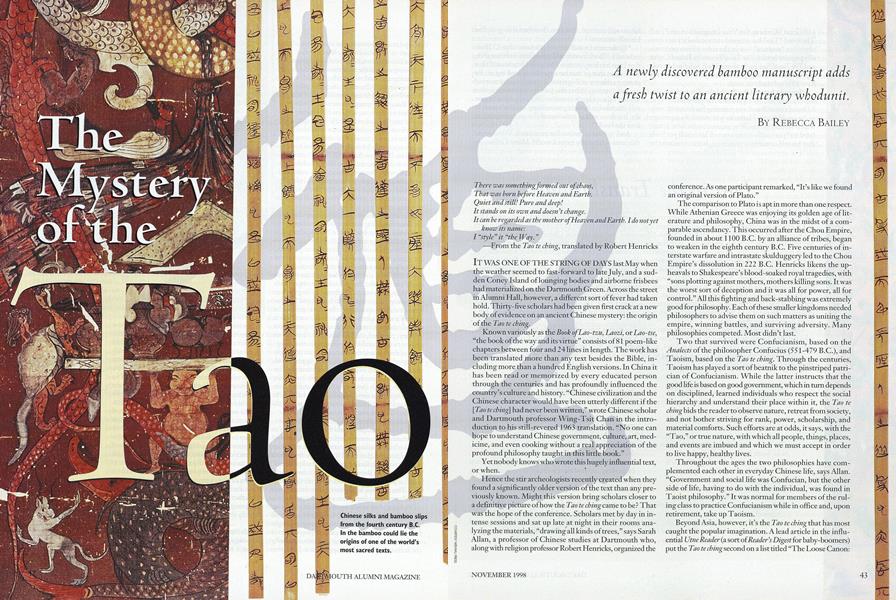

Chinese silks and bamboo slips from the fourth century B.C. In the bamboo could lie the origins of one of the world's most sacred texts.

REBECCA BAILEY lives in South Strafford, Vermont, and, like the unenlightened souls referred to in Chapter 53 of the Tao te ching, "greatly delight[sj in tortuous paths."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

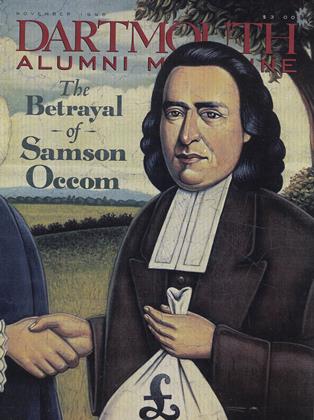

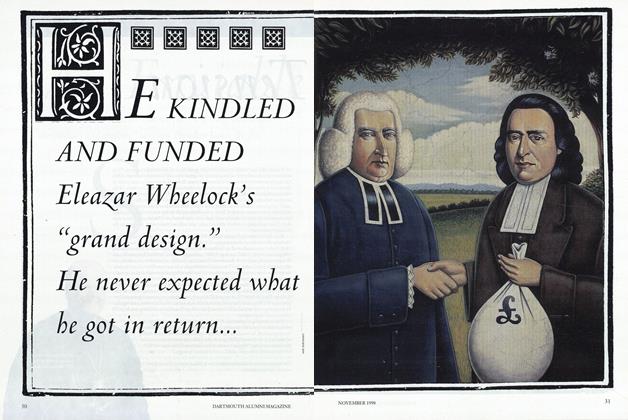

FeatureThe Betrayal Of Samson Occom

November 1998 By Bernd Peyer -

Feature

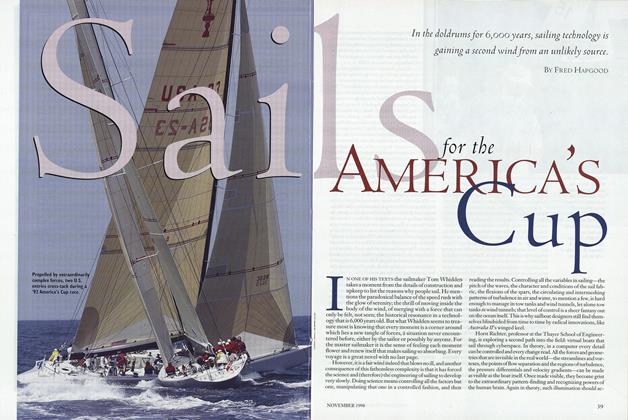

FeatureSails for the America's Cup

November 1998 By Fred Hapgood -

Cover Story

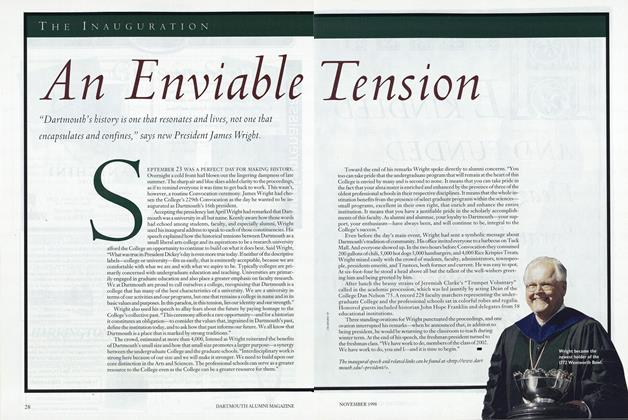

Cover StoryThe Inauguration

November 1998 -

Article

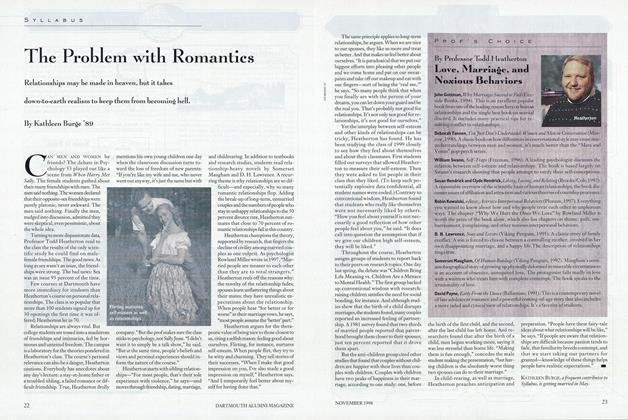

ArticleThe Problem with Romantics

November 1998 By Kathleen Burge '89 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1979

November 1998 By Jeffrey D. Boylan, R. James "Wazoo" Wasz -

Article

ArticleThe Last Adventure

November 1998

Rebecca Bailey

Features

-

Feature

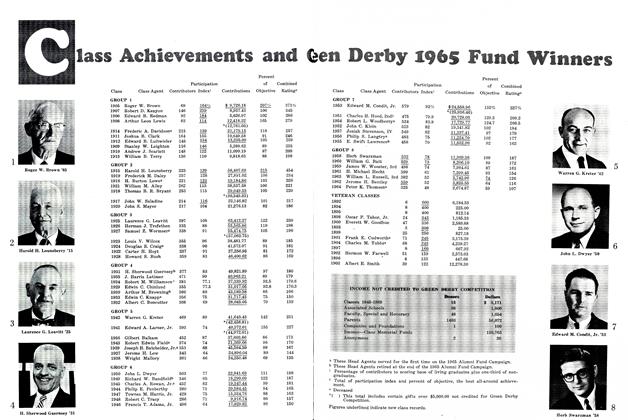

FeatureClass Achievements and Green Derby 1965 Fund Winners

NOVEMBER 1965 -

Feature

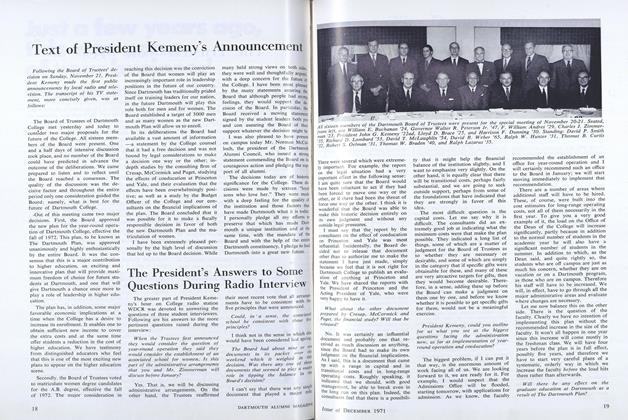

FeatureText of President Kemeny's Announcement

DECEMBER 1971 -

Feature

FeatureOn Being a Full Man

July 1962 By ARTHUR H. DEAN, LL.D. '62 -

Feature

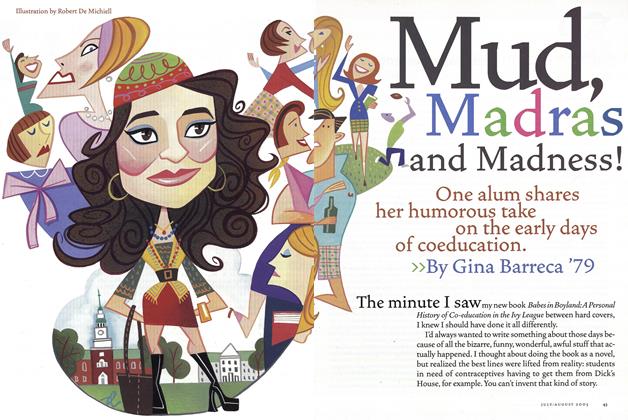

FeatureMud, Madras and Madness!

July/August 2005 By Gina Barreca ’79 -

Feature

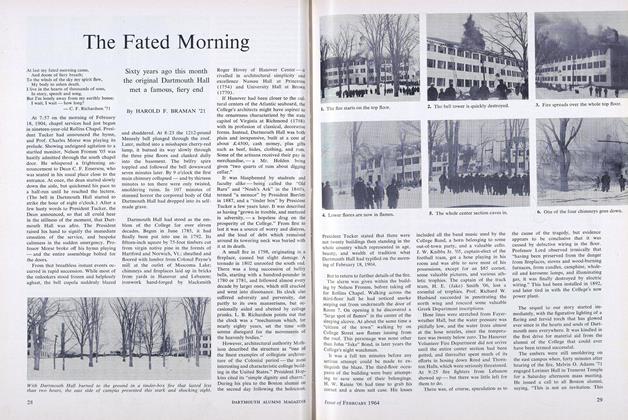

FeatureThe Fated Morning

FEBRUARY 1964 By HAROLD F. BRAMAN '21 -

Feature

FeatureValedictory to 1968

JULY 1968 By PRESIDENT JOHN SLOAN DICKEY